| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

Chapter

II

Of

King Philip's War Deerfield Destroyed The Settlement Again Begun

Rev. John Williams Becomes the Second Minister Eunice Williams

Is Born, 1696 Her Life as a Child

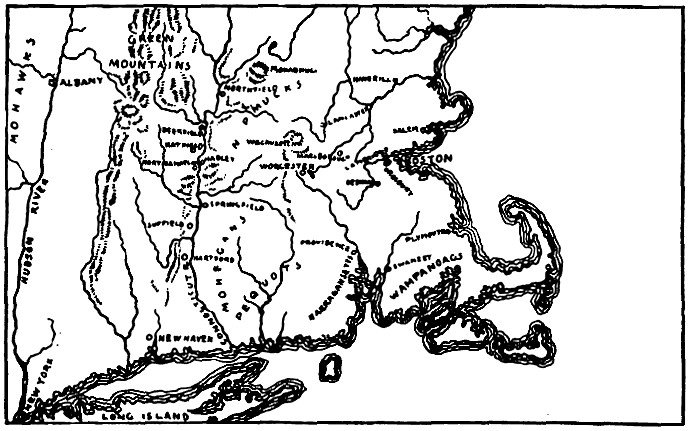

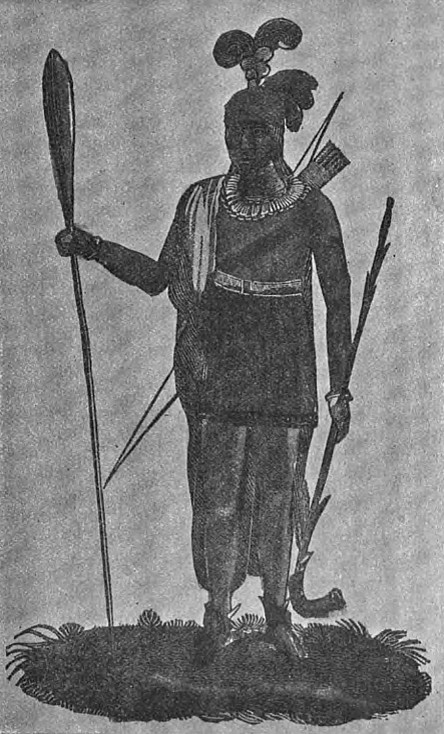

NOW there rose the cloud of wara war of barbarism resisting the encroachments of civilization. It started with Philip, sachem of the Wampanoags, who burned the village of Swanzey and three other villages of Plymouth Colony and murdered many of the inhabitants. By this time the Indians had acquired a good many firearms and become expert in the use of them, so that they were not so unequal a match for the whites as formerly. The Wampanoags were soon put down, but Philip escaped to the Nipmucks of Worcester County, and these savages carried on the war for a year, burning and slaughtering all the way from the Connecticut River, then the western frontier, to within a dozen miles of Boston. In the end, the whites conquered and the greater number of the enemy was killed, while the rest were sold as slaves in the West Indies and elsewhere.  Philip himself was ambushed and shot and the chieftain's hands were shown as a spectacle in Boston, while his ghastly head was set up on a pole in Plymouth, affording the occasion for a public thanksgiving. Scarcely any Indians were left in New England except the friendly Mohegans. The brunt of the savage attacks was borne by the colonies of Massachusetts and Plymouth. Of ninety towns, twelve had been utterly destroyed, while more than forty had been the scene of fire and massacre. More than a thousand men had been slain, and a great many women and children. In the view of the majority of our ancestors, who lived in that day, this devastation had a religious aspect, and the preachers admonished their flocks that these sufferings were directly due to their sins. We find Parson Stoddard of Northampton writing to Increase Mather that "many sins are so grown in fashion that it is a question whether they be sins," and begs him to call the governor's attention to "that intolerable pride in clothes and hair, and the toleration of so many taverns; and suffering home dwellers to be tippling therein." His conclusion is that "it would be a dreadful token of the displeasure of God if these afflictions pass away without much spiritual advantage." Deerfield was one of the sufferers in King Philip's war. It was attacked on September 1st, 1675, several houses were burned and one man killed. After that the inhabitants huddled together in two or three houses, poorly protected by palisades and defended by a handful of soldiers. Many of them piled their household goods on their ox carts and wended their way through the forests to the larger settlements down the river. At Hadley there was a strong garrison which presently began to feel the need of provisions, and in the middle of September, Captain Lathrop with eighty men, besides teamsters and carts, went up to Deerfield to secure the grain which the settlers had there harvested and stacked. It was on their return with the threshed grain that the famous massacre of Bloody Brook occurred, when all but a scant half dozen of the company were slaughtered by the savages.  King Philip From an Old Print Soon after this disaster, the garrison was withdrawn from Deerfield and the Indians burned what was left of the plantation. Several attempts were made to rebuild the village in the following years, but the savages were continually lurking about; more lives were lost, the new buildings were fired, and it was not till 1682 that the settlement was again made permanent. But the enterprise of our wilderness pioneers had been so paralyzed by the reverses and frights of the past that the growth of the hamlet was very slow.  It was six years before they again had a minister. Their choice was John Williams, then but little more than twenty-one years of age. On their part his parishioners agreed to give their minister a home-lot and 220 acres of meadow land. Also, they would build him a house 42 feet long, 20 feet wide, with a lean-to at the rear; would fence his home-lot, and within two years build him a barn and break up his ploughing land. For yearly salary he was to have sixty pounds. This was largely paid in produce, such as wheat, peas, Indian corn and pork.  Soon after his ordination Mr. Williams married a young Northampton woman, and in the next sixteen years there were born to them eleven children. Of these, the sixth child and second daughter was born September 17th, 1696, and was named Eunice, after her mother. She it is who is the subject of this little book. She lived the simple life of the other village children, with its round of work and play, church-going and attending school. She was quick in her studies and became a good reader, and under the double drill at school and home early memorized the catechism. She looked with interest at the tavern when she passed it, half fearfully, for she reflected the home sentiment that it was a place with a decided flavor of ungodliness. Once, in the dusk of a summer evening, she saw two teamsters on the porch, using loud, rude words, and one shook his fist in the other's face, whereat her opinion of the tavern's badness was confirmed, and she ran home in great fright. On the other hand, she liked to loiter at the door of Deacon French's blacksmith shop. That was a place of peace and sobriety, and it was a pleasant sight to see the sparks dance about and hear the metal ring as the Deacon wielded his hammer. The parsonage, with a number of other humble dwellings in the village center, was inclosed by a palisade that included within it about twenty acres. Outside the palisade, the little girl was not allowed to go unless accompanied by one of her elders. But this fence of stout posts with their pointed tops interested her, and she knew the whole line of it, and she often peeked through the chinks of it out into the surrounding woods and clearings. Here and there she could see stockaded dwellings, and she knew that some of her mates in the village school lived in them. It was a strange world, this woodland country outside the palisades. She had heard many stories of the Indians and of the wild creatures of the forest, and she, herself, when walking with her hand in her father's, on the way to make a pastoral call at a house beyond the village defences, had seen three deer feeding in a stumpy clearing.  The Fort-House Near

the northwest angle of the palisaded part of the village stood the

meeting-house, homely and square with a four-sided roof crowned by a

tiny belfry. Close by the church was a heavily-built garrison house

with an overhanging upper story and loopholes from which guns might

be fired. Eunice knew that in case the Indians attacked them and

carried the palisade, it was to this stout fort-house the people

would retreat. She knew how the Indians had burned the town years

before and the stories she heard made her fearful of every shadow

when she stepped outdoors after sun down. Often at bedtime she felt

such fright that she would draw the clothes over her head and catch

her breath at every sound.

|