| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2012 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

XII

GRAND RAPIDS OR CHIPPENDALE WHICH? YOU can't get very far in discussing an early American house without also considering its furniture. The obvious furniture pieces to use in such a house are antiques or reproductions. But let's get some things straight. There isn't a great deal to know about American antique furniture. It covers a period of only about 150 years 1650-1800. During this time the Colonies were so busy fighting wars, taming Indians and building an Empire that creative art was naturally neglected. Most American pieces are copies. It's far different in Europe whose furniture history goes back a thousand years with artists and artisans of every civilized race creating new forms. Authentic examples of the very earliest homemade Colonial furniture are almost unknown. For example, there are no early beds and but a few home-made chairs in existence. Early furniture was probably so crude that when something better came along, what they had first landed in the woodpile. We can only guess how early houses were furnished from inventories. These inventories mention chests, cupboards, benches, tables and chairs. Probably every passenger on the Mayflower had a chest a crude sort of box for personal belongings. Later, drawers were added to chests. There are good examples of the so-called Hadley and Connecticut Chest dated about 1675, but at that time drawers had been added as well as crude carvings and initials of the owner. Chests have since grown legs and graduated into highboys and lowboys. The inventory of the household effects of Thomas Gregson of New Haven (drowned with the "great ship" in 1645) mentions that his parlor contained, in addition to other things, two tables, one cupboard and cloth, one carpet for table, eight chairs, thirteen stools, four window cushions and ten curtains. When we consider the massive character of early furniture as well as the small size of rooms, there must have been but little room left for the Gregsons when the furniture was in place. This still happens in houses even to-day. Almost every American likes antique furniture. It isn't conceivable that the present craze for antiques is a passing fancy or a desire to appear ''smart.' Old furniture, after the first Jacobean furniture was replaced by lighter pieces, embodies three essential qualities beauty, utility and simplicity. While most of us take satisfaction in these reminders of early days, you occasionally meet with a scoffer who claims to see nothing beautiful in antiques. When such critics finally see the light, they fall harder than the man or woman who has always subconsciously accepted antiques as one of the beautiful and enduring experiences of life. One thing is certain, there are more antique authorities to-day than there are antiques. You can be a sort of authority over night. But it takes time to be an antique. Just learn a few stock expressions like ladder or fiddle back, Boston Rocker, highboy, or Stiegel and Sandwich glass and there you are. Most people can't dispute what you say. But whether Americans know much about antiques or not, they are proud of their history. Antiques around the house are a sort of mute evidence that even if only one person in every seven in New York to-day had a grandfather born in America, your grandfather was born here a direct descendant, perhaps, of those mythical "three brothers" who drove a yoke of oxen to Maine or New York state or Kalamazoo and settled there. How many family trees are rooted in the ''three brother" legend? I wish mine was. The first authentic Miller, I can find record of, evidently did not care for oxen. He was said to have been hung in Rhode Island for stealing a horse. Even if he spelled "God" in his will with a small "g" and two capital "Ds", he lived in a house with a big, fat chimney. I'm sure of that. People who claim to know a lot about antiques sometimes take a supercilious attitude toward those to whom they are a Chinese puzzle. Anyone can master the rudiments with but little study. Then they can go as far as they like. I am only talking about furniture now. If we include china, glass, tapestries, household appliances and architecture, the subject is endless. Some old pieces of furniture are said to have come over on the Mayflower, Probably twenty Mayflowers wouldn't hold them all. The Mayflower was a tiny ship of eighteen tons crowded with 102 souls. When she took on the passengers of the Speedwell, which leaked too badly to go on, in addition to her own passengers, she couldn't have had much room for furniture. Furthermore around 1620, beds and chairs and tables were so bulky that a single piece would take up as much room as a Myles Standish or a couple of Priscillas. Authorities believe that the Governor Carver chair is a true Mayflower piece. It has such generous arms and legs that in its sternness it looks almost like some of the Pilgrim Fathers themselves. Beds were really small rooms, so large that a whole family slept in one bed. Among the yeomanry, chairs were so unusual that some houses had but one. The rest of the family sat on benches or on the floor. Benches and trestle tables were among the first types used. Trestle tables were long narrow affairs pegged together and resting on "x" shaped trestles like a saw buck, or on an inverted "T". If you can find an original table of this type in some barn or woodshed it will be worth a pile of money. About this time appeared two other types of tables butterfly tables and gateleg tables and shortly after tip tables. The big idea of these tables was the same to fold up against the wall when not in use. About 1675 through contact with Europe, early furniture designs of the Pilgrims practically disappeared. It was too clumsy to last. Everything became lighter and daintier. Why the colonists, once emancipated from the furniture of the 1600's, should ever have gone back to it in 1800, will remain as great a mystery as bustles and hoop skirts. After modern furniture forms were perfected by Chippendale, Sheraton, Heppelwhite and Adam at the close of 1700, there have been but few permanent changes. If we took all of the Sheraton and Heppelwhite chairs out of the world to-day, there wouldn't be many chairs left. These names are sometimes called the "big four" of furniture; they were famous even when they lived. Robert Adam, one of six brothers, was a Royal Architect. He never made any furniture, but he designed it. English furniture makers set the world's standards for good taste. Chippendale applied the so-called Cabriole or Dutch Bandy legs of Queen Anne furniture to about everything. Maybe he was bow-legged himself. Feet were made in a dozen styles snakes, ball and claw, Spanish, spade and fluted. American furniture makers created but little new. They simply copied the English. Workmen frequently had learned their trade in England. Each of the ''big four" copied the best creations of the others. Yet each had certain distinctive styles of his own. Sheraton and Heppelwhite went in for straight tapered legs. Chippendale copied certain Chinese designs. Sheraton and Chippendale published books of furniture designs to help make their designs standard. There are no early chairs to be found any better than the slat-back chairs, sometimes called John Alden chairs, that became popular about 1700. These and Windsor chairs were made in great quantities in America. It is possible to find real antiques in both designs. Any furniture store has perfect reproductions. About 1750 Benjamin Franklin put rockers on a slat-back chair. That was when the rocking chair was born. Probably the most comfortable of all chairs is the so-called Boston or Salem Rocker, painted black with gold designs. Nearly every old New England farm house has one. They are not especially valuable as antiques because even the oldest are not more than 100 years old. Genuine American Windsor chairs simply means chairs similar to the English Windsor made in America. American workmen greatly improved them, and even to-day no one has succeeded in designing a better all-around chair than a Windsor. This includes old John W. Mission and Bill Morris who invented the Morris chair. George Washington had fourteen Windsors on his porch at Mount Vernon. In America there was one outstanding furniture designer Duncan Phyfe, a Scotchman. While like all the rest, he freely copied the work of his contemporaries, he also made such exquisite furniture from his own designs that his name stands alone. In this country there are no lovelier dining-room tables in the world than Phyfe tables with their central pedestals carved with leaves and their graceful curving bases ending with brass feet. Practically every fine American home that could afford it had a Phyfe table. Phyfe also made chairs, tall clock cases, and beds, but his fame is secure for all time through his tables. Phyfe was at work when Napoleon decided that he wasn't satisfied with the graceful creations of the master furniture designers who preceded him. He wanted something that would reflect his own dominant personality. Then the blight of the Empire Period struck the land with huge ponderous dressers and tables, ugly animal feet, everything big and clumsy, using enough wood for one piece to make two or three of Sheraton's. To fit such furniture people built houses equally ponderous and gross. Duncan Phyfe found, before he died, that he too would have to make Empire furniture to keep in business. Remember he was a Scotchman. But he publicly called it "butcher" furniture and in the privacy of his own home he doubtless added a few adjectives. Mahogany wasn't known until 1720, an even hundred years after Plymouth Rock. Even then mahogany was a great rarity until Chippendale made it the world's most popular wood for furniture. So watch your step when you claim that your mahogany tip table is more than 200 years old. Just a word about the antique authority in your town. There is always at least one. This is the lady or gentleman who sees an old piece and with arching eyebrows says, ''Chippendale, I see," or ''a splendid Sheraton piece." There are practically no genuine pieces outside of museums made by the "big four." These English furniture makers couldn't have been able to make even a small part of the furniture required at home, to say nothing of the colonies. Experts find the greatest difficulty in deciding whether an English piece even is genuine or a copy. Practically all the furniture found in old American houses is of American manufacture. Long before the Revolutionary War, there was a decided movement here, a sort of boycott against buying English made goods. For example, in 1765 Samuel Powel was traveling in England. He wrote his uncle, Samuel Morris, about the advisability of bringing back some English made furniture for his magnificent Philadelphia home. Uncle Samuel replied: "In the humour, people are in here, a man is in danger of becoming invidiously distinguished who buys anything in England which our tradesmen can furnish."

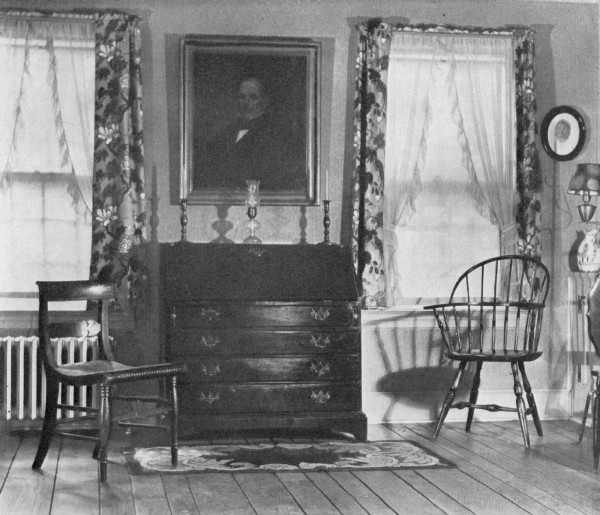

The Reproduction of a Duncan Phyfe Dining Table and Chairs. The Originals are Museum Pieces and almost priceless. Tables with Central Pedestals are the most notable feature of Phyfe's work. The early Empire Sideboard was purchased for $5.00 and restored at a cost of less than $1.00.  Our old Slant-top Desk is Cherry. The Portrait is that of my Grandfather. It is easily 200 years old. Note the Random Width Oak Plank Flooring.

This did not apply to textiles, however. Colonists weren't so fussy about silks, brocades, velvets, linens and tapestries. The valuable cargoes captured by Colonial privateers sometimes contained the choicest fruits of foreign looms. When the good ship, Hannah Bradford, or Crest of the Wave, came home from a successful cruise laden with textiles, naturally these goods had to be sold. No one had any compunction that they were really stolen goods obtained under legalized piracy. It probably would have been as unusual for a thrifty Puritan Yankee to buy foreign furniture then as it would be to-day. Who do you know that would to-day send to Calcutta for a table, when mail order catalogs and Grand Rapids are so much handier? One hundred and fifty years ago newspapers were carrying advertising of local cabinet makers and chair makers everywhere. John Brinner advertised in 1762 that he and the six "artificers" he brought with him from London were prepared to supply "Desks and Book-Cases, Writing and Reading Tables, China Shelves and Cases, Commodes and plain Chests of Drawers, Gothic and Chinese Chairs, Sofa Beds, Settees, Couches, Easy Chairs, etc. etc." Every town large and small had its local cabinet maker. Furniture was made in the shop where it was sold. When we consider that by 1675 there were 70,000 people living on the Atlantic seaboard using chairs, tables and beds, and that there were 700 ships owned by Americans and trading with the world, it becomes increasingly difficult to trace the origin of any old piece of furniture. There are a few men and women who know antiques as well as we know the back of our hand. They seem to be gifted with a sense by which they can tell the difference between an antique and a fake. When they say "Heppelwhite," they mean it. That is why, in any of our museums devoted to early Colonial art, a majority of the labels read ''Sheraton influence" ''Chippendale inspiration" and almost never "Genuine." It is almost out of the question to furnish any home with antiques throughout, unless you are prepared to pay as much for the antiques as you do for the house. Our dining room has an authentic reproduction of a San Domingo mahogany Duncan Phyfe table and six chairs copies of museum pieces that would cost ten thousand dollars to-day if actually made by Phyfe. A reproduction is frankly what it claims to be. A so-called antique sometimes is the rawest kind of a fake. Thousands of so-called antique twin beds have been sold in America. There are no genuine twin beds. Beds that held five or six were not uncommon. Beds that held but one were unknown. Genuine pieces in good condition are often too valuable for general use, especially chairs of the early days. If you want to see a perfect example of "when a feller needs a friend," let a fat man sit in an old rush-seat ladder-back 200 years old, and watch the expression on the owner's face. Most families have some antiques. Usually they are their choicest possessions. A slant-top, or so-called Governor Winthrop desk we have was made by my grandfather's grandfather who was a cabinet maker. It dates back to 1700 and looks like cherry, but it is still in use. If we had an authentic chair of that period, we should put it in a glass case. Even the most casual inspection of a first class furniture store reveals the fact that there are only two dominant styles of furniture, antique reproductions and modernistic furniture. Far be it from me to pass judgment on the latter the so-called "gaga" art of the intelligentsia, squares and cubes and dynamic splashes. Perhaps the judgment of Greenwich Village will be justified by posterity. We may be in the birth of another renaissance and don't know it. Your guess is as good as mine. But before we turn to the wall the pictures of Adam and Chippendale and Phyfe, and put in their places men who wear their hair long and women who wear it short let's wait a bit. Anyone who contemplates the purchase of furniture should consider the modernistic trend seriously. We don't change our dressers and beds with every change of seasons. What we select now may be with us many years. A tour of the stores will reveal the apotheosis of the humble ''T" square applied to furniture. You will see colors as vivid as a Ziegfeld chorus, trick angles and amazing lines that will mean little to us at first and even less than that when some devotee of ''gaga" works himself up into a fever heat explaining them. He will tell us how we must feel new art before we can see it whatever that means. After you have soaked in "gaga" to your heart's content, ask for the antique reproduction department. The elevator man will tell you even if he disapproves. Take a good look at the reproductions of Windsor chairs, Virginia sofas, maple beds, ladder-back chairs, hook rugs, and dainty tables, some of them made with tops to look like an apple pie, chests of drawers with a looking glass hanging over them. Which do you vote for? Well, all I have to say is that if you intend to build a period house, for goodness sake don't furnish it in modernistic furniture! It would be as appropriate as Frank Stockton's raw oyster in a cup of tea. Don't disregard this solemn warning unless you are prepared for a great surprise. Some night in the dark of the moon, with a hoot owl in a nearby tree and the wind moaning through the hemlocks, you will wake up to find your ''gaga" bedroom filled with strange, wraith-like creatures. Look them over carefully. Their funny clothes and serious sad eyes may give you a big laugh. There will be old Simon Willard of Boston whose banjo clocks are the most beautiful clocks the world has ever known. Then perhaps will also appear Robert Adam, most famous of the six Adam brothers, who was the most powerful influence in the creations of Sheraton, Chippendale and Heppelwhite. Baron Stiegel will try to get there and tell you how he used to have cannons mounted on his house to be fired when he drove through the gates. But in spite of his eccentricities his glassware has never been duplicated anywhere in the world. Maybe the old codger of Windsor, England, may drop in, who, when he designed the Windsor chair, said, ''Beat that one if you can." He will probably be chuckling in ghoulish glee because no one ever has. These will be uninvited guests in your early American house. They just dropped in hoping they would see some old friends. In such a setting this ''T" square furniture is something new to them. That is why they will point long bony fingers at you as they advance toward your bed. No one will say a word but their eyes will be inexpressively sad. ''Quick!" they are getting closer. "Snap" on goes the light. Ah, they are gone. You are left alone with your "gagas." Now let's get down to brass tacks. If you attempt to furnish your house throughout with antiques it is no longer a home. It is a museum. You should charge your guests admission. Furthermore they will feel thoroughly uncomfortable in a setting of such treasures. You are certain to get various pieces not at all adapted to your needs. You are making a great sacrifice for an ideal. It isn't because antiques are antique that makes so many people like them. Their charm comes from the fact that they are graceful, pleasing to the eye. Some antiques are ugly, Jacobean Wainscot chairs, for example. Don't think of a so-called Virginia sofa with its eagles and swans and lyre ends, its graceful curves, as good in design merely because it is relatively old. If you happen to possess such a sofa either an original or a faithful reproduction just pick it up (metaphorically, of course) and hurl it in the general direction of the Davenport maker of Davenport, Iowa. Say, "Here you, beat that one if you can!" Let your attitude be like that of the designers of the Parthenon and dare the countless generations that followed to equal what they built in Athens, B.C. If you don't like a thing, don't have it around just because it's old. And don't be too fussy about a few dates. Some antique fans are singularly gifted liars anyway. In our daily life we are surrounded with antique reproductions right now and never give them a thought. Curtains, rugs, picture frames, dishes, silver, lamps, china you can't possibly escape Colonial influence. And yet as a setting for things of this kind why is it that we so rarely see some little gem of a house with its green blinds, its hollyhocks peeping over a picket fence, its old-fashioned garden of crocuses, foxglove, larkspur, Canterbury bells? Why should such houses be so scarce? They are the easiest kind of houses to build, really nothing but a box. Every mill that makes sash, doors, trim and blinds has in stock practically everything that goes to make up such a house. In the cities we are now in the midst of a modernistic movement. Huge office buildings and hotels show lines and effects that are distinctly different. Perhaps new lines are necessary for fifty-story buildings. After the thirty-ninth story the low squatty effect would be lost anyway and I don't believe a central chimney would help much if it were 400 feet in the air. But small houses, the kind that millions of people live in, haven't varied much in size in two centuries. They have merely become increasingly ugly. When you replace the furniture you now have with antiques or reproductions, a piece at a time, you get more real pleasure than those who can afford a complete job of refurnishing all at once. There are many excellent sources for reproductions to-day. Authentic copies frequently are made exactly like originals. When purchasing you should get information as to the exact source of the reproduction. This would give your furniture an added value. Some day antique reproductions will not only be accompanied by data relating to the source and approximate date of the original, but if possible will be accompanied by a photograph of the original piece and any other data relating to it that might be interesting. Such information would be exceedingly easy to get. It would add immeasurably to the interest and value of the piece. It would almost be like making a pilgrimage to the shrine of Thomas-a-Becket, to visit the house or museum where the original of your reproduction was shown. The average furniture store clerk will not be able to give you much information. In fact, their fund of misinformation is frequently amazing. One recently told me that Duncan Phyfe never made any chairs and that the only chairs appropriate for a Phyfe table were Chinese Chippendale. The store where this clerk works is less than twenty minutes' ride from the American wing of the Metropolitan Museum. A single afternoon there would give him a fund of information which would be of the utmost value in his business. Don't depend too much on clerks. And don't buy anything you don't want, merely because it is old. The subject of antiques is endless. Frankly I know but little about it. But I do know that a house of the type of ours requires antique furniture throughout and some day we hope to have it. If you really like antiques, and have sufficient money and time, a quest for antiques purchased at their original sources farm-houses and attics is a fascinating adventure. One man I know has made this his hobby. While he could easily afford a Rolls Royce, when on such a quest he drives around the country in an old "Model T" Ford. He stops at a farm-house ostensibly to solicit subscriptions to a farm magazine. Then he uses his eyes and ears. Before he leaves he asks the owner if he has any antiques for sale. He has picked up hundreds of pieces this way, Currier and Ives prints. Sandwich glass, Windsor chairs, old flintlocks, bottles, tall clocks, mantel clocks, books, in fact everything that possesses a value. He has occasionally run into pieces actually planted in a farm-house, being the rawest kind of fakes. But such cases are rare. The chief trouble a collector has to-day is to get pieces at a fair price. In spite of a popular impression, antiques except in rare instances are not worth fabulous prices. An ordinary chair or table shouldn't bring more than a few dollars unless it is in exceptional condition and of a type that is hard to find. An old farmer I know has a tall pine clock plainly dated 1820. The works are gone and the case is practically falling apart. I offered him five dollars for it. He asked three hundred. One of the best protections of the amateur against fakes is the price at which they are offered. I almost bought a slant-top desk once for thirty dollars at a county fair. It had secret drawers, curved mahogany drawer fronts and hardware of solid hand-made brass. Even a fake would have cost more than this to make. Antiques are still obtainable. Within the past year I have secured two pieces that are invaluable to us. One was bought in an auction room and the other from a storage warehouse. I am restoring them both. Speaking of restoring, some people look upon restoring furniture as one of the mysterious arts that only an expert can attempt. The work of restoring an old piece of furniture, more or less intact, is a simple job that almost anyone can do. It merely consists in thoroughly cleaning the piece by removing all the paint or varnish with paint remover (which is sold in every paint store) then scraping or sandpapering, and giving it a new finish. You will find in replacing missing hardware that you can obtain exact duplicates of drawer pulls, hinges and locks at any large hardware store. One of life's great moments is to remove the paint from an old piece of doubtful wood and find underneath mahogany or maple or possibly apple or cherry. We had an old sideboard that for years never seemed to find its place, so it remained in the cellar. It was painted a dirty brown. One day, when I was working on another piece, I tentatively applied a little varnish remover to one of the drawers of the sideboard. When the varnish remover began to penetrate I wiped off the spot, and to my utter amazement found that this old sideboard was gorgeous crotched mahogany. If I had seen it restored in an antique shop, I should almost have hesitated to ask the price. I completely refinished the piece at a cost of less than one dollar. It is now one of our most cherished possessions although it is early Empire and holds the honored place in our dining room. Don't be afraid to try your hand at restoring old pieces. You can't do them much harm even if you get tired of the job. Try your hand at one old piece at least, say a picture frame or chair. The only skill you need is the ability to apply varnish remover without getting it in your eye. When you get to the original wood, you can either revarnish it with white shellac and then wax it, or, if the color isn't just what you want, you can first apply a mahogany or maple stain. The true early finish is hot boiled linseed oil and beeswax. Real antique authorities scream with horror at the sight of varnish on an old piece. But most people are not so particular. Don't use a combined varnish stain. Cabinet makers never use that. They stain the wood first to the desired shade and then wipe off the surplus while it is still wet. When it dries they apply the varnish or wax. If you are in doubt about the finish, you should experiment on some obscure spot and see whether you get what you are after. If not, the same varnish remover that removed a surface two hundred years old will remove yours as well and you can start all over. We restored the Governor Winthrop drop-front desk shown in one of the pictures. It was exceedingly simple. To begin with, the desk originally had eight small drawers. There were but three left. I made the other five out of pine for the sides and bottom, and light mahogany for the front. The base was gone, so I replaced that also with one of mahogany. The mahogany came from an extra dining-room table-leaf that we never used. When the cabinet work was finished, I scraped and sandpapered it all down to the original wood, supplied the missing hardware, stained and shellacked and waxed it, and it looked like new. There is nothing to the work which any boy in a manual training class should not be able to do. When it comes to applying missing veneer or attempting any carving or delicate moulding work, that is another story. But there is no reason why some rare old pieces you have should be pining away in the attic because you can't afford a real job of restoring. Try your hand at it. You will be amazed to see how simple it is. And your friends who haven't tried it (except the experts) will come to admire and say, "How smart Fred is," when Fred knows that it really would have been more work to wash the car or mow the lawn. To be a real student of early furniture involves knowing a lot of things besides furniture. We must study the racial characteristics of the people whose furniture we are studying. We would find that the Dutch, for example, in America had furniture that was different from the English, and that the French had still a third kind. Someone calls a piece ''Jacobean," because when our forefathers were Puritans that was the kind they used in England. But which Jacobean? There was early Jacobean. Then when Cromwell was riding high, they simplified it and called it Cromwellian. Then when Cromwell lost his power they went back to the early Jacobean again, and called it Restoration. And then William and Mary came in, and Dutch furniture was popular for a time. Meanwhile, without reference to England or even Europe, pieces were brought to America from other countries. I recently saw a high chest of drawers that defied the analysis of the antique sharp who had it. It wasn't like anything he ever saw. The answer was that it was purchased in Korea. Not one person in a thousand knows much about the subject. Everyone knows an antique when he sees it or thinks he does, which is about the same. There are some necessary articles of furniture to-day for which there are no antique prototypes a radio cabinet for example. A radio cabinet always strikes a discordant note in a home furnished in period reproductions or antiques. Up to the present we haven't been able to find a single cabinet that seems to fit in with the furniture we hope some day to have. Radio cabinets are generally terrible. About ninety-nine per cent are walnut. It is true that there are so-called period cabinets but it is only a name. Put them in company with antiques, and they don't belong. I would like to tell about a cabinet that will harmonize. The only trouble is that it isn't made yet. It will be easy just a plain pine box with simple legs and H.L. hinges and a hand-forged catch. The whole thing should cost ten dollars. There are many old pieces that with very little change could be made to house the gadgets and dingbats of radio. Open a pair of doors and there it would be, dial, loud speaker and everything. If any of the readers of this book have secured a radio cabinet that really seems to belong with hook rugs and plank floors, they will place me in their everlasting debt by sending a photograph of it. But if it looks anything like the kind I see in radio shop windows, if it's all the same to you, I'd rather not hear anything more about it. Pianos also present a problem in striking the right note amid early surroundings. You can't expect a baby grand to look much like the spinets and harpsichords of our ancestors. But you can get pianos in maple or mahogany that seem to harmonize. If you are rich enough you can even have a special cabinet and finish for yourself. Pianos have been with us so long that they are like the groom at a wedding, they may be regarded as a necessary evil. As a matter of fact, harpsichords are quite similar in shape to baby grand pianos resembling a harp on its side, and as they were in general use even as early as 1660, we can accept pianos as modern adaptations of harpsichords. Personally I don't believe in housing an old harpsichord that doesn't work. In fact, spinning wheels that don't spin, clocks that don't run, chairs you can't sit on, belong in a museum, not a house. In saying this I am humbly conscious of the fact that there will be an audible muttering that may even swell into a roar of protest. But, this book is merely a statement of my own opinion. There are so many things both useful and beautiful in the list of antiques, andirons, rugs, desks, chairs, tables, dishes, pewter, that things just kept around because they are old is a little like the stuffed pug dog of the Victorian era. Most houses are overfurnished anyway and cluttered up with a labyrinth of furniture. Why add to it things that have no possible use? Just to have a period house it isn't easy to junk things that you have grown up with and have learned to look upon as old friends. This is particularly true of things that get out of order never to be fixed, pictures of people that you never see, old things that have been replaced by new, vases and bric-a-brac for which there never seems to be just the right place, or bound volumes of magazines of 1890. In my early days we had in our farm-house a framed picture of our house completely made of cork. Alongside of it on the top of a desk was a huge glass cage filled with stuffed song-birds, and several crayon portraits made from photographs. They were pretty terrible. But I don't want any comments. Probably you have just as terrible junk in your own house. The difference is that your what-not and tidies and Roger's groups and framed resolutions of the Grand Jury commending the meritorious service of your Uncle Podger are overlooked by you. But they would stand out like a sore thumb to your visitors, if you kept them around now. Whatever furniture you select, give a thought to the children those helpless little shavers who trust you so implicitly. Have you forgotten the time when your in-laws wished off hat-racks on you? What has become of old John W. Mission now ? Where is Fred J. Hat-rack and his sister Lazy Susan one of those 'merry-go-round" affairs designed for the centre of the table to save the waitress from unnecessary steps, especially in families who have no waitress, and where "Please pass the butter" is considered a social error. I don't seem to find Fred and John in the furniture hall of fame. Wherever they have gone is the place where Willie Gaga will go too, if you ask me. |