|

Chapter

VI

Of

the Return of Peace — The Troubles of the Commission to Secure the

Release of the Captives Held in Canada — Eunice Refuses to Return —

Visits of Eunice and her Descendants to Their Old Home

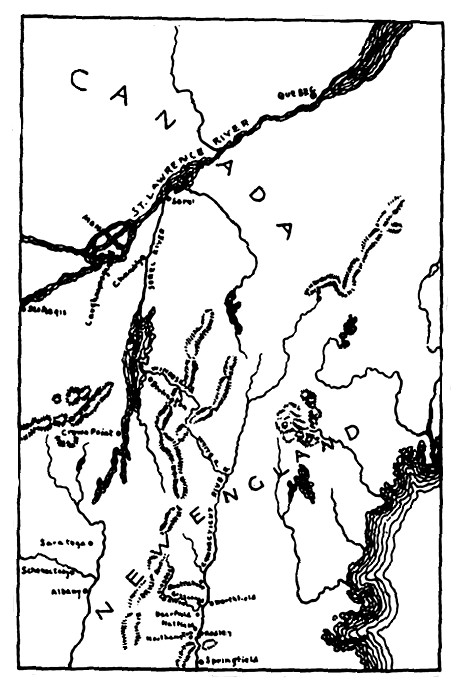

THE same year Schuyler made his Canadian journey peace was established between France and England, and in the autumn orders were received in America for the release of captives. A commission was at once appointed by Governor Dudley of Massachusetts to go to Canada to hunt up and bring home the New England people held there. This commission left Northampton for Albany on the 9th of November, and one of the party was Pastor Williams of Deerfield. The horseback journey to Albany occupied four days. Here winter came, with uncertain weeks of cold and thaws which kept them from proceeding northward till late in December. Then they went on by way of Saratoga and Crown Point, sometimes on snow-shoes, some times in canoes. Thus they reached Chambly, whence they proceeded to Quebec in sleighs. Governor De Vaudrueil gave them his word of honor that all prisoners should have full liberty to return, and told his visitors to go freely among them and send for them to come to their lodgings. The commission were much pleased with their reception, but soon after we find them complaining to the governor that the priests are exerting themselves to prevent the prisoners going. His Excellency replied that he could "as easily alter the course of the waters as prevent the priests' endeavors." Mr. Williams was no less ardent than the priests, and it was presently forbidden that he should have any religious talk with the captives. He was accused of being abroad after eight o'clock in the evening to discourse on religion with some of the English, and he was told that if he repeated the offense he would be confined a prisoner in his lodgings. The priests affirmed that he undid in a moment all they had done in seven years to establish their religion. Early in this Canadian trip Mr. Williams had an interview with his daughter, but she would not leave the Indians; and though he pleaded with them, and with the priests and authorities, some times so much moved that the tears streamed down his face, they simply said that the girl could go or stay as she chose, and she chose to stay. After nine months' absence the commission returned, their efforts largely baffled, and with but twenty-six prisoners. No further attempt was made officially for the redemption of Eunice Williams, but in 1740 another interview was had with her, which led to her thrice revisiting the place of her nativity. She came with her husband and others of the tribe, all in Indian costume, and so entirely had she lost her English that it was only by means of an interpreter that it was possible to carry on the simplest conversation with her. It is said, too, that civilized life was so repugnant to her that she refused to sleep in her relatives' houses. The legend is that while visiting her brother, the minister of Longmeadow, she persisted in staying with the Indians who pitched their camp in the woods east of the parsonage. She was kindly received by her friends, but all inducements held out to get her to stay in her old home were unavailing. The General Court offered a grant of land on condition that she and her husband and children would remain in New England. She refused on the ground that it would endanger her soul.

A company of these Williams Indians visited Deerfield as recently as 1837. There were several families, amounting in all to twenty-three persons. The eldest, a woman of eighty years, affirmed that Eunice was her grandmother. During their stay of a little more than a week they encamped on the village outskirts, and employed their spare time in making baskets. They visited the graves of their ancestors, Rev. John Williams and wife, and attended service on Sunday in an orderly and reverent manner. They refused to receive company on the Sabbath, and at all times and in all respects seemed disposed to conduct themselves decently and inoffensively. Their encampment was frequented by great numbers of persons, almost denying them time to eat their meals, but affording them a ready sale for their baskets. The descendants of Eunice Williams are Indians still, and still have their home on the banks of the St. Lawrence, and they continue to make the baskets and other simple Indian wares of commerce. It is a strange story, and, as I have said before, the mystery still remains as to whether their white ancestress was a savage from choice or lived her long life in repression and unhappiness.   |

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2009

(Return to Web Text-ures)