|

CHAPTER IX

THE MAID'S HEAD

Norwich

THE first view of Norwich was slightly

disappointing. The twilight was fading rapidly, and in the half-light

the drive in the 'bus to the Maid's Head took us through streets which

looked like any other street in any other city. An electric car which

passed us made the resemblance to more commonplace localities even

stronger.

The Maid's Head, one of the most noted

inns in England, now dignified (or disgraced) by the name of Hotel, is

a judicious mixture of ancient and modern. After a career which

associated its name with some of the most interesting and entertaining

events in the history of Norwich, it was about to pass into the hands

of a brewing company, when it was rescued and put into its present

shape by Mr. Walter Rye, a distinguished antiquarian, who has the

interests of his native city of Norwich very near to his heart. The

fine Tudor office, the bar, and the carved wainscoted smoke-room have

been saved from the vandals and beer-drinkers. The ancient gables look

down through the glass of the roofed-in courtyard, and Queen

Elizabeth's room, with its narrow private stairway, remains in all its

pristine glory.

Queen Elizabeth, as great a lover of

change as Emperor William, if tradition speaks truly, made Norfolk

several visits during her many progresses. In Norfolk her mother's

early youth was passed.

The Maid's Head is full of treasures.

The corridor is hung with charming old prints, and with drawings of

ancient Norwich monuments now destroyed. The bedrooms, in spite of

their modern furniture and electric lights, still show heavy oak beams

across the ceilings, and the inside walls take quaint forms from the

outside gables. The great assembly-room, at present given over to

French cooking and a table d'hote, has witnessed the efforts of

strolling players and the concerts of court musicians.

It was in this hall, where we hungry

travellers gathered about a daintily lighted little table to eat with

the vigour of Goths, that the good people of Norwich held a meeting in

1778, to decide whether they should or should not collect money to help

conquer "the American rebels." The Norfolk men, it seems, had, however,

so many relatives and friends among these same rebels, and so little

love for King George, that they decided to refuse the government

pecuniary assistance.

Great feastings went on within these

four walls early in the history of Norwich. In the Paston letters

– and every one who goes to Norfolk must read the Paston

letters – "Ye Mayde's Hede" figures several times.

All the great Norfolk families patronized this hostelry on their

journeys to and from the court in London. The paved courtyard walls

have echoed to the wheels of the lumbering coaches and the hoof-beats

of the stout travelling horses of the Howards, the Oxfords, the

Walpoles, and the Bullens, as they drove in for a halt, a change, or a

night in Norwich before proceeding farther. The heavy oaken iron-barred

doors, still to be seen at the entrance, were hung here earlier in the

inn's history; indeed they were on duty fully a century before Sir John

Paston's time. In the thirteenth or early fourteenth century a robbery

of some pilgrims took place in a chamber of the Mayde's Hede. The

unjust accusation that the victims directed against an innocent girl in

their party brought the landlord before the courts of English justice,

and the innkeeper put up these heavy doors to prevent thieves from

entering in future.

The Maid's Head is a house of

entertainment so full of interest that we each spent a profitable

evening reading the artistic little pamphlet containing its history,

and presented us by the thoughtful management, along with our rooms.

Norwich does not get the attention it

deserves from the tourist. We discovered, the morning following our

arrival, that, in spite of the uninteresting streets on which we had

passed judgment the evening before, this city possessed great charm for

the antiquarian. It is as full of ancient flint churches as if they had

been sprinkled out of a pepper-pot. Many of them are falling rapidly

into a state of utter dilapidation, while others have been well

restored.

The narrow lanes teem with houses of the

most curious sort, with gables of quaint shapes and heavy overhanging

facades, which cluster about the melancholy old churches; and it is to

be feared they will soon all disappear, together with the old lanes and

alleys, which are too narrow to admit of thoroughfare or other than

foot-passengers.

Norwich, too, has a town-crier, but he

is altogether a much more magnificent personage than his Boston

confrere. He is a pompous little man, with a voice and a bell quite out

of proportion to his stature. He hurries from corner to corner with an

air of great mystery and importance, halting only to swing his loud

bell and announce that some noted man has died, or that a church

concert will be given. Dressed in a long blue coat much embellished

with red and gold, a broad gold band around his hat, and gold stripes

down the sides of his trousers, Norwich has cause to be proud of its

town-crier.

Norwich has only within the last year or

so been put upon the itinerary of the well-known tourist agencies. Not

only for its noted cathedral, still enclosed by the great wall

surrounding it in monkish times, but for the mixture of old and new is

this city original and charming. Its position in the centre of a most

interesting county lends additional motives for attraction of visitors.

The cathedral is within a stone's throw

of the Maid's Head. Its beautiful cloisters and splendidly carved

gateways do honour to architects long forgotten, while its tall spire

towers loftily above the many churches in its neighbourhood. Near to

the cathedral, upon Tombland Square, stand many noble and ancient

houses. The most interesting of these is now become an antiquity shop,

and is called the House of the Giants, from two great figures which

support the coping over the entrance porch.

This square of Tombland was the scene of

a horrible explosion in olden times, when an enterprising mayor sought

to celebrate his election in a novel way. Fireworks were then little

understood, and, while endeavouring to entertain his fellow citizens by

a display of rockets, the unfortunate city officer succeeded in killing

several hundred of the spectators.

George Borrow's description of Norwich

is as graphic to-day as when the author of "Lavengro," a native of

Norfolk, first wrote it: "A fine old city," he calls it, "view it from

whatever side you will . . . its thrice twelve churches, its mighty

mound, which, if tradition speaks true, was raised by human hands to

serve as a grave heap for a heathen king." The mound is still topped by

a castle, but one of modern date, while at the bottom, on Saturday,

crowds gather to inspect the fine fat cattle raised on Norfolk's rich

pasturelands, and here offered for sale, and also to buy the handsome

horses trotted about for inspection by the successors of George

Borrow's gipsy friend, Mr. Pentelengro. Great stallions, with their

tails and manes braided up in straw or ribbons, muscular ponies, and

even showy carriage-horses are stabled here by the dealers under the

castle wall. Opposite the horse and cattle markets, through a narrow

street at the foot of the mound, runs the electric tram, at once the

terror and the delight of the Norwich citizen. It is not a formidable

danger, judged from the standpoint of a dweller in New York, and it

winds through narrow and quaintly named streets, along Unthank Road,

Rampant Horse Street, Grape Lane, The Gentleman's Walk, Timber Hill,

and so on to Mousehold Heath, the city's park and pleasure-ground.

Past the antique Guild Hall, it is a

long tram ride to the Dolphin Inn in the ancient hamlet of Heigham, now

a portion of Norwich. This inn was once the country house of Bishop

Hall. It is an enchanting spot for afternoon tea. The river flows away

at the bottom of its garden, a windmill is perched up on a low hill in

the distance, and a charming view of Norwich forms a background.

The Invalid, who boasts a fine taste in

ecclesiastical architecture, rather scorned the cathedral for the sake

of St. Peter Mancroft, the great church on the market-place. We could

hardly force her to leave the rosy-cheeked sexton, with whom she had

lengthy gossips concerning St. Peter's history and rich relics, and she

was amply rewarded by a sight of the fine communion plate, the monument

to Sir Thomas Browne, and the leather money paid the bell-ringers long

ago, and which they could only exchange for beer. We had no chance to

test their powers, but the Invalid assured us, on the authority of the

sexton, that, when the present generation of St. Peter's ringers get

the bells in hand, the famous ringers of Christ Church, Oxford, hide

their diminished heads with shame.

Polly's favourite haunt in Norwich was

the book-shop of Mr. Agas Goose, in Rampant Horse Street. There she

filled her mind with proper information concerning the whole of Norfolk

county, and the best way to see it in the short time we had to spend

there. It was she who decided that we were to visit, of all its famous

country-seats, Blickling Hall, which we surnamed "the beautiful."

"And when are you going to lead us

there?" questioned the Matron, as we sipped coffee and nibbled toast

and coquetted with pink petals of Wiltshire bacon, and discussed our

plans.

"To-day at ten-twenty, if we go by

train. It is an easy ride of ten miles by bicycle, if any one chooses

that method of locomotion," was the prompt reply.

But the longer ride by rail tempted us

in our indolence, and accordingly we "booked" for Aylsham, the railroad

station nearest to Blickling. Aylsham revealed its incontestable charms

as we walked up from its station, by a dear old manor-house, now

vacant, and surrounded by a fine park gone nearly wild.

"How I should like to hire it and write

a story about it," said the Invalid, who never wrote a line in her

life, and whose ideas of the uncertain profits of literature are vague.

This sad-looking brick manor-house, deserted since the last heir

vanished from history, sits in a tangle of wild roses and shrubbery,

and would afford a perfect scene for a novel. At the other end of the

town, as soon as we could manage to get the Invalid and Polly past a

cottage where they hung over the palings wrapt in admiration at the

profusion, size, and colour of some wonderful begonias, we started out,

along the smooth flint Norfolk road lined with fascinating country

houses of ancient make, and between two rows of great elm-trees, to

Anne Bullen's ancestral home. Blickling Hall bursts a bit suddenly on

the view. It looks more French than English, at the end of a grass and

gravelled court, with low stables, as at Fontainebleau, stretching down

on either side of the court to the gate. The entrance to the garden is

through a colonnade, and the like of this garden grows nowhere save in

England. It spreads its beauties on but one side of this fine old Tudor

mansion. The beds, in which each flower which grows is doing its

mightiest to make the sweetness of its scented pleasure felt, are

divided by great, fine clipped walls of box. Nowhere is a richer or

more democratic garden. There the nobles and commons, the great and the

humble ones of the floral kingdom, who, regardless of season, blow and

blossom with all their power. Beyond the great carpet of flowers

stretches for acres a wide demesne of dense groves and long, shady

paths, in which Anne Bullen is said to wander and to wail by night for

her lost home and happiness.

Within the Hall, on the great staircase

which divides at the landing, are two portraits carved in wood. In one

of them, Anne Bullen stands here revealed in all the sprightly charm

which captivated Henry's fickle heart, in spite of her somewhat plain

face. She displays a style, a dash, an entrancing coquetry, which, from

the other pictures we had seen of this unhappy woman, we had never

suspected. In the opposite carving, her daughter, Queen Elizabeth,

stands stiff in a bedizened costume, lacking all the grace of her

mother. About this attractive, homelike mansion everywhere the black

bull of the Bullen family crest is to be seen, either carved in wood or

inlaid in marble. The restorations and the splendid new library on the

garden side are models of the perfect taste of their modern designers.

At the gate of Blickling Hall is a

little inn called the Buckinghamshire Arms. It is one of those inns

which have been lately established in England to discourage the sale of

alcoholic drinks by making it more profitable to the innkeeper to sell

milder beverages. The Buckinghamshire Arms is said to be a very

successful experiment. It is neat, clean, a relic in architecture of

Tudor days, dressed up a little to suit modern times, and there we had

a most excellent luncheon for the price of one shilling each.

Blickling Hall Garden.

The church at Blickling has a fine

marble monument to the memory of the late Marquis of Lothian. Here also

are many relics of the very early days when the church was put up or

the foundations put down. The dates being somewhat effaced, the sexton

makes them as remote as he chooses.

After viewing house and park, we still

had two good hours before train-time, so we strolled along slowly back

to Aylsham. Before us strode three farm labourers, going home after

hoeing in a field, – a father and his two sons, or it

might possibly have been a grandfather, father, and son.

"Behold the true kernel of the British

nut!" exclaimed the admiring Matron, as the three men, straight of

limb, flat of back, and broad of shoulder, started off so briskly that

it was impossible to believe they had been bent up nearly double all

day. The boy, whose age was perhaps fourteen, stopped at a gate to

shoulder a heavy bag of potatoes. After he raised the sack over his

shoulder, he stood perfectly erect, in spite of the heavy weight, and,

puckering up his lips, began to whistle what he imagined to be a tune;

then started off at a pace which soon left us far behind.

In Aylsham there is a great old church

of John of Gaunt's time, with a venerable lichgate at the entrance to

the churchyard. The interior, however, has been too much restored, as

is often the case in Norfolk, and it is spoiled by being crowded with

pews.

After the day of delights at Blickling,

we took train the following morning in Norwich, and rattled away,

through corn and turnip-fields, past red farms and square gray church

towers, a brief twenty miles, to Yarmouth on the North Sea shore. The

waves of this sea play wild games, they told us, with parts of the

Norfolk coast. At some points it has wiped out whole villages, at

another it has dashed up great sand-dunes and buried church and tower

and surrounding houses out of sight.

Old Yarmouth, cockney resort though it

be, is more interesting to the lover of the quaint and curious than any

of the other more fashionable and less historic places on the Norfolk

coast. It has, to be sure, a Parade for the pleasure of the tripper,

and long streets of commonplace houses like those of every English

seaside town. Down behind all this modern sea-wall, however, in the

ancient town where the Peggottys wandered, are the curious Yarmouth

Rows. These are narrow passages between the high houses, where

neighbours can shake hands across the opening from the windows of their

homes. Unlike similar passages in old Continental towns, the Yarmouth

Rows are clean and fresh.

We ate our dinner at "The Star," looking

out at the many gaudy boats tied up by the side of the solid stone quay

along the river. Black sails from the Broads, and red sails from the

south coast were drying out side by side, while the sharp-arched

bridge, like a Chinese print, led our eyes over to the weather-worn

warehouses on the other side. Our hot luncheon, price, "two and six,"

was just like any other hot luncheon. It consisted of the usual joint,

potatoes and cabbage, and a tart. With eyes closed, we could imagine

eating it in any part of England through which we had passed, but,

looking over the well-known menu, we forgot its monotony because of the

noble room in which it was served. "The Star" was once the home of one

of those judges who condemned Charles, the king, to death. This room,

with its superbly carved black oak walls, its lovely plaster ceiling

and quaint blue-tiled fireplace, remains as it was in the seventeenth

century, and it is the pride of the present host and owner of the

hotel. Once upon a time a wealthy American offered the generous sum of

six thousand pounds for its panelled walls, ceiling, and fireplace. He

wished to transport them across the ocean to his fine new house in the

States; but the owner of "The Star" proved to be a man of sentiment and

artistic appreciation. He disdained the offer, and we rejoiced in his

admirable decision.

It was on one of our many journeys by

rail through Norfolk that we had caught sight of ruined towers and

arches amid the foliage, and discovered our American weakness for

antiquarian research and the study of church architecture. Therefore,

as we rattled away in the train from Yarmouth, again bound for our

headquarters in Norwich, we agreed upon a bicycle trip or two. Our

conclusion was to follow the queer highways to the haunts of the

ancient, the beautiful, and the gracefully dilapidated. Our

consultation in the railway carriage resulted in an agreement to

forswear a visit to modern and royal Sandringham, and give time and

attention and admiration to Wymondham, where there is a ruined abbey,

and to Thetford, an ancient Royal city.

Wymondham, by the way, is pronounced as

if it were spelled Windham, for Norfolk is the prize county of all

England for serious differences between the spelling and pronunciation

of proper names. In preparation for this bicycle excursion, Polly and I

bestirred ourselves early, and got four wheels down to the ten o'clock

train going south. We had bought tickets both for machines and for the

people who were to ride them, before the Matron and the Invalid came to

the platform gate. The bicycle tickets cost three pence each; without

tickets the wheels are not allowed on the train.

They have a way in rural England of

keeping the railway from spoiling all pretty villages by its bustle and

smoke, and this precaution involves a station sometimes a very long way

from the attractive parts of the little towns. Neither the Invalid nor

the Matron got a chance to fuss nor to make themselves miserable about

the bicycles. We said not a word to them about our arrangements, but

let them enjoy the Norfolk scenery without anxious anticipations. The

substantial walls of Coleman's Mustard Factory, just outside Norwich,

the plumy trees of Hetherset, the ancient granges by the roadside, and

the numerous flint churches so aroused their enthusiasm and engaged

their whole attention that, when we presented them at Wymondham station

with bicycles to ride to the then invisible town, never a question nor

an objection did either of them offer. Their interest and admiration

were wholly absorbed by the long lines of glittering flint walls,

beautifully put together, and surrounding ancient flint churches, with

thatched roofs, built to last to eternity of that proverbially hard

substance. The flints, cracked in half for building, shine in the sun

as though artificially polished, and, at nearer range, show blue,

white, pink, and black, their irregular surfaces shining like jewels.

"I believe the monks have only gone off

for a pilgrimage, and will be back to-morrow," was the Matron's first

comment, as we rode down the street of Wymondham in the shadow of

overhanging gables.

"We shall probably find a fat old

cellarer in here," said Polly, when we entered at the sign of "The

Green Dragon" to order lunch. Never did there exist a more perfect

little hostelry than this. It has lingered on to hale old age from some

time in the thirteenth century, when the abbey was in its glory. Then

this jewel of an inn was used as a shelter for lay guests. It is a cosy

place, but now too small to afford sleeping-room for any but the

innkeeper and his family.

Under the carved beam which supports the

overhanging casements we found an opening to a narrow passage warped by

age or the inaccuracy of the monkish architect. Before this entrance

hangs a nail-studded door strong enough for a fortress. Through a

stuccoed corridor, one way led to the present tap-room. Before the rest

of us had finished admiring the exterior, the Invalid was deep in

conversation with the rosy-cheeked, buxom landlady, who sat behind a

tiny bar. This bar in monkish times was a cupboard. Sticklers for

preservation of antiques as we are, we did not think is a very

aggressive innovation to make a bar of this little bowed window in the

corner, where all the bright mugs and polished glasses hung as a

background to the most respectable of barmaids. The heavy oak beams of

the ceiling in the quaint hall, black with age, are upheld with rudely

carved figures of the knights who may have feasted here. The marks of

the sculptor's tools are upon them and on the carvings which adorn the

great fireplace.

"Don't turn the knob, Polly, or a monk

will pop out of that low cellar door," I advised cautiously, as that

inquisitive maiden embarked on one of her voyages of discovery around

the rooms.

"Tumble out, you mean. I know there is

one in there, all vine grown, who has been sipping for centuries at the

noble wine laid down for guests three hundred years ago," she retorted,

falling in with our mood.

"He can't get out," advised the Matron.

"Don't you see the huge bunch of keys hanging on the antlers above the

door? A prima donna will perhaps trip down those stairs in the corner

if we stop here long enough," she continued, seriously. "Did you ever

lunch in a stage inn before, all set for the first act?"

"I want but one pull at one of those

leather tankards," said Polly, longingly, "and then I shall be able to

tell you more about Wymondham Abbey than any guide-book."

"Yes, ladies, you can have tea and bread

and butter, and eggs any way you choose, ready in half an hour," was

the landlady's practical contribution to the conversation, as, bustling

in, she unconsciously sent our imaginations back to the wants of the

present time.

We stacked our bicycles before the inn's

door, for the churchyard where, among the old cedars, stand the

picturesque remains of the great abbey, is near.

Wymondham Priory was founded in 1107. It

was a very rich institution, with all sorts of privileges, which made

the monks very independent of the higher church authorities. They owned

fields and meadows and all the lands about, and even changed the king's

highway to suit themselves. A quarrel between the prior and a jealous

superior, the Abbot of St. Albans, caused the Pope to turn the priory

into an abbey for the Benedictines in 1448, and such it remained until

the time of the dissolution. Another difference, with the Archdeacon of

Norfolk, took the parish church from the jurisdiction of the abbey, and

it was then that the queer things happened which gave the parish church

its present unusual architectural peculiarities. The Pope decided that

the abbot had no jurisdiction over the parishioners; the monks at once

made a division in the church, and built another tower, in which to

hang the bell which called them to matins and primes. The parish church

with the parish bell-tower is preserved as in ancient times, but the

monks' beautiful tower, built in 1260, is a ruin draped from top to

bottom with green vines. The parish church has a superb wooden ceiling

in the nave, the spandrels springing from the backs of winged angels

resting on grotesque heads.

It is easy to trace the former entrances

to the cloisters, the chapter-house, and the various portions of the

abbey by the closed doorways still visible. Extending over the

churchyard from this fine shattered tower are groups of clustered

columns and picturesque arches, – all that now

remains of the abbey's old glory.

"I am quite satisfied that I have seen

the finest old church in Norfolk," declared the Invalid, our chief

amateur student of antique places of worship. "There may be others,

but, as we have not months to spare here, I am glad to take home a

remembrance of the noble beauty of these dignified aisles."

An ancient font, mutilated but still

beautiful, the pulpit, the chapels, and the base of the font were being

that day decorated with fruits, vegetables, and flowers for the Harvest

Festival.

The many venerable cedars in the

churchyard suit the old place admirably, and so do the solemn, sleepy

dwellings about the close. The old Green Dragon stood genial and

smiling. It will take more storms than the little inn has yet weathered

to wear off the jolly remembrance of its youth.

Whether it was that the landlady heard

Polly's shivering at ghostly monks, or simply because she wanted us to

enjoy freedom from intrusion, but she served our simple lunch in a

little sitting-room, one side all lattice window, and with a ceiling so

low that the shortest member of the party could touch it with an extra

stretch of the arm. Great poppies on the paper and a wide fireplace

caused the Matron to nod approval, as she devoured several extra slices

of delicious cake.

The landlady, probably in gratitude for

being answered all sorts of ingeniously conceived questions about

America, recommended us earnestly to ride out to Stanfield Hall. It is

not more than two miles from town. An atrocious murder having been

committed there in 1808, and Wymondham folk have not yet recovered from

what to them is but a recent excitement. The present house is an

Elizabethan moated grange surrounded by an unkempt park full of

oak-trees; the atmosphere of the place is unaccountably sad and gloomy,

but the melancholy is perhaps not so much due to the tragic death of

the later master who was shot here by his tenant and bailiff, as to the

memories of Amy Robsart, who wandered under the shade of the ancient

trees with Leicester in the short bright days when he wooed her. This

old estate washer father's home. Leicester, then Lord Robert Dudley,

came wounded to old Stanfield Hall when his duty brought him to Norfolk

with the troops at the time of the Ket rebellion, and Amy nursed him

and loved him. The road to Stanfield, one of those perfect Norfolk

highways which puts all other roads to shame, leads along with only one

turn between the town and the Hall, passing fascinating old farmhouses,

none younger than the age of Queen Elizabeth, with their front gardens

decorated with quaint sun-dials, stilted rows of box, and fancifully

trimmed bay-trees.

"We are the perfect time-keepers," said

Polly, as we rode up to the station just one minute before the Thetford

train was due. When we got to Thetford, we very nearly wished we had

stayed in curious old Wymondham.

"This may be an ancient royal city,"

said the Matron, "but it looks more early Victorian."

"But here is one of Mr. Pickwick's inns

to console us," said the Invalid, as we rode into the court of "The

Bell," a marked contrast to the thirteenth-century style of the Green

Dragon.

"Those deceptive guide-books!"

indignantly exclaimed the Matron, without noticing the interruption. "I

supposed these streets would be full of queer old things, and all I see

is a Jane Austen house or two."

We did not ask what a Jane Austen house

was, but we did try to get some information from the green-aproned

Boots at the Bell concerning the King's House, certain assurance of its

existence having been dug by me out of our Norfolk Guide.

"I never heard of no King's House. Did

you mean the house of Mr. King?" was his lucid reply.

The guide-book had told us that

immediately upon entering Thetford we should become conscious of its

antiquity. We stared about in indignant disgust.

"That writer could not have known

Wymondham," said Polly. "I only see Georgian houses, but perhaps we are

not experts."

At last we found the so-called King's

House, a former country residence of English kings, now a plain square

brick mansion set in a garden and showing a small royal emblem stuck up

above the flat cornice.

"This is all the king left there," said

Polly, as she pointed her camera in the air. Thetford, we discovered

for ourselves, possesses an artificial mound as large as the castle

foundations at Norwich. There we also found a fine Elizabethan house

down near the millstream, and outside the town lies a huge

rabbit-warren extending for miles. It seemed to go on for ever over

hill and hollow, and the little cottontails were skipping around, or

sunning themselves outside their front doors, in the tamest sort of

way, not at all like their wild Dartmoor kindred. Their silver-tipped

tails amid the bracken made the whole great undulating plain flash and

sparkle.

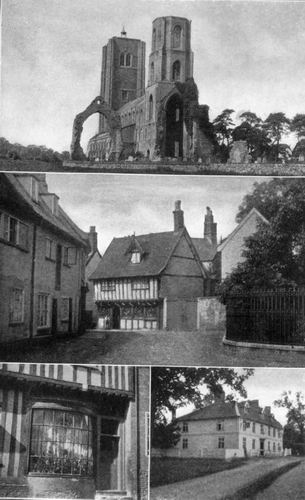

The Ruins of Wymondham Priory. – The Green Dragon

Inn, Wymondham – A Thetford Window

– The Inn At Blickling.

The Bell Inn is the most ancient and

admirable structure remaining in Thetford, but all the quaintness is on

the outside. The inside has followed the prevailing Thetford fashion

and become Georgian. The tea we found was of the extreme modern

sort, – very dear and no flavour.

"After all, it was a delightful day,"

said the Invalid, as we said farewell to the last of the Thetford

antiquities, the abbey gateway near the station, which is really more

royal than the King's House. It led formerly to Thetford Abbey, the

ancient burial-place of the Dukes of Norfolk.

|