| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

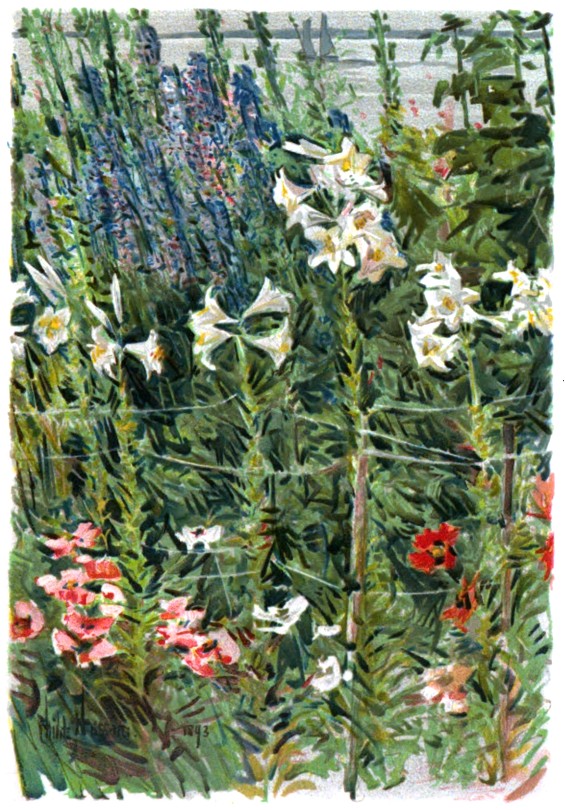

I COPY the notes of a few days' work in the garden in May, just to give an idea of their character and of the variety of occupation in this small space of ground. May 11. This morning at four o'clock the sky was one rich red blush in the east, over a sea as calm as a mirror. How could I wait for the sun to lift its scarlet rim above the dim sea-line (though it rose punctually at forty-seven minutes past four), when my precious flower beds were waiting for me! It was not possible, and I was up and dressed before he had flooded the earth with glory. "Straight was a path of gold for him," I said, as I gazed out at the long line of liquid splendor along the ocean. All the boxes and baskets of the more delicate seedlings were to be put out from my chamber window on flat house-top and balcony, they and the forest of Sweet Peas to be thoroughly watered, and the Pansies half shaded with paper lest the sun should work them woe. At five the household was stirring, there was time to write a letter or two, then came breakfast before six, and by half past six I was out of doors at work in the vast circle of motionless silence, for the sea was too calm for me to hear even its breathing. It was so beautiful, — the dewy quiet, the freshness, the long, still shadows, the matchless, delicate, sweet charm of the newly wakened world. Such a color as the grass had taken on during the last few warm days; and where the early shadows lay long across it, such indescribable richness of tone There was so much for me to do, I hardly knew where to begin. At the east of the house the bed of Pansies set out yesterday was bright with promise, every little plant holding itself gladly erect. I began with the trellis each side of the steps leading down into the garden, and first set out a Cobœa Scandens, one to the right and one to the left, — strong, sturdy plants which I had been keeping weeks in the house till it should be warm enough to trust them out of doors. They were a foot high and stretching their sensitive tendrils in all directions, seeking something for support. They grasped the trellis at once and seemed to spread out every leaf to the warm sun, while I poured cool water and liquid manure about their roots, and congratulated them on their escape into the open ground. Near them, against the same trellis, I put down two Tropæolum Lobbianum Lucifers, a new scarlet variety of these delicate Nasturtiums, that they might climb together over the broad arch. Some time ago I had planted there also some Mexican Morning-glories sent me by an unknown friend, and if they come up, and Cobœa, Nasturtiums, and Morning-glories all climb together and clasp hands with Honeysuckle, Wistaria, and Wild Cucumber, my porch will, indeed, be a bower of beauty! Then against wall and fence I set out the stout bushes of single Dahlias which have been growing ever since last January. A new variety called Star of Lyons interests me. I am anxious to know what it is like, what its color, what its shape. It is such a pleasure always to be finding new varieties and combinations, fresh surprises in unfamiliar flowers. Seeking the smallest posy bed I own, into this I transplanted another stranger, Papaver Alpinum Roseum, a rose-colored Iceland Poppy. How I shall watch it grow, and how eagerly wait for it to blossom! Eight egg-shells full of it were set down and carefully watered. Next, a row of baby Wallflowers were established in a long line near the tall ones that are thick with buds. I am going to try to have a succession of bloom from these, if it can be accomplished, all summer. In another bed I began to set out a few of the choicest Sweet Peas, the new kinds; these were already a foot long from tip to root ends. I have no words to tell what pleasant work this is! After the Sweet Peas were comfortably settled, I covered the whole bed with a length of light mosquito net, pegging it at the corners, laying sticks and stones along the edges to hold it down, so that the saucy sparrows should find no loophole by which to wriggle inside, they having watched the whole process with interested eyes from their perch on the fence-rail. How beautiful it was to be sitting there in the sweet weather, working in the wholesome brown earth! Just beyond the Sweet Peas I could see my strong white Lilies springing up, a foot high already, with the splendid hardy Larkspurs behind them, promising a wealth of white and gold and azure by and by. From time to time through the calm morning, as I labored thus peacefully, I heard the loons laughing loud and clear in the stillness, and by lifting my head could see them off the end of the wharf at the landing swimming to and fro with their bright reflections, catching no end of fish and having the most delightful time, — every now and then half raising themselves from the water and flapping their wings, showing the dazzling white with which the strong pinions were lined, and laughing again and again with a wild and eerie sound. This means that a storm is coming, I know. But I love to hear them, and how devoutly thankful I am that there is not a creature with a gun on this blessed island! The loons know it well, or they never would venture in so near, while they shout to the morning their wild cries. Near me, where I had made the earth so very wet, suddenly fluttered down a ruddy-breasted barn swallow, the beauty! for on such heavenly terms are we that he did not mind me in the least as he gathered a tiny load of mud for his nest against the rafters in the barn, and flew away with it low on the wind. The barn swallows do not visit my small inclosure as often as do my nearer neighbors, the white-breasted martins. All this time the lovely day was slowly changing its early delicate colors and freshness for the whiter light of noon. By twelve o'clock the wind had "hauled" from west to south, going round through the east, and sending millions of light ripples across the glassy water, deepening its color to sparkling sapphire, and at last the sun overhead seemed to pelt quicksilver in floods upon it, and then it was dinner-time. After an hour of rest again I took up my work. All about, here and there and everywhere, I dug up the scattered Echinocystus vines and set them against the house, so that they could run up the trellises on all sides to make grateful shade by and by. A few straying Primroses waited to be moved outside the fence, — they take up so much room within, and room is so precious inside the garden. Young plants of the charming, old-fashioned Sweet Rocket had to be collected from the nooks where they had sown themselves far and near, and set in clumps in corners. Then there was a box of white Forget-me-nots some one had sent me, to be established in their places, and I finished the afternoon by planting Shirley Poppies all up and down the large bank at the southwest of the garden, outside. I am always planting Shirley Poppies somewhere One never can have enough of them, and by putting them into the ground at intervals of a week, later and later, one can secure a succession of bloom and keep them for a much longer time, — keep, indeed, their heavenly beauty to enjoy the livelong summer, — whereas, if they are all planted at once you would see them for a blissful moment, a week or ten days at most, and then they are gone. I have planted and am going to continue planting till the middle of June, in this year of grace 1893, no less than two whole ounces of Shirley Poppies in all, and when one reflects that the seeds are so small as to be hardly more than visible to the naked eye, one realizes this to be a great many.  Larkspurs and Lilies May 12th. Again a radiant day. I watched the thin white half ring of the waning moon as it stole up the east through the May haze at dawn. This kind of haze belongs especially to this month; it is such an exquisite color, like ashes of roses, till the sun suffuses it with a burning blush before he leaps alive from the ocean's rim. Again in the garden at a little after six, to find the sparrows busy tunneling up and down the bank, devouring the Poppies that I planted yesterday. How they can see the seeds at all, or why they should care to feast on anything so small, or why they do not all perish, as poor Pillicoddy proposed doing, from the effects of such doses of opium, passes my understanding. There was nothing to be done but to plant them all over and then trail through the dewy grass long boards to lay up and down, covering the bank, for protection. First, there were the small Tea Rosebushes to be set out in their sunny bed, made rich with finely sifted manure and soot and a sprinkling of wood ashes. And here let me say that all through the spring, beginning when the hardy Damask and Jacqueminots, etc., are just unfold. ing their leaf buds, it is a most excellent plan to sift wood ashes quite thickly over all the Rosebushes, either just after a shower or after you have been sprinkling them; let it remain on them for several hours, — if the sun is not shining I leave it half a day, — but then it must all be carefully washed off, every trace of it, or it will spoil the leaves. This kills or discourages all sorts of insect pests, and the effect of the ashes on the soil about their roots is most beneficial to the Roses. As I sat in measureless content by the little flower bed, carefully slipping my pretty Bon Silenes and Catherine Mermets and yellow Sunsets and the rest out of their pots, and gently firming them in the ground, with plenty of water for refreshment, a cloud of the most delicious perfume brooded about me from a bed of white violets at the left, the hardiest, faithfulest, friendliest little flowers in the world. I found two small Polyantha Roses had lived all winter in this sheltered bed; that was indeed a charming find! At the back of it grows a tall Jacqueminot, a black Tuscany Rose, and the strong white Rosa Rugosa, a Japanese variety which bears very large single flowers in the greatest profusion. This Rose is extremely valuable, easily obtained, so hardy as to be almost indestructible, and absolutely untroubled by any disease or insect plague whatever. Its foliage is always fresh and handsome, and its seed vessels are huge scarlet balls as large as an average Crab-Apple, most ornamental after the flowers are gone. But the old, old black Tuscany Rose is the most precious of all. Mine came from an ancient garden that vanished long ago, but which used to be a glory to the town in which it grew. It is a hardy Rose also, in color so darkly red as to be almost black, — a warm red, less crimson than scarlet, glowing with a kind of smouldering splendor, with only two rows of petals round a centre of richest gold. At the end of this bed is a Water Hyacinth floating in its tub, and near it, in another tub, a large pink Water Lily, kept over from last summer in a frost-proof cellar, is sending up the loveliest leaves, touched with so sweet a crimson as to be almost as delightful as the blossoms themselves. All the rest of this day was spent in transplanting Asters from boxes into the beds all over the garden, edging nearly every bed with them, so that when the fleeting glory of Poppies and other earlier annuals is gone there will still be beautiful color to gladden our eyes late in the summer, quite into the autumn days. In the afternoon I had all the many boxes of Sweet Peas brought to the piazza to be ready for transplanting, but remembering the sparrows, I covered each box carefully with mosquito netting before leaving them for the night. 14th. Sunday. A storm of wild wind and flooding rain, the storm the loons predicted At breakfast my gardening brother said, "Well, my sweet peas are all gone!" "Oh," I cried in the greatest sympathy, "what has happened to them?" for he had planted six pounds or more, and they had come up finely. "Sparrows," was his laconic reply. I flew to my boxes on the piazza: they were safe, only through a tiny crack in the net over one a bird had wriggled its little body, and pulled up and flung the plants to right and left all over the steps. But my brother's long rows, so green last night, were bare except for broken stems and withering leaves. Alas, it is so much trouble to cover such a large area with netting, he thought this time he would trust to luck, or Providence, or whatever one chooses to call it, but it is a fatal thing to do. Now he has to plant all over again, even though I shall share my boxes with him, and it will make his garden very late indeed. This time he will not fail to put nets over all! I sat on the piazza sheltered from the rain and watched the birds. Unmindful of the tempest, they skipped gayly round the garden, over and round the steps, examined all the tucked up boxes of Sweet Peas, wished they could get in, but finding it out of the question gave it up and resigned themselves to the inevitable. To and fro, here and there they went, peering into every nook and corner, behind every leaf and stick and board and stalk, busily pecking away and devour. ing something with the greatest industry. I drew nearer to discover what it could be, and to my great joy found it was the slugs which the ram had called forth from their hiding-places; the birds were working the most comprehensive slaughter among them. At that pleasing sight I forgave them on the spot all their trespasses against me. 15th. A thick fog wrapped the world in dimness early this morning; at eight o'clock it was rolling off and piling itself in glorious headlands over the coast, gleaming snow white in the sun, but here and there thin silver strips lay across distant sails and islands, lingering as if loath to leave the earth for the sky. I took the baskets of plants I had found necessary to dig up to give the rest room, and paddled across to the next island in a little lapstreaked dory, to give them to my neighbors for their flower plots. Great is the pleasure in the giving and the taking. It was such a heavenly morning, so blue and calm after the tumult of yesterday! Along the far-off coast the joyous hills seemed laughing in the sunshine, and the great sea rippled all over with smiles. From the low shores of the islands came the singing of the birds over the still water, with an indescribably quiet and peaceful effect, and as I rowed into the cove of my destination, passing the coasts of the little island called Malaga, I saw outlined against the sky the lovely grasses already blossoming among the rocks. A kingbird sat on a bowlder and meditated; there was no tree, so he was fain to be content with a rock to sit on. I passed him almost near enough to touch him with my oar, but he did not stir, not he! My errand done and the plants distributed, I hastened back to my own dear little plot again, and up and down all the paths I went, digging out every unwelcome root of grass, plantain, mallow, catnip, clover, and the rest, once more raking them clear and clean. Outside, in a bed by itself, I sunk four pots of repotted Chrysanthemums, to be ready for the windows in early winter. All along the piazza are the house plants waiting to be attended to, cut back, repotted, and the soil enriched for winter blooming. Every day I attend to them, a few at a time. I cannot spare much time from my planting, weeding, watering, transplanting, and so forth, in the garden, but soon they will be all done. Began to transplant a few of the hundreds of the main body of Sweet Pea plants into the ground, carefully covering each bed as I finished with breadths of light mosquito netting to make them sparrow-proof. As I was working busily I heard the sweet calling of curlews, and looking up saw six of them wheeling overhead. Such sociable birds! They replied to my challenge as if I had been one of themselves, and as long as their calls were answered, lingered near, but being forgotten presently drifted off on the wind, their clear whistle sounding fainter and fainter as they were lost in the distance. All the rest of this day was spent in setting out Sweet Peas, and it will take more than a whole day more to finish, for I put them all round against the fence outside, and into every space I can spare for them within. After tea I hunted slugs as usual, and scattered ashes and lime, but I really feel that my friends the toads have done me the inestimable favor of reducing their hideous numbers, for certainly there are less than last year so far. Early in April, as I was vigorously hoeing in a corner, I unearthed a huge toad, to my perfect delight and satisfaction; he had lived all winter, he had doubtless fed on slugs all the autumn. I could have kissed him on the spot! Very carefully I placed him in the middle of a large green clump of tender Columbine. He really wasn't more than half awake, after his long winter nap, but he was alive and well, and when later I went to look after him, lo! he had crept off, perhaps to snuggle into the earth once more for another nap, till the sun should have a little more power. To our great joy the frogs that we imported last year are also alive. We heard the soft rippling of their voices with the utmost pleasure; it is a lovely liquid-sweet sound. They have not lived over a winter here before. We feared that the vicinity of so much salt water might be injurious to them, but this year they have survived, and perhaps they may be established for good. May 20th. All the past days have been filled with transplanting and the most vigorous weeding. In these five days the Sweet Peas have grown so tall I was obliged to go after sticks for them to-day, wheeling my light wheelbarrow up over the hill and across the island toward the south, where among the old ruined walls of cellars and houses, and little, almost erased garden plots, the thick growth of Bayberry and Elder offered me all the sticks I needed. Such a charming business was this! So beautiful the narrow road all the way, bordered by the lovely Shad-bush in bridal white, the delicate red Cherry with flowers so like Hawthorn as to be frequently mistaken for it, the pink Chokecherry, the common Wild Cherry (which seems to attract to itself most of the caterpillars in the land), all blossoming for dear life, and among thickets of Blackberry, Raspberry, Gooseberry, Wild Currant, Winterberry, Spirea, and I know not what, such crowds of flowers! The last of the gay golden Erythroniums, the Dogtooth Violets, dancing in the breeze; the large, softly colored Anemones, now nearing their end; the banks of pearly Eyebrights; the white Violets, lowly and fragrant; the straw-colored Uvularia; the ivory spikes of Solomon's Seal, just breaking into bloom, with its companion, the starry Trientalis; the tufts of Fern in cool clefts of rocks, — of these I gathered several clumps for my fernery in the shade of the piazza. It would take too long to tell of all the flowers I saw, but one more I must mention. At the upper edge of a little cove at the southwest, where the old settlement of more than a hundred years ago was thickest, the earth was blue with the pretty Gill-go-over-the-ground, its charming blossoms covering the green turf and cropping out among the loose stones, — a dear, quaint little flower in two shades of blue marked with rich red-purple. It was too early for the Pimpernel to be in bloom, but the pink Herb Robert was out, the smallest of all the Geranium family, and I saw ranks of Goldenrod more than a foot high getting ready for autumn. To tell all I saw and all I loved and rejoiced in would take a whole day. Oh, the green and brown and golden mosses, the lovely, lowly growths along the way, and oh, the birds that sang and the waves that leaped and murmured along the shore The sweet sky and the soft clouds, the far sails, the full joy of the summer morning, who shall tell it? I was so happy trundling home my barrow load of sticks piled to toppling, and finally tipping it up at the garden gate! It took the whole afternoon to stick the Peas, and I enjoyed every moment of it. Before putting the dry brittle branches in the ground, with a small, light hoe I went all over and through the earth about the Sweet Peas, uprooting chickweed and clover, pig-weed and dog-fennel, till there was not a weed to be seen near them. When night fell I had only just finished this pleasant work. 21st. Weeding all day in the hot sun; hard work, but pleasant. I find it the best way to lay two boards down near the plot I have to weed, and on them spread a waterproof, or piece of carpet, and kneeling or half reclining on this, get my face as close to my work as possible. Sitting flat on these boards, I weed all within my reach, then roll up a bit of carpet not bigger than a flat-iron holder, put it at the edge of the space I have cleared, and lean my elbow on it; that gives me another arm's-length that I can reach over, and so I go on till all is done. I move the rest for my elbow here and there as needed among the flowers. It takes me longer to weed than most people, because I will do it so thoroughly. It is such a pleasure and satisfaction to clear the beautiful brown earth, smooth and soft, from these rough growths, leaving the beautiful green Poppies and Larkspurs and Pinks and Asters, and the rest, in undisturbed possession! Now come the potent heats that preface summer, and every- thing grows and expands so fast, the process of thinning the crowded plants must begin forthwith. Oh, for days twice as long! Yet these approach the longest days of the year. 22d. Another glorious day of heat; the sun fairly drove me into the shade to work among the house plants on the piazza. Hot, hot, and bright, and outside the garden growing things begin to pine for showers. When the sun declined toward the west in the afternoon, I sat in the shade and from the veranda turned the hose with its fine sprinkler all over the garden. Oh, the joy of it! The delicious scents from earth and leaves, the glitter of drops on the young green, the gratitude of all the plants at the refreshing bath and draught of water! The rich red Wallflowers sent up fresh clouds of incense, the brilliant and delicate Iceland Poppies bowed their lovely heads and swayed with pleasure at the bright shower. But rain is greatly needed, searching rain which shall drench the ground and reach the roots, and give new life to everything. 23d. Again hot, still, and splendid. Spent all the morning hammering stakes down into the beds near Hollyhocks, Sunflowers, Larkspurs, Lilies, Roses, single Dahlias, and all the tall growing things. Many were tall enough to fasten to the stakes, — all will be, presently. One enormous red Hollyhock grew thirteen feet high by actual measurement before it stopped last year, in a corner near the piazza. Oh, but he was superb! At night the lights from one window streamed through a leafy arch of clambering vine, and illumined him as he swayed to and fro in the wind, a stately column of beauty and grace. A black-red comrade leaned against him and mingled its rich blossoms with his brighter color, and near him were rose, pink, and cherry, and white spikes of bloom, lovely to behold. All the afternoon weeding and thinning out the plants. The large bank sloping to the southwest outside the garden is a perfect mass of flowers to be, — no weeds, for I have conquered them; but it is next to impossible to pull up plants enough to give all room. Again and again I have thinned them; now I think I must leave them to their fate and let it be a case of survival of the fittest.  Hollyhock in Late Summer 24th. Last night, after having given myself the pleasure of watering the garden, I could not sleep for anxiety about the slugs. I seldom water the flowers at night because the moisture calls them out, and they have an orgy feasting on my most precious children all night long. Before going to bed I went all over the inclosure and, alas, I found them swarming on the Sweet Peas; baby slugs, tiny creatures covering the tender leaves and the dry pea-sticks even, thick as grains of sand. I was in despair, and though I knew they did not mind ashes, I took the fine sifter and covered Peas, sticks, slugs, and all with a thick, smothering cloud of wood ashes. Then I left them with many misgivings and went to bed, but not to sleep, for thinking of them. At twelve o'clock I said to myself, You know the slugs don't care a rap for all the ashes in the world, but the friendly toads may be kept away by them, and who knows if such a smother of them may not kill the precious Peas themselves? I could not bear it any longer, rose up and donned my dress. ing gown, and out into the dark and dew I bore the hose, over my shoulders coiled, to the very farthest corners of the garden, and washed off every atom of ashes in the black midnight, and came back and slept in peace. These are most anxious times on account of the slugs. Now, every morning when I rise I go at once into the garden at four o'clock and make a business of slaughtering them till half past five, when I stop for breakfast. If the day is pleasant they are all hidden by that time, for they dread so the touch of the sun. But in the hoary morning dew they delight. This is the hardest part of my gardening, and I rejoice that not one person in a thousand has this plague of slugs to fight. It is so difficult to destroy them; to see their countless legions and feel so helpless before their numbers, to find one's most precious favorites nibbled and ragged, and everything threatened with destruction is a trial indeed. I carry a large pepper-box filled with air-slaked lime and shake it over them everywhere. They are so small this year that it destroys them; they turn milky and miserably perish, but the next morning there are just as many more to take their places. Still I patiently persevere, carefully washing off the lime, so anxious lest it should harm the plants, and killing by hand all the larger monsters. In that most charming old book, Gilbert White's "Natural History of Selborne," I find he speaks of these arch enemies of mine as "noticed myriads of small shell-less snails called slugs, which silently and imperceptibly make amazing havoc in field and garden;" adding in a note, "Farmer Young of Norton Farm says that this spring (1777) about four acres of his wheat in one field were entirely destroyed by the slugs, which swarmed on the blades of corn and devoured it as fast as it sprung." Poor Farmer Young! I deeply sympathize with him and his long buried trouble! Again White says: " The shell-less snails called slugs are in motion all winter in mild weather and commit great depredations on garden plants, and much injure the green wheat." There was a happy time when such a thing as a slug was unknown on my island, and I well remember the first that were brought here among some Moonflowers that were imported from a distant green-house. I saw them adhering to the outside of the flower-pots and did not kill them, never dreaming what powers of evil they would become! 25th. Every day the garden grows more interesting, more fascinating. Buds full of promise show themselves on the single Dahlias whose seeds were only planted in February; on the Rose Campions, the perennial kind, on the tall white Lilies. The Hollyhocks are thick with buds, and rich spikes head all the boughs of the Larkspurs, and as for the Roses, they are simply wonderful. The Tea Roses are loaded with buds; on one of the Polyanthas that lived all winter in the ground I counted fifty-two, and it is a tiny bush not more than a foot high. The dear old Sweet Rocket is blossoming in every corner, sending up its grateful perfume. Now come days of great anxiety about the Margaret Carnations that I have so loved and watched and tended since the first of March. They were splendid plants, full of health and strength and all ready to bloom. Alas, I saw, a day or two ago, the leaves turning yellow. I knew too well what that meant. There was but one thing to do. Down on my knees I went this morning, and bringing my face close to the ground, began pulling apart the central shoot in each plant, where the sickly color hung its flag of distress for a signal. Down, down a cruel length, into the very heart and core of each precious stem I tore my reluctant way to find that abomination of which I was in search, namely, a short fat lively white worm; for him I probed and brought him up on the point of a pin, and having a small quantity of alcohol at hand for the purpose, dropped him into it forthwith, for instant and complete destruction. Over forty of these beasts did I destroy, and left the tattered Pinks to rest and recover, if they could, poor things, after such a terrible experience! These worms seem made for all fragrant Pinks; as far as my experience goes they never attack anything else. How in the world, I wonder, do they know where the Carnations are planted and when to come for them? Such a scene of devastation as is my pretty bed of Pinks of which I was so proud, dwarfed and yellow, with their gnawed-off leaves strewn about all over the ground! But they will put out side shoots and patiently strive to fulfill heaven's intent for them, of which they are conscious from the least root-tip to the end of every battered leaf. There is something pathetic as well as wonderful in the way in which these growing things of almost all kinds meet disaster and discouragement. Should they suffer misfortune like this, — the lopping of a limb, or the losing of buds, or any sapping of their vitality, — if the cause is removed, they will try so hard to repair damages, send out new shoots, make strenuous efforts to recover the lost ground, and still perfect blossom and fruit as nature meant they should. There is a lesson to be learned of them on which I have often pondered. June 3d. This has been an exciting day, for the Water Lilies I sent for a week ago came in a mysterious damp box across the ocean foam! I had made their tubs all ready for them, putting in the bottom of each the "well-rotted manure," and over this rich earth and sand mixed in proper proportions. These tubs, or rather large, tall butter firkins, stood ready in their places along the sunniest and most sheltered bed in the garden. Oh, the pleasure of opening that box and finding each unfamiliar treasure packed so carefully in wet moss, each folded in oiled paper to keep it moist, and each labeled with its fascinating name! The great pink Lotus of Egypt, the purple Lily of Zanzibar, and the red one of the same sort, the golden Chromatella, the pure white African variety and the smaller native white one, the yellow Water Poppy and the little exquisite plant called Parrot's Feather, that creeps all about over the water and has the wonderful living, metallic green of the plumage of the handsome green parrots. These, with the flourishing Water Hyacinth I already had growing in its tub on the steps, and the bright pink Cape Cod Lily, make ten tubs of water plants, — a most breathlessly interesting family And I must not forget another tub of seedling Water-Lilies that I am watching with the most intense interest also. It took most of the long, happy day to plant all these in the rich wet mud and settle them in their comfortable quarters. I laid some horseshoes I had picked up at different times, and saved, round the roots to hold them down temporarily, while I gently flooded the tubs with water and rejoiced to see the lovely leaves float out on the surface fresh as if they were at home. Then I sifted clean beach sand over the earth about them, to the depth of an inch or more, to hold the soil down and keep the water clear, and all was done. What delight to look forward to the watching and tending of these new friends! I find myself wondering what enemy will attack these, for surely something has been made for their destruction, which I must fight! There is not a growing thing in the garden that has not its enemies and destroyers, fortunate if it has only one. Just at this time there is a rampant little snuff-colored spider which comes in from the grass and fastens upon tender growths in the borders about the house, covering the succulent leaves and stems of Wild Cucumbers and Morning-glories, and even Nasturtiums and Cornflowers, so thickly that the plant is not to be seen at all for them; they are like a brown glove over every leaf, and they suck every drop of sap out of the plant, leaving it perfectly white. They are fatal on the Sweet Peas, of which they are especially fond. No poison known to me has the slightest effect on them; nothing but water turned on with the hose in floods disturbs them. This washes them away for the time being. It has to be repeated, however, many times a day, for they recover from their drenching and return to their work of devastation with renewed vigor. Fortunately these do not, like the slugs, last forever; they are gone in less than six weeks; but they keep me busy indeed while they stay. I am obliged to spend a good deal of time just now hunting and destroying different bugs and worms and so forth. The blue-green aphis appears on certain precious Honeysuckle buds, and must be vigorously syringed with fir-tree oil before he gets a foothold and spreads his hideous legions everywhere. Also the lively worm that ties the Rose leaves together and gobbles them up and hides in a web within them, that I may find and crush him; and the white thrip which calls for hellebore, on the under side of them, and many more, must be attended to before they wax strong and bold in their villainy and defy me. A curious plague, if I may call it so, has come upon the little garden, in the shape of the delicious edible mushrooms, Coprinus Comatus, which come up all over the place and with slow strength heave the ground and my flowers into heaps, thrusting handsome long ivory-white, umbrella-shaped heads on stems a foot long, up high above and over most things in the beds. But these are eaten as soon as they appear, and are not such a very great trial, though I would rather they left my dear flowers undisturbed. |