| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2007 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER I

THE START The Vale

of Kashmir is too well

known to require description. It is the

'happy hunting-ground' of the Anglo-Indian sportsman and tourist, the

resort of

artists and invalids, the home of pashm

shawls and exquisitely embroidered fabrics, and the land of Lalla

Rookh. Its

inhabitants, chiefly Moslems, infamously governed by Hindus, are a

feeble race,

attracting little interest, valuable to travellers as 'coolies' or

porters, and

repulsive to them from the mingled cunning and obsequiousness which

have been

fostered by ages of oppression. But even for them there is the dawn of

hope,

for the Church Missionary Society has a strong medical and educational

mission

at the capital, a hospital and dispensary under the charge of a lady

M.D. have

been opened for women, and a capable and upright 'settlement officer,'

lent by

the Indian Government, is investigating the iniquitous land

arrangements with a

view to a just settlement. I left the

Panjāb railroad system at

Rawul Pindi, bought my camp equipage, and travelled through the grand

ravines

which lead to Kashmir or the Jhelum Valley by hill-cart, on horseback,

and by

house-boat, reaching Srinagar at the end of April, when the velvet

lawns were

at their greenest, and the foliage was at its freshest, and the

deodar-skirted

mountains which enclose this fairest gem of the Himalayas still wore

their

winter mantle of unsullied snow. Making Srinagar my headquarters, I

spent two

months in travelling in Kashmir, half the time in a native house-boat

on the

Jhelum and Pohru rivers, and the other half on horseback, camping

wherever the

scenery was most attractive. By the

middle of June mosquitos were

rampant, the grass was tawny, a brown dust haze hung over the valley,

the

camp-fires of a multitude glared through the hot nights and misty

moonlight of

the Munshibagh, English tents dotted the landscape, there was no

mountain,

valley, or plateau, however remote, free from the clatter of English

voices and

the trained servility of Hindu servants, and even Sonamarg, at an

altitude of

8,000 feet and rough of access, had capitulated to lawn-tennis. To a traveller this Anglo-Indian hubbub was

intolerable, and I left Srinagar and many kind friends on June 20 for

the

uplifted plateaux of Lesser Tibet. My

party consisted of myself, a thoroughly competent servant and passable

interpreter, Hassan Khan, a Panjābi; a seis,

of whom the less that is said the better; and Mando, a Kashmiri lad, a

common

coolie, who, under Hassan Khan's training, developed into an efficient

travelling servant, and later into a smart khītmatgar. Gyalpo, my

horse, must not be forgotten

— indeed, he cannot be, for he left the marks of his heels or teeth on

every

one. He was a beautiful creature,

Badakshani bred, of Arab blood, a silver-grey, as light as a greyhound

and as

strong as a cart-horse. He was higher

in the scale of intellect than any horse of my acquaintance. His cleverness at times suggested reasoning

power, and his mischievousness a sense of humour. He

walked five miles an hour, jumped like a deer, climbed like a yak, was strong and steady in

perilous

fords, tireless, hardy, hungry, frolicked along ledges of precipices

and over

crevassed glaciers, was absolutely fearless, and his slender legs and

the use

he made of them were the marvel of all. He was an enigma to the end. He was quite untamable, rejected all

dainties with indignation, swung his heels into people's faces when

they went

near him, ran at them with his teeth, seized unwary passers-by by their

kamar bands, and

shook them as a dog

shakes a rat, would let no one go near him but Mando, for whom he

formed at first

sight a most singular attachment, but kicked and struck with his

forefeet, his

eyes all the time dancing with fun, so that one could never decide

whether his

ceaseless pranks were play or vice. He was always tethered in front of

my tent

with a rope twenty feet long, which left him practically free; he was

as good

as a watchdog, and his antics and enigmatical savagery were the life

and terror

of the camp. I was never weary of

watching him, the curves of his form were so exquisite, his movements

so lithe and

rapid, his small head and restless little ears so full of life and

expression,

the variations in his manner so frequent, one moment savagely attacking

some

unwary stranger with a scream of rage, the next laying his lovely head

against

Mando's cheek with a soft cooing sound and a childlike gentleness. When he was attacking anybody or frolicking,

his movements and beauty can only be described by a phrase of the

Apostle

James, 'the grace of the fashion of it.' Colonel

Durand, of Gilgit celebrity, to whom I am indebted

for many

other kindnesses, gave him to me in exchange for a cowardly, heavy

Yarkand

horse, and had previously vainly tried to tame him.

His wild eyes were like those of a seagull.

He had no kinship with humanity. In

addition, I had as escort an

Afghan or Pathan, a soldier of the Maharajah's irregular force of

foreign

mercenaries, who had been sent to meet me when I entered Kashmir. This man, Usman Shah, was a stage ruffian in

appearance. He wore a turban of

prodigious height ornamented with poppies or birds' feathers, loved

fantastic

colours and ceaseless change of raiment, walked in front of me carrying

a big

sword over his shoulder, plundered and beat the people, terrified the

women,

and was eventually recognised at Leh as a murderer, and as great a

ruffian in

reality as he was in appearance. An

attendant of this kind is a mistake. The

brutality and rapacity he exercises naturally make the

people

cowardly or surly, and disinclined to trust a traveller so accompanied. Finally, I

had a Cabul tent, 7 ft. 6

in. by 8 ft. 6 in., weighing, with poles and iron pins, 75 lbs., a

trestle bed

and cork mattress, a folding table and chair, and an Indian dhurrie as a carpet. My servants had a tent 5 ft. 6 in. square, weighing only 10 lbs., which served as a shelter tent for me during the noonday halt. A kettle, copper pot, and frying pan, a few enamelled iron table equipments, bedding, clothing, working and sketching materials, completed my outfit. The servants carried wadded quilts for beds and bedding, and their own cooking utensils, unwillingness to use those belonging to a Christian being nearly the last rag of religion which they retained. The only stores I carried were tea, a quantity of Edwards' desiccated soup, and a little saccharin. The 'house,' furniture, clothing, &c., were a light load for three mules, engaged at a shilling a day each, including the muleteer. Sheep, coarse flour, milk, and barley were procurable at very moderate prices on the road.  The Start from Srinagar Leh, the

capital of Ladakh or Lesser

Tibet, is nineteen marches from Srinagar, but I occupied twenty-six

days on the

journey, and made the first 'march' by water, taking my house-boat to

Ganderbal, a few hours from Srinagar, via the Mar Nullah and Anchar

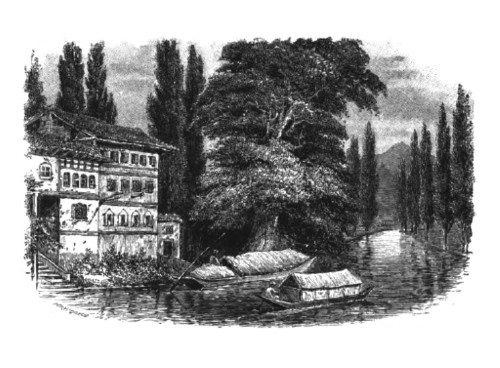

Lake. Never had this Venice of the

Himalayas, with

a broad rushing river for its high street and winding canals for its

back

streets, looked so entrancingly beautiful as in the slant sunshine of

the late

June afternoon. The light fell brightly

on the river at the Residency stairs where I embarked, on perindas and state barges, with

their

painted arabesques, gay canopies, and 'banks' of thirty and forty

crimson-clad,

blue-turbaned, paddling men; on the gay facade and gold-domed temple of

the

Maharajah's Palace, on the massive deodar bridges which for centuries

have

defied decay and the fierce flood of the Jhelum, and on the quaintly

picturesque wooden architecture and carved brown lattice fronts of the

houses

along the swirling waterway, and glanced mirthfully through the dense

leafage

of the superb planes which overhang the dark-green water.

But the mercury was 92° in the shade and the

sun-blaze terrific, and it was a relief when the boat swung round a

corner, and

left the stir of the broad, rapid Jhelum for a still, narrow, and

sharply

winding canal, which intersects a part of Srinagar lying between the

Jhelum and

the hill-crowning fort of Hari Parbat. There

the shadows were deep, and chance lights alone fell

on the red

dresses of the women at the ghats, and on the shaven, shiny heads of

hundreds

of amphibious boys who were swimming and aquatically romping in the

canal,

which is at once the sewer and the water supply of the district. Several hours were spent in a slow and tortuous progress through scenes of indescribable picturesqueness—a narrow waterway spanned by sharp-angled stone bridges, some of them with houses on the top, or by old brown wooden bridges festooned with vines, hemmed in by lofty stone embankments into which sculptured stones from ancient temples are wrought, on the top of which are houses of rich men, fancifully built, with windows of fretwork of wood, or gardens with kiosks, and lower embankments sustaining many-balconied dwellings, rich in colour and fantastic in design, their upper fronts projecting over the water and supported on piles. There were gigantic poplars wreathed with vines, great mulberry trees hanging their tempting fruit just out of reach, huge planes overarching the water, their dense leafage scraping the mat roof of the boat; filthy ghats thronged with white-robed Moslems performing their scanty religious ablutions; great grain boats heavily thatched, containing not only families, but their sheep and poultry; and all the other sights of a crowded Srinagar waterway, the houses being characteristically distorted and out of repair. This canal gradually widens into the Anchar Lake, a reedy mere of indefinite boundaries, the breeding-ground of legions of mosquitos; and after the tawny twilight darkened into a stifling night we made fast to a reed bed, not reaching Ganderbal till late the next morning, where my horse and caravan awaited me under a splendid plane-tree.  Camp at Gagangair For the next five days we marched up the Sind Valley, one of the most beautiful in Kashmir from its grandeur and variety. Beginning among quiet rice-fields and brown agricultural villages at an altitude of 5,000 feet, the track, usually bad and sometimes steep and perilous, passes through flower-gemmed alpine meadows, along dark gorges above the booming and rushing Sind, through woods matted with the sweet white jasmine, the lower hem of the pine and deodar forests which ascend the mountains to a considerable altitude, past rifts giving glimpses of dazzling snow-peaks, over grassy slopes dotted with villages, houses, and shrines embosomed in walnut groves, in sight of the frowning crags of Haramuk, through wooded lanes and park-like country over which farms are thinly scattered, over unrailed and shaky bridges, and across avalanche slopes, till it reaches Gagangair, a dream of lonely beauty, with a camping-ground of velvety sward under noble plane-trees. Above this place the valley closes in between walls of precipices and crags, which rise almost abruptly from the Sind to heights of 8,000 and 10,000 feet. The road in many places is only a series of steep and shelving ledges above the raging river, natural rock smoothed and polished into riskiness by the passage for centuries of the trade into Central Asia from Western India, Kashmir, and Afghanistan. Its precariousness for animals was emphasised to me by five serious accidents which occurred in the week of my journey, one of them involving the loss of the money, clothing, and sporting kit of an English officer bound for Ladakh for three months. Above this tremendous gorge the mountains open out, and after crossing to the left bank of the Sind a sharp ascent brought me to the beautiful alpine meadow of Sonamarg, bright with spring flowers, gleaming with crystal streams, and fringed on all sides by deciduous and coniferous trees, above and among which are great glaciers and the snowy peaks of Tilail. Fashion has deserted Sonamarg, rough of access, for Gulmarg, a caprice indicated by the ruins of several huts and of a church. The pure bracing air, magnificent views, the proximity and accessibility of glaciers, and the presence of a kind friend who was 'hutted' there for the summer, made Sonamarg a very pleasant halt before entering upon the supposed seventies of the journey to Lesser Tibet. The five days' march, though propitious and full of the charm of magnificent scenery, had opened my eyes to certain unpleasantnesses. I found that Usman Shah maltreated the villagers, and not only robbed them of their best fowls, but requisitioned all manner of things in my name, though I scrupulously and personally paid for everything, beating the people with his scabbarded sword if they showed any intention of standing upon their rights. Then I found that my clever factotum, not content with the legitimate 'squeeze' of ten per cent., was charging me double price for everything and paying the sellers only half the actual price, this legerdemain being perpetrated in my presence. He also by threats got back from the coolies half their day's wages after I had paid them, received money for barley for Gyalpo, and never bought it, a fact brought to light by the growing feebleness of the horse, and cheated in all sorts of mean and plausible ways, though I paid him exceptionally high wages, and was prepared to 'wink' at a moderate amount of dishonesty, so long as it affected only myself. It has a lowering influence upon one to live in a fog of lies and fraud, and the attempt to checkmate a fraudulent Asiatic ends in extreme discomfiture.  Sonamarg I left

Sonamarg late on a lovely

afternoon for a short march through forest-skirted alpine meadows to

Baltal,

the last camping-ground in Kashmir, a grassy valley at the foot of the

Zoji La,

the first of three gigantic steps by which the lofty plateaux of

Central Asia

are attained. On the road a large affluent

of the Sind, which tumbles down a pine-hung gorge in broad sheets of

foam, has

to be crossed. My seis,

a rogue,

was either half-witted or pretended to be so, and, in spite of orders

to the

contrary, led Gyalpo upon a bridge at a considerable height, formed of

two

poles with flat pieces of stone laid loosely over them not more than a

foot

broad. As the horse reached the middle,

the structure gave a sort of turn, there was a vision of hoofs in air

and a

gleam of scarlet, and Gyalpo, the hope of the next four months, after

rolling

over more than once, vanished among rocks and surges of the wildest

description. He kept his presence of

mind, however, recovered himself, and by a desperate effort got ashore

lower

down, with legs scratched and bleeding and one horn of the saddle

incurably

bent. Mr.

Maconochie of the Panjāb Civil Service,

and Dr. E. Neve of the C. M.

S. Medical Mission in Kashmir, accompanied me from Sonamarg over the

pass, and

that night Mr. M. talked seriously to Usman Shah on the subject of his

misconduct, and with such singular results that thereafter I had little

cause

for complaint. He came to me and said,

'The Commissioner Sahib thinks I give Mem Sahib a great deal of

trouble;' to

which I replied in a cold tone, 'Take care you don't give me any more.' The gist of the Sahib's words was the very

pertinent suggestion that it would eventually be more to his interest

to serve

me honestly and faithfully than to cheat me. Baltal

lies at the feet of a

precipitous range, the peaks of which exceed Mont Blanc in height. Two gorges unite there. There

is not a hut within ten miles. Big

camp-fires blazed. A few shepherds lay

under the shelter of a

mat screen. The silence and solitude

were most impressive under the frosty stars and the great Central Asian

barrier. Sunrise the following morning

saw us on the way up a huge gorge with nearly perpendicular sides, and

filled

to a great depth with snow. Then came

the Zoji La, which, with the Namika La and the Fotu La, respectively

11,300,

13,000, and 13,500 feet, are the three great steps from Kashmir to the

Tibetan

heights. The two latter passes present

no difficulties. The Zoji La is a

thoroughly severe pass, the worst, with the exception perhaps of the

Sasir, on

the Yarkand caravan route. The track,

cut, broken, and worn on the side of a wall of rock nearly 2,000 feet

in abrupt

elevation, is a series of rough narrow zigzags, rarely, if ever, wide

enough

for laden animals to pass each other, composed of broken ledges often

nearly

breast high, and shelving surfaces of abraded rock, up which animals

have to leap

and scramble as best they may. Trees and

trailers drooped over the

path, ferns and lilies bloomed in moist recesses, and among myriads of

flowers

a large blue and cream columbine was conspicuous by its beauty and

exquisite

odour. The charm of the detail tempted

one to linger at every turn, and all the more so because I knew that I

should

see nothing more of the grace and bounteousness of Nature till my

projected

descent into Kulu in the late autumn. The

snow-filled gorge on whose abrupt side the path hangs,

the Zoji La

(Pass), is geographically remarkable as being the lowest depression in

the

great Himalayan range for 300 miles; and by it, in spite of infamous

bits of

road on the Sind and Suru rivers, and consequent losses of goods and

animals,

all the traffic of Kashmir, Afghanistan, and the Western Panjāb finds its way into Central Asia.

It was too early in the season, however, for

more than a few enterprising caravans to be on the road. The last

look upon Kashmir was a

lingering one. Below, in shadow, lay

the Baltal camping-ground, a lonely deodar-belted flowery meadow, noisy

with

the dash of icy torrents tumbling down from the snowfields and glaciers

upborne

by the gigantic mountain range into which we had penetrated by the Zoji

Pass. The valley, lying in shadow at

their base, was a dream of beauty, green as an English lawn, starred

with white

lilies, and dotted with clumps of trees which were festooned with red

and white

roses, clematis, and white jasmine. Above

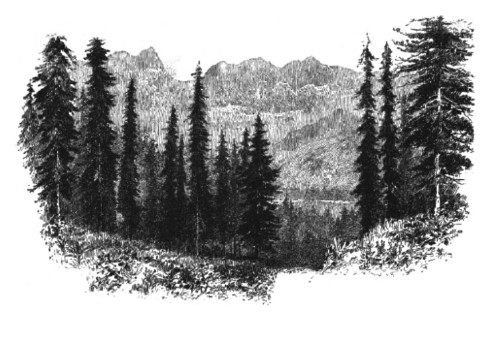

the hardier deciduous trees appeared the Pinus excelsa, the silver fir,

and the spruce;

higher yet the stately grace of the deodar clothed the hillsides; and

above the

forests rose the snow mountains of Tilail, pink in the sunrise. High above the Zoji, itself 11,500 feet in

altitude, a mass of grey and red mountains, snow-slashed and snow-

capped, rose

in the dewy rose-flushed atmosphere in peaks, walls, pinnacles, and

jagged

ridges, above which towered yet loftier summits, bearing into the

heavenly blue

sky fields of unsullied snow alone. The

descent on the Tibetan side is slight and gradual.

The character of the scenery undergoes an abrupt change. There are no more trees, and the large

shrubs which for a time take their place degenerate into thorny bushes,

and

then disappear. There were mountains

thinly clothed with grass here and there, mountains of bare gravel and

red

rock, grey crags, stretches of green turf, sunlit peaks with their

snows, a

deep, snow-filled ravine, eastwards and beyond a long valley filled

with a

snowfield fringed with pink primulas; and that was CENTRAL ASIA. We halted

for breakfast, iced our

cold tea in the snow, Mr. M. gave a final charge to the Afghan, who

swore by

his Prophet to be faithful, and I parted from my kind escorts with much

reluctance, and started on my Tibetan journey, with but a slender stock

of

Hindustani, and two men who spoke not a word of English.

On that day's march of fourteen miles there

is not a single hut. The snowfield

extended for five miles, from ten to seventy feet deep, much crevassed,

and

encumbered with avalanches. In it the

Dras, truly 'snow-born,' appeared, issuing from a chasm under a blue

arch of

ice and snow, afterwards to rage down the valley, to be forded many

times or

crossed on snow bridges. After walking

for some time, and getting a bad fall down an avalanche slope, I

mounted

Gyalpo, and the clever, plucky fellow frolicked over the snow, smelt

and leapt

crevasses which were too wide to be stepped over, put his forelegs

together and

slid down slopes like a Swiss mule, and, though carried off his feet in

a ford

by the fierce surges of the Dras, struggled gamely to shore. Steep grassy hills, and peaks with gorges

cleft by the thundering Dras, and stretches of rolling grass succeeded

each

other. Then came a wide valley mostly covered with stones brought down

by

torrents, a few plots of miserable barley grown by irrigation, and

among them

two buildings of round stones and mud, about six feet high, with flat

mud

roofs, one of which might be called the village, and the other the

caravanserai. On the village roof were

stacks of twigs and of the dried dung of animals, which is used for

fuel, and

the whole female population, adult and juvenile, engaged in picking

wool. The people of this village of

Matayan are

Kashmiris. As I had an hour to wait for

my tent, the women descended and sat in a circle round me with a

concentrated

stare. They asked if I were dumb, and

why I wore no earrings or necklace, their own persons being loaded with

heavy

ornaments. They brought children

afflicted with skin- diseases, and asked for ointment, and on hearing

that I

was hurt by a fall, seized on my limbs and shampooed them energetically

but not

undexterously. I prefer their

sociability to the usual chilling aloofness of the people of Kashmir. The Serai

consisted of several dark

and dirty cells, built round a blazing piece of sloping dust, the only

camping-ground, and under the entrance two platforms of animated earth,

on

which my servants cooked and slept. The

next day was Sunday, sacred to a halt; but there was no fodder for the

animals,

and we were obliged to march to Dras, following, where possible, the

course of

the river of that name, which passes among highly-coloured and

snow-slashed

mountains, except in places where it suddenly finds itself pent between

walls

of flame- coloured or black rock, not ten feet apart, through which it

boils

and rages, forming gigantic pot-holes. With

every mile the surroundings became more markedly of

the Central

Asian type. All day long a white,

scintillating sun blazes out of a deep blue, rainless, cloudless sky. The air is exhilarating. The

traveller is conscious of

daily-increasing energy and vitality. There

are no trees, and deep crimson roses along torrent

beds are the

only shrubs. But for a brief fortnight

in June, which chanced to occur during my journey, the valleys and

lower slopes

present a wonderful aspect of beauty and joyousness.

Rose and pale pink primulas fringe the margin of the snow,

the

dainty Pedicularis tubiflora

covers moist spots with its mantle of gold; great yellow and white, and

small

purple and white anemones, pink and white dianthus, a very large

myosotis,

bringing the intense blue of heaven down to earth, purple orchids by

the water,

borage staining whole tracts deep blue, martagon lilies, pale green

lilies

veined and spotted with brown, yellow, orange, and purple vetches,

painter's

brush, dwarf dandelions, white clover, filling the air with fragrance,

pink and

cream asters, chrysanthemums, lychnis, irises, gentian, artemisia, and

a

hundred others, form the undergrowth of millions of tall Umbelliferae

and

Compositae, many of them peach-scented and mostly yellow.

The wind is always strong, and the millions

of bright corollas, drinking in the sun-blaze which perfects all too

soon their

brief but passionate existence, rippled in broad waves of colour with

an almost

kaleidoscopic effect. About the

eleventh march from Srinagar, at Kargil, a change for the worse occurs,

and the

remaining marches to the capital of Ladakh are over blazing gravel or

surfaces

of denuded rock, the singular Caprifolia

horrida, with its dark-green mass of wavy ovate leaves on

trailing

stems, and its fair, white, anemone- like blossom, and the graceful Clematis orientalis, the only

vegetation. Crossing a

raging affluent of the

Dras by a bridge which swayed and shivered, the top of a steep hill

offered a

view of a great valley with branches sloping up into the ravines of a

complexity of mountain ranges, from 18,000 to 21,000 feet in altitude,

with

glaciers at times descending as low as 11,000 feet in their hollows. In consequence of such possibilities of

irrigation, the valley is green with irrigated grass and barley, and

villages

with flat roofs scattered among the crops, or perched on the spurs of

flame-coloured mountains, give it a wild cheerfulness.

These Dras villages are inhabited by hardy

Dards and Baltis, short, jolly-looking, darker, and far less handsome

than the

Kashmiris; but, unlike them, they showed so much friendliness, as well

as

interest and curiosity, that I remained with them for two days,

visiting their

villages and seeing the 'sights' they had to show me, chiefly a great

Sikh

fort, a yak bull, the zho, a hybrid, the interiors of

their

houses, a magnificent view from a hilltop, and a Dard dance to the

music of

Dard reed pipes. In return I sketched

them individually and collectively as far as time allowed, presenting

them with

the results, truthful and ugly. I

bought a sheep for 2s. 3d., and regaled the camp upon

it, the

three which were brought for my inspection being ridden by boys astride. The

evenings in the Dras valley were

exquisite. As soon as the sun went

behind the higher mountains, peak above peak, red and snow- slashed,

flamed

against a lemon sky, the strong wind moderated into a pure stiff

breeze,

bringing up to camp the thunder of the Dras, and the musical tinkle of

streams

sparkling in absolute purity. There was

no more need for boiling and filtering. Icy

water could be drunk in safety from every crystal

torrent. Leaving

behind the Dras villages and

their fertility, the narrow road passes through a flaming valley above

the

Dras, walled in by bare, riven, snow-patched peaks, with steep

declivities of

stones, huge boulders, decaying avalanches, walls and spires of rock,

some

vermilion, others pink, a few intense orange, some black, and many

plum-coloured, with a vitrified look, only to be represented by purple

madder. Huge red chasms with

glacier-fed torrents, occasional snowfields, intense solar heat

radiating from

dry and verdureless rock, a ravine so steep .and narrow that for miles

together

there is not space to pitch a five-foot tent, the deafening roar of a

river

gathering volume and fury as it goes, rare openings, where willows are

planted

with lucerne in their irrigated shade, among which the traveller camps

at

night, and over all a sky of pure, intense blue purpling into starry

night,

were the features of the next three marches, noteworthy chiefly for the

exchange of the thundering Dras for the thundering Suru, and for some

bad

bridges and infamous bits of road before reaching Kargil, where the

mountains

swing apart, giving space to several villages. Miles

of alluvium are under irrigation there, poplars,

willows, and

apricots abound, and on some damp sward under their shade at a great

height I

halted for two days to enjoy the magnificence of the scenery and the

refreshment of the greenery. These

Kargil villages are the capital of the small State of Purik, under the

Governorship of Baltistan or Little Tibet, and are chiefly inhabited by

Ladakhis

who have become converts to Islam. Racial characteristics, dress, and

manners

are everywhere effaced or toned down by Mohammedanism, and the chilling

aloofness and haughty bearing of Islam were very pronounced among these

converts. The daily

routine of the journey was

as follows: By six a.m. I sent on a

coolie carrying the small tent and lunch basket to await me half-way. Before seven I started myself, with Usman

Shah in front of me, leaving the servants to follow with the caravan. On reaching the shelter tent I halted for

two hours, or till the caravan had got a good start after passing me. At the end of the march I usually found the

tent pitched on irrigated ground, near a hamlet, the headman of which

provided

milk, fuel, fodder, and other necessaries at fixed prices.

'Afternoon tea' was speedily prepared, and

dinner, consisting of roast meat and boiled rice, was ready two hours

later.

After dinner I usually conversed with the headman on local interests,

and was

in bed soon after eight. The servants

and muleteers fed and talked till nine, when the sound of their

'hubble-bubbles' indicated that they were going to sleep, like most

Orientals,

with their heads closely covered with their wadded quilts.

Before starting each morning the account was

made out, and I paid the headman personally. The

vagaries of the Afghan soldier,

when they were not a cause of annoyance, were a constant amusement,

though his

ceaseless changes of finery and the daily growth of his baggage

awakened grave

suspicions. The swashbuckler marched four miles an hour in front of me

with a

swinging military stride, a large scimitar in a heavily ornamented

scabbard

over his shoulder. Tanned socks and

sandals, black or white leggings wound round from ankle to knee with

broad

bands of orange or scarlet serge, white cambric knickerbockers, a white

cambric

shirt, with a short white muslin frock with hanging sleeves and a

leather

girdle over it, a red-peaked cap with a dark-blue pagri wound round it, with one

end hanging over his back,

earrings, a necklace, bracelets, and a profusion of rings, were his

ordinary

costume; and in his girdle he wore a dirk and a revolver, and suspended

from it

a long tobacco pouch made of the furry skin of some animal, a large

leather

purse, and etceteras. As the days went

on he blossomed into blue and white muslin with a scarlet sash, wore a

gold

embroidered peak and a huge white muslin turban, with much change of

ornaments,

and appeared frequently with a great bunch of poppies or a cluster of

crimson

roses surmounting all. His headgear was

colossal. It and the head together must

have been fully a third of his total height. He was a most fantastic

object,

and very observant and skilful in his attentions to me; but if I had

known what

I afterwards knew, I should have hesitated about taking these long

lonely

marches with him for my sole attendant. Between

Hassan Khan and this Afghan violent hatred and

jealousy existed. I have

mentioned roads, and my road

as the great caravan route from Western India into Central Asia. This is a fitting time for an explanation. The traveller who aspires to reach the

highlands of Tibet from Kashmir cannot be borne along in a carriage or

hill-cart. For much of the way he is limited to a foot pace, and if he

has

regard to his horse he walks down all rugged and steep descents, which

are

many, and dismounts at most bridges. By

'roads' must be understood bridle-paths, worn by traffic alone across

the

gravelly valleys, but elsewhere constructed with great toil and

expense, as

Nature compels, the road-maker to follow her lead, and carry his track

along

the narrow valleys, ravines, gorges, and chasms which she has marked

out for

him. For miles at a time this road has

been blasted out of precipices from 1,000 feet to 3,000 feet in depth,

and is

merely a ledge above a raging torrent, the worst parts, chiefly those

round

rocky projections, being 'scaffolded,' i.e. poles are lodged

horizontally among

the crevices of the cliff, and the roadway of slabs, planks, and

brushwood, or

branches and sods, is laid loosely upon them. This

track is always amply wide enough for a loaded beast,

but in many

places, when two caravans meet, the animals of one must give way and

scramble

up the mountain-side, where foothold is often perilous, and always

difficult. In passing a caravan near

Kargil my servant's horse was pushed over the precipice by a loaded

mule and

drowned in the Suru, and at another time my Afghan caused the loss of a

baggage

mule of a Leh caravan by driving it off the track.

To scatter a caravan so as to allow me to pass in solitary

dignity he regarded as one of his functions, and on one occasion, on a

very

dangerous part of the road, as he was driving heavily laden mules up

the steep

rocks above, to their imminent peril and the distraction of their

drivers, I

was obliged to strike up his sword with my alpenstock to emphasise my

abhorrence of his violence. The bridges are unrailed, and many of them

are made

by placing two or more logs across the stream, laying twigs across, and

covering these with sods, but often so scantily that the wild rush of

the water

is seen below. Primitive as these

bridges are, they involve great expense and difficulty in the bringing

of long

poplar logs for great distances along narrow mountain tracks by coolie

labour,

fifty men being required for the average log. The

Ladakhi roads are admirable as compared with those of

Kashmir, and

are being constantly improved under the supervision of H. B. M.'s Joint

Commissioner in Leh. Up to

Kargil the scenery, though

growing more Tibetan with every march, had exhibited at intervals some

traces

of natural verdure; but beyond, after leaving the Suru, there is not a

green

thing, and on the next march the road crosses a lofty, sandy plateau,

on which

the heat was terrible—blazing gravel and a blazing heaven, then fiery

cliffs

and scorched hillsides, then a deep ravine and the large village of

Paskim

(dominated by a fort-crowned rock), and some planted and irrigated

acres; then

a narrow ravine and magnificent scenery flaming with colour, which

opens out

after some miles on a burning chaos of rocks and sand,

mountain-girdled, and on

some remarkable dwellings on a steep slope, with religious buildings

singularly

painted. This is Shergol, the first

village of Buddhists, and there I was 'among the Tibetans.' |