| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2012 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

II

AN ADVENTURE IN HOUSE PLANNING

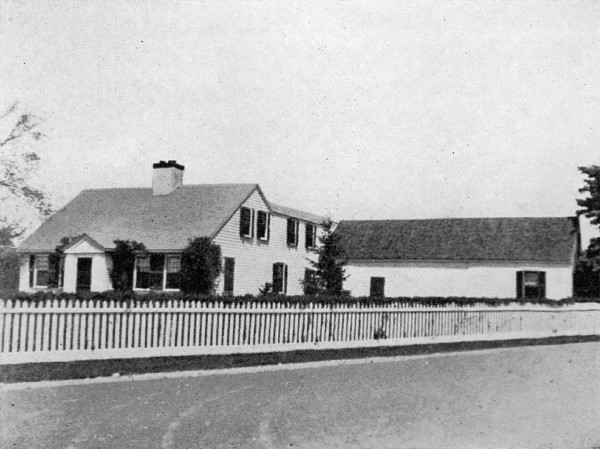

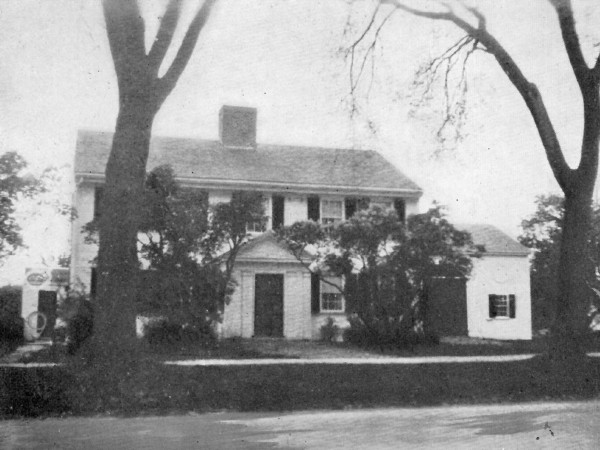

The famous Alden House at Duxbury where John and Priscilla lived and Died; 278 years old and still in good condition. This Shrine of the Mayflower Society is now a Museum.  Built in Cambridge, Mass., in 1657, almost under the shadow of Harvard University. This is a Duxbury Barn Type with a one story rear, a splendid example of the Clustered Central Chimney.  On the Road to Lexington Green and Concord. This House was the Home of one of the Minute Men summoned by Paul Revere. This was an Old House even then. (April 14th, 1775.)

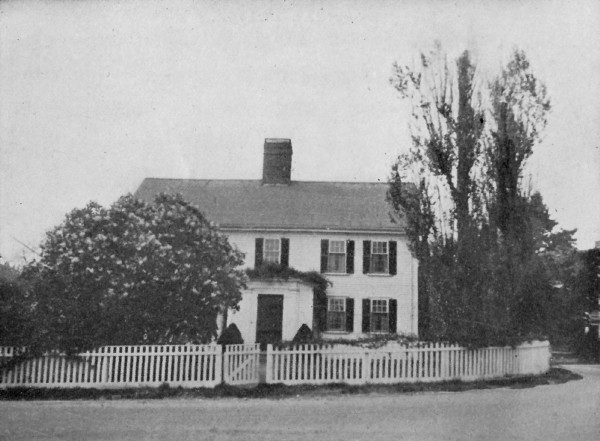

An Old Timer on the Road to Plymouth. The Picket Fence was necessary to keep Grazing Cows along the Road out of the Dooryard.

I WAS obliged to live in Boston for a year but moved back to New Jersey at the first opportunity. There are many fine sights around Boston. The train to New York is one of them. But that brief contact with New England's architecture inspired the little house with the big chimney described in this book. I have lived in all kinds of houses, brick, stucco, bungalows, brownstone fronts, even an adobe hacienda in Mexico with an inner courtyard or patio. I had always felt that was a picturesque type of architecture until a tarantula as big as a soft shell crab wandered into my room from "the inner courtyard or patio" and insisted upon sharing my bed. I sat up for the balance of the night lest some of his relatives might drop in to look him up. Toward morning I had reached the farthest south in my enthusiasm for Henri Fabre and his accounts of the fascination of making pets of spiders. If you hope that your house will give you a fresh thrill every time you look at it, don't think you are going to find it in the ready-cut boys' catalogs. It has to possess an elusive charm almost like a Florida sunset or a vagrant whiff of new-mown hay. True, it will have to have rooms and second mortgages, and a kitchen sink, but those are not the things you will learn to love. What you will love is the kind of a house that looks as though it had "Welcome" on the mat for you and your friends, a fireside so friendly that when you have arrived there, that's all there is. There isn't any more. After planning, building and living in a half dozen types of houses, I am now sure that in the entire field of architecture there is no type of small house so enduring in the continued satisfaction it will give its owner, or that will excite more real admiration from friends and neighbors, than the central chimney, white farm house with green blinds, so common in New England and almost a stranger to the rest of the United States. (Period. Deep breath.) Before we attempted to plan such a house, we became saturated with the spirit of these surviving outposts of our early history in New England. We spent a whole summer cruising around the roads radiating out of Boston. We photographed any old timer that had ''it". Some pictures were merely doorways or vistas of picket fences and gardens. We studied details of arches and windows. Soon we had about one hundred pictures. Some of these houses had historic appeal as well as architectural charm — John Alden's house at Duxbury where Priscilla and he lived and died, the Fairbanks house at Dedham, houses at Cohasset and Hingham, Lexington Green, Concord, Salem and Plymouth. Often a turn in the road would bring to view some old patriarch with an indescribable charm that, being indescribable, I shall now proceed to describe. The outstanding feature of these houses is a big, fat central chimney. ''Big" doesn't mean maybe. Even on small houses these chimneys were often five feet square. Many of the chimneys were painted white with a black top. There is a tradition that this color scheme denoted loyalty to the King. I suspect that whether Whig or Tory, the main purpose of the black top was to prevent the white paint from becoming sooted. As old houses were heated entirely by open fireplaces, these chimneys would frequently have six flues. When these flues are in groups with divisions showing on the surface they are called ''clustered" or "pilastered." Most of them are plain rectangles and usually of brick or plaster. These chimneys ran straight down from the roof through the centre of the house to the cellar or foundations. The result was that when you entered the front door, you ran, "spang" into the chimney. That arrangement clearly isn't so good for a house to-day. Neither are the narrow staircases that, in two story houses, wind around this chimney. Houses of this type must not be confused with larger houses built later. They are the farm-houses of the period from 1650 to 1750. They frequently had a string of outbuildings, woodsheds, summer kitchens, corn cribs, wagon houses, barns, etc. hanging on like the tail to a kite. The charm of these rambling outbuildings is one of the attractions of New England houses even if it does tell the story of what is sometimes erroneously called a "good," old-fashioned winter.

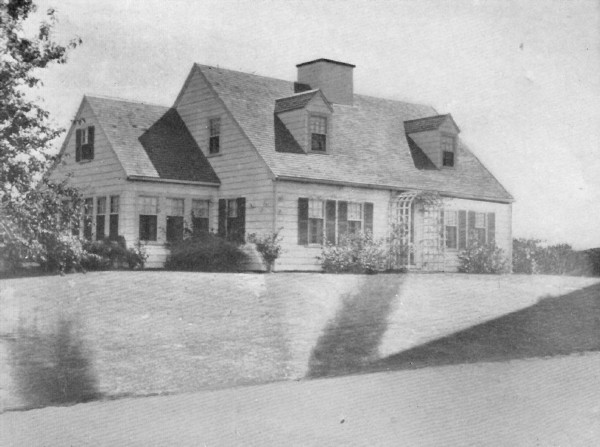

Two Old Houses which show the Symmetry effected by a Central Chimney whether on a Mansion or a Cottage.

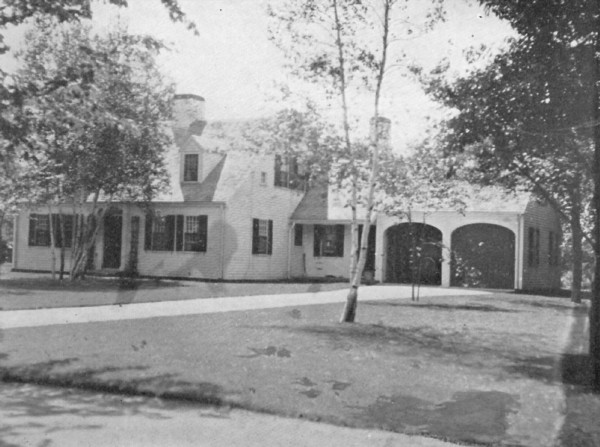

This Man thoroughly believed in a Big Central Chimney. A Modern Reproduction which just misses the desired effect.

A modern Reproduction built in 1929.

There was a typical arrangement of windows, five on the second floor, and four and an entrance door downstairs. The second floor windows were usually placed directly above those of the floor below. When this rule was departed from, the house looked cockeyed. The front door rarely had much of a porch — merely a hooded entrance. The entrance door was exactly in the centre of the house. Window panes were invariably small. Big ones cost money. Frequently there would be twenty-four lights to a pair of sash. Sometimes there were more panes in the upper sash, sometimes more in the lower. These houses were invariably built close to the ground. The main house was almost always a square or rectangular box. There seems to be some definite harmony of proportion that gives houses of this type a refreshing note of symmetry. Experts can construct a whole house of this type merely if given a few key measurements much as a paleontologist can restore a Dinosaur or sabre-toothed tiger for a museum from a piece of jaw-bone and a couple of toe joints. Many of these houses were unpainted. The shingles in this climate weather to a gorgeous brown the color of a chestnut. Down Cape Cod way, they sometimes shingled the front and clapboarded the sides. Others did just the opposite. Houses frequently had solid wooden shutters downstairs, and blinds with fixed or rigid louvres for the second floor. Most shutters were painted green. Some were pink or blue. There are hundreds of houses from Salem to the tip of Cape Cod bearing a family resemblance to the type I am describing. The floor plan was exceedingly simple. Just a room on each side of the central chimney with a kitchen sometimes partly in an extension. There were cupboards and closets everywhere. The closet under the staircase was usually equipped with a batten door with hand-forged hardware and H.L. hinges. Rim locks or latches are a common hardware detail. It will always remain a mystery to me how our Puritan forefathers were able to get huge beds and chests up the narrow stairs. Perhaps they laid the floor and then built the house around the furniture. The frames of old houses are invariably heavy with morticed and tenoned joints pegged together to defy the elements. A tenon is a projecting piece of wood (from the French ''tenir" to hold.) A mortice is a carefully cut slot made to receive it. A peg — well that's what it is — a peg. There is enough lumber in the frame of an old house to build two or three modern houses of the same size. And the sturdy old oak they used would make a modern 2x4 hemlock or fir stud roll over and play dead almost in a single generation. Wide planks laid random widths and either nailed down with projecting wrought-iron nail heads, or pinned in place with wooden pegs, formed the floor. Early settlers had so much to do with the sea that their floors quite naturally resembled the deck of a ship. To-day architects call planking of this early type, "roughneck" floors. The under side of these floors, in two story houses, formed the ceiling of the first floor, giving a beamed ceiling effect that has since been adapted to hotel grill rooms. Frequently sidewall partitions were also of wood. In the John Alden house at Duxbury, there is a clear white pine board in a side wall twenty-nine inches wide. Try to find such a board in your local lumber yard to-day. As a forerunner of modern insulation, the space between the inner and outer walls of the house was sometimes filled with soft home-made brick laid up in clay mortar. Often the insulation was just clay, wattle or sea weed. There was a minimum of masonry in these houses because, in the early days, lime which is a necessary ingredient of mortar, was exceedingly scarce and wood was plentiful and cheap. They even made their chimneys of wood at first, laid up cob-house style and daubed with clay. But after one-third of the houses of the Plymouth Colony were destroyed by fire during the first two winters, someone conceived the heaven-born idea that logs and clay weren't such good materials to make a chimney with after all. In some of the earliest houses which have survived nearly three hundred years, the second floor projected beyond the first floor side wall. In this overhang type, the projection was ornamented with a hanging wooden ball, a bracket or a crude pineapple shape. Such houses are rarely found to-day. The prevailing type is characterized by a note of simplicity and freedom from ornamentation which gives them their greatest charm. They also create the impression that there isn't a wasted inch of space and this is a fact. Gingerbread work and gew-gaws hadn't begun to cast their blight upon the land in early Colonial days. The Greek revival in architecture hadn't arrived. Neither had the ready-cut boys or the people who get their ideas of the kind of house they want from a Pullman car — I mean from the car itself, not merely by looking out of its windows. What quality makes these early houses so admired to-day? How could local carpenters build them without plans or blue prints and preserve a simplicity of form that even to-day stands as a perfect example of restraint? These men never heard of Beaux Arts. They would probably have thought ''renaissance" was the name of a fish. The answer seems to be that there was but little attempt at embellishment because gewgaws cost money and time. What to them was a necessity has since become (to some people at least) a virtue. There is a certain aloofness about these venerable houses that the most noble bestuccoed and red-tiled house on your street can't approach. Early American houses are "snooty houses." They are distinctly ''high hat," and yet they are the sort of house that compels a tourist whizzing by to turn back for a second look. It must be admitted, however, that early houses weren't always admired. Even Thomas Jefferson, who was an amateur architect himself, referred to the old dormitories of William and Mary as ''rude misshapen piles that resembled a brick kiln." In commenting on early houses he said, ''English architecture is the most wretched I ever saw, not excepting America or even Virginia which is worse than in any other part of America." He then proceeded to design a house for himself. May I be pardoned as a rank iconoclast to remark that I don't consider the result of his efforts — "Monticello" in Virginia — so hot as an example of an improvement over the houses he saw in New England. As late as 1850 or thereabouts, a Philadelphia lady, Mrs. Tuthill, wrote a book called "A History of Architecture." She made the mild comment that she considered those gorgeous old New England churches (like the one restored in Concord, for example, or Old South, in Boston) "outrageous deformities to the eye of taste." She then took a gentle fall out of my pet houses by calling them "wooden enormities." How she must have loved a Mansard roof!

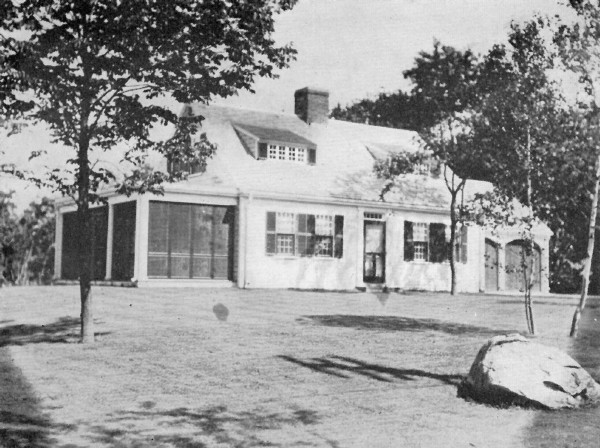

You can't have modern Dormer Windows and preserve the Colonial Flavor.  One of the Central Chimney New England Farm Houses that were photographed and studied before the plans were drawn for the house described in this book.   These two Houses have been remodeled and in the upper one, Dormer Windows added. But a close inspection shows that they are very old.

One reason, other than the scarcity of lime, why the Pilgrims built of wood was because wooden houses were the kind they lived in at home. Early settlers were peasants — the yeomanry of England. Stone mansions were reserved for the nobility until the huge demands of the British navy put oak and other woods at a premium. Then stone cottages began to appear. The Pilgrims probably never dreamed that three hundred years after they landed we would lay claim to noble blood and emblazon all sorts of weird crests and heraldry on our limousines and stationery, in the illusion that really the passengers on the Mayflower were William the Conqueror or Queen Elizabeth and her royal suite, travelling incog for religious reasons. It is natural that the generation immediately following any period of development may look upon those advances in art as crude and old fashioned. Possibly our opinion of Victorian furniture and architecture may be wrong. However, I never expect to see a book written extolling the merits of the Mansard roof house of Mrs. Tuthill's time with its cupolas and gingerbread work and iron dogs on the lawn. Her book is now out of print. It is my profound wish (to which my publishers shout a loud, ''amen") that a book questioning the lady's opinion of those "wooden enormities" may speedily become a best seller. When we speak of an early American house, it really doesn't mean much. There was no type of house at any period of the country's development common to all of the colonies. New England architecture was distinctly different from New Jersey or Virginia. The Dutch who settled in New York and New Jersey built gambrel roofed stone houses. Further south, they went in for porches and smaller chimneys. An architect can place the general location of a Colonial house just by looking at a picture of it. So can you, even with superficial study. Any old house is charming to most people. This appreciation, so universal to-day, began to crystallize with Hawthorne's ''House of Seven Gables," and Longfellow's "Wayside Inn" at Sudbury, Massachusetts, which is still standing, now being owned by Mr. Henry Ford. To me, an exceedingly important element in the charm of old farm-houses is the chimney. Artists seem to have that instinctive feeling too. When an artist sets out to make a picture of "home, sweet home," nine times out of ten his little vine-covered cottage will have one of those fat chimneys located right in the middle of the roof. Why is this? Artists certainly don't see central-chimney houses where they live, unless they happen to live in New England. One can travel from New York to California and scarcely see one. It seems to be an instinct that such a house furnishes the right scenery for sun-bonneted country maids leaning on the fence, or sad eyed mothers gazing down the road awaiting the return of little Freddie from the wicked city. The big chimney is what actors call ''sure fire hokum." It always gets a hand. Authorities say that there is a strong Georgian influence manifested in New England houses (George I-IV, 1714-1830). It is only natural that English tradition should be strong until the blight of Greek affectation and the so-called ''rococo" trend tried to make a woodshed look like a Grecian temple. It is generally supposed that the Puritans lived under conditions of great discomfort. So they did for a while. In a book published in 1654, written by Captain Edward Johnson, the founder of Woburn, Massachusetts, he says, "The English settlers burrow for themselves, their first shelter, under some hillside, casting the earth aloft on timbers. Yet in these poor wigwams they sing psalms till they can provide themselves houses." That is probably exactly what we should do to-day under similar circumstances, except that we might cut out the singing. But if you picture our ancestors slowly freezing for very long in some such Eskimo igloo as this, read what he also said about conditions a little later: "The Lord hath been pleased to turn all the wigwams, huts and hovels the English dwelt in at their first coming into orderly, fair and well built houses, well furnished, many of them." I wonder what he would have said about the present homes of some of their descendants, living in kitchenette tenements where you walk up four flights of stairs to look out on a garbage dump, and pay a landlord eighty dollars a month for the privilege. It is evident that the early settlers weren't satisfied very long with homes where a pack of red-eyed wolves glared through the roof at you when you went to call on your best girl. It did not take the Priscillas of that day long to notice that the easy working qualities of white pine wouldn't make the building of a real house such a whale of a job after all. I can imagine her saying: "John, I am getting pretty well fed up on this shack with clay daubs and a nasty old roof that leaks a stream every time we have a shower. How about getting busy this spring and starting a real house like the Jones'?" Probably one of the first colonists to say this was Mrs. Fairbanks of Dedham, Massachusetts. The Fairbanks house is said to be the oldest Colonial house standing in America ( 1636) . This statement, however, will promptly be challenged by the rooters for the Whitfield house in Guilford, Connecticut, and the Roger Williams house in Salem. But if the date is right, it was built only sixteen years after the Mayflower Society was founded, which now gives bridge luncheons to preserve these priceless relics. The Fairbanks house is really a handsome house to-day. Its sweeping graceful lines would be a credit to any community. It is a million miles removed from an Indian wigwam. By the end of 1700 there were many fine old houses. Some of them have elaborate carvings in stair rails, newels and entrances. It is little short of amazing to think that much of this work was done by men who had the most meager training in the fine arts. They worked with the crudest kind of chisels, moulding planes and other tools. It certainly gives a modern house-builder a pain to pay a wood-butcher $12. a day, who can scarcely drive a nail without mashing his thumb. Think of the skill of men who could fashion those urns and fanlights and paneled rooms and fireplaces. They worked with nails made in a local blacksmith shop. They prepared their glue from the parings of horses' hoofs. They got out their own timber from logs. Yet, so cheap was labor, houses did not cost much then. In 1640, according to an old account book, John Davys, a joiner, contracted to build one for William Rix, a weaver, for 21 pounds. That is about $105. The framing timber of old houses was scored and hewn by hand. Except for axe marks some of it is just about as true and square as if it came from a saw mill. Where is the man to-day who can jump on a fallen oak and with a broad axe, modeled after the one they used on the neck of Charles the First, work a log into shape? Do you think a golf stroke is hard to acquire? How about taking your stance on a round stick and with a broad axe as sharp as a razor make a few mashie niblick chip shots, cutting out a piece of hard oak with every shot? Keep your eye on the log, or the divots you take may be several of your toes. To build the crudest kind of houses must have required skill far beyond that of carpenters to-day. There was no sawed lumber at first. But there were no better carpenters in the world than the English carpenters of the seventeenth century. So far as I know, there are no better even yet. How can any of the descendants of such men content themselves with a hideous two-family house on a back street, a Greek delicatessen on one side, and a galvanized iron garage on the other — and call it a home? There must be some answer. As I can't think of one, however, let's blame it on prohibition. In these, more or less. United States, we have the right to build and live in any kind of a house we wish. An architectural crime isn't recognized by the courts. Any nation that complacently looks, on, while bill-boards multiply on every roadside to mar the face of nature, shouldn't be too fussy about a few trick houses. We can go as far as we like, but those old codgers of 1650-1750 weren't fooled much. They just seemed to know that squatty houses with fat chimneys and green blinds were pretty good to look at and live in, so they mostly built houses of that type, and called it a day. |