| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

The Americanization of Edward Bok Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

IV

A PRESIDENTIAL FRIEND AND A BOSTON PILGRIMAGE EDWARD BOK had not been office boy long before he realized that if he learned shorthand he would stand a better chance for advancement. So he joined the Young Men's Christian Association in Brooklyn, and entered the class in stenography. But as this class met only twice a week, Edward, impatient to learn the art of "pothooks" as quickly as possible, supplemented this instruction by a course given on two other evenings at moderate cost by a Brooklyn business college. As the system taught in both classes was the same, more rapid progress was possible, and the two teachers were constantly surprised that he acquired the art so much more quickly than the other students. Before many weeks Edward could "stenograph" fairly well, and as the typewriter had not then come into its own, he was ready to put his knowledge to practical use. An opportunity offered itself when the city editor of the Brooklyn Eagle asked him to report two speeches at a New England Society dinner. The speakers were to be the President of the United States, General Grant, General Sherman, Mr. Evarts, and General Sheridan. Edward was to report what General Grant and the President said, and was instructed to give the President's speech verbatim. At the dose of the dinner, the reporters came in and Edward was seated directly in front of the President. In those days when a public dinner included several kinds of wine, it was the custom to serve the reporters, with wine, and as the glasses were placed before Edward's plate he realized that he had to make a decision then and there. He had, of course, constantly seen wine on his father's table, as is the European custom, but the boy had never tasted it. He decided he would not begin then, when he needed a clear head. So, in order to get more room for his note-book, he asked the waiter to remove the glasses. It was the first time he had ever attempted to report a public address. General Grant's remarks were few, as usual, and as he spoke slowly, he gave the young reporter no trouble. But alas for his stenographic knowledge, when President Hayes began to speak! Edward worked hard, but the President was too rapid for him; he did not get the speech, and he noticed that the reporters for the other papers fared no better. Nothing daunted, however, after the speechmaking, Edward resolutely sought the President, and as the latter turned to him, he told him his plight, explained it was his first important "assignment," and asked if he could possibly be given a copy of the speech so that he could "beat" the other papers. The President looked at him curiously for a moment, and then said: "Can you wait a few minutes?" Edward assured him that he could. After fifteen minutes or so the President came up to where the boy was waiting, and said abruptly: "Tell me, my boy, why did you have the wine-glasses removed from your place?" Edward was completely taken aback at the question, but he explained his resolution as well as he could. "Did you make that decision this evening?" the President asked. He had. "What is your name?" the President next inquired. He was told. "And you live, where?" Edward told him. "Suppose you write your name and address on this card for me," said the President, reaching for one of the place-cards on the table. The boy did so. "Now, I am stopping with Mr. A. A. Low, on Columbia Heights. Is that in the direction of your home?" It was. "Suppose you go with me, then, in my carriage," said the President, "and I will give you my speech." Edward was not quite sure now whether he was on his head or his feet. As he drove along with the President and his host, the President asked the boy about himself, what he was doing, etc. On arriving at Mr. Low's house, the President went up-stairs, and in a few moments came down with his speech in full, written in his own hand. Edward assured him he would copy it, and return the manuscript in the morning. The President took out his watch. It was then after midnight. Musing a moment, he said: "You say you are an office boy; what time must you be at your office?" "Half past eight, sir." "Well, good night," he said, and then, as if it were a second thought: "By the way, I can get another copy of the speech. Just turn that in as it is, if they can read it." Afterward, Edward found out that, as a matter of fact, it was the President's only copy. Though the boy did not then appreciate this act of consideration, his instinct fortunately led him to copy the speech and leave the original at the President's stopping-place in the morning. And for all his trouble, the young reporter was amply repaid by seeing that The Eagle was the only paper which had a verbatim report of the President's speech. But the day was not yet done! That evening, upon reaching home, what was the boy's astonishment to find the following note: MY DEAR YOUNG FRIEND: — I have been telling Mrs. Hayes this morning of what you told me at the dinner last evening, and she was very much interested. She would like to see you, and joins me in asking if you will call upon us this evening at eight-thirty. Very faithfully yours, RUTHERFORD

B. HAYES.

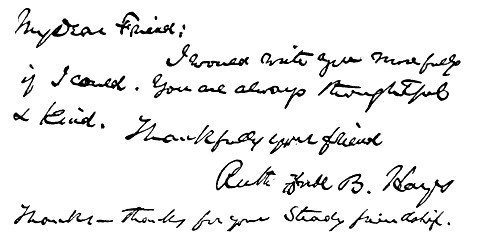

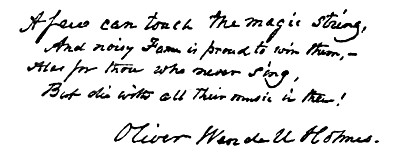

Edward had not risen to the possession of a suit of evening clothes, and distinctly felt its lack for this occasion. But, dressed in the best he had, he set out, at eight o'clock, to call on the President of the United States and his wife! He had no sooner handed his card to the butler than that dignitary, looking at it, announced: "The President and Mrs. Hayes are waiting for you!" The ring of those magic words still sounds in Edward's ears: "The President and Mrs. Hayes are waiting for you!" — and he a boy of sixteen! Edward had not been in the room ten minutes before he was made to feel as thoroughly at ease as if he were sitting in his own home before an open fire with his father and mother. Skilfully the President drew from him the story of his youthful hopes and ambitions, and before the boy knew it he was telling the President and his wife all about his precious Encyclopedia, his evening with General Grant, and his efforts to become something more than an office boy. No boy had ever so gracious a listener before; no mother could have been more tenderly motherly than the woman who sat opposite him and seemed so honestly interested in all that he told. Not for a moment during all those two hours was he allowed to remember that his host and hostess were the President of the United States and the first lady of the land! That evening was the first of many thus spent as the years rolled by; unexpected little courtesies came from the White House, and later from "Spiegel Grove"; a constant and unflagging interest followed each undertaking on which the boy embarked. Opportunities were opened to him; acquaintances were made possible; a letter came almost every month until that last little note, late in 1892:  The simple act of turning down his wine-glasses had won for Edward Bok two gracious friends. The passion for autograph collecting was now leading Edward to read the authors whom he read about. He had become attached to the works of the New England group: Longfellow, Holmes, and, particularly, of Emerson. The philosophy of the Concord sage made a peculiarly strong appeal to the young mind, and a small copy of Emerson's essays was always in Edward's pocket on his long stage or horse-car rides to his office and back. He noticed that these New England authors rarely visited New York, or, if they did, their presence was not heralded by the newspapers among the "distinguished arrivals." He had a great desire personally to meet these writers; and, having saved a little money, he decided to take his week's slimmer vacation in the winter, when he knew he should be more likely to find the people of his quest at home, and to spend his savings on a trip to Boston. He had never been away from home, so this trip was a momentous affair. He arrived in Boston on Sunday evening; and the first thing he did was to despatch a note, by messenger, to Doctor Oliver Wendell Holmes, announcing the important fact that he was there, and what his errand was, and asking whether he might come up and see Doctor Holmes any time the next day. Edward naively told him that he could come as early as Doctor Holmes liked — by breakfast-time, he was assured, as Edward was all alone! Doctor Holmes's amusement at this ingenuous note may be imagined. Within the hour the boy brought back this answer: MY DEAR BOY: I shall certainly look for you to-morrow morning at eight o'clock to have a piece of pie with me. That is real New England, you know. Very

cordially yours, OLIVER

WENDELL HOLMES.

Edward was there at eight o'clock. Strictly speaking, he was there at seven-thirty, and found the author already at his desk in that room overlooking the Charles River, which he learned in after years to know better. "Well," was the cheery greeting, "you couldn't wait until eight for your breakfast, could you? Neither could I when I was a boy. I used to have my breakfast at seven," and then telling the boy all about his boyhood, the cheery poet led him to the dining-room, and for the first time he breakfasted away from home and ate pie — and that with "The Autocrat" at his own breakfast-table! A cosier time no boy could have had. Just the two were there, and the smiling face that looked out over the plates and cups gave the boy courage to tell all that this trip was going to mean to him. "And you have come on just to see us, have you?" chuckled the poet. "Now, tell me, what good do you think you will get out of it?" He was told what the idea was: that every successful man had something to tell a boy, that would be likely to help him, and that Edward wanted to see the men who had written the books that people enjoyed. Doctor Holmes could not conceal his amusement at all this. When breakfast was finished, Doctor Holmes said: "Do you know that I am a full-fledged carpenter? No? Well, I am. Come into my carpenter-shop." And he led the way into a front-basement room where was a complete carpenter's outfit. "You know I am a doctor," he explained, "and this shop is my medicine. I believe that every man must have a hobby that is as different from his regular work as it is possible to be. It is not good for a man to work all the time at one thing. So this is my hobby. This is my change. I like to putter away at these things. Every day I try to come down here for an hour or so. It rests me because it gives my mind a complete change. For, whether you believe it or not," he added with his inimitable chuckle, "to make a poem and to make a chair are two very different things." "Now," he continued, "if you think you can learn something from me, learn that and remember it when you are a man. Don't keep always at your business, whatever it may be. It makes no difference how much you like it. The more you like it, the more dangerous it is. When you grow up you will understand what I mean by an outlet' — a hobby, that is — in your life, and it must be so different from your regular work that it will take your thoughts into an entirely different direction. We doctors call it a safety-valve, and it is. I would much rather," concluded the poet, "you would forget all that I have ever written than that you should forget what I tell you about having a safety-valve." "And now do you know," smilingly said the poet, "about the Charles River here?" as they returned to his study and stood before the large bay window. "I love this river," he said. "Yes, I love it," he repeated; "love it in summer or in winter." And then he was quiet for a minute or so. Edward asked him which of his poems were his favorites. "Well," he said musingly, "I think 'The Chambered Nautilus' is my most finished piece of work, and I suppose it is my favorite. But there are also 'The Voiceless,' 'My Aviary,' written at this window, 'The Battle of Bunker Hill,' and 'Dorothy Q,' written to the portrait of my great-grandmother which you see on the wall there. All these I have a liking for, and when I speak of the poems I like best there are two others that ought to be included — 'The Silent Melody' and 'The Last Leaf.' I think these are among my best." "What is the history of 'The Chambered Nautilus'?" Edward asked. "It has none," came the reply, "it wrote itself. So, too, did 'The One-Hoss Shay.' That was one of those random conceptions that gallop through the brain, and that you catch by the bridle. I caught it and reined it. That is all." Just then a maid brought in a parcel, and as Doctor ' Holmes opened it on his desk he smiled over at the boy and said: "Well, I declare, if you haven't come just at the right time. See those little books? Aren't they wee?" and he handed the boy a set of three little books, six inches by four in size, beautifully bound in half levant. They were his "Autocrat" in one volume, and his better-known poems in two volumes. "This is a little fancy of mine," he said. "My publishers, to please me, have gotten out this tiny wee set. And here," as he counted the little sets, "they have sent me six sets. Are they not exquisite little things?" and he fondled them with loving glee. "Lucky, too, for me that they should happen to come now, for I have been wondering what I could give you as a souvenir of your visit to me, and here it is, sure enough I My publishers must have guessed you were here and my mind at the same time. Now, if you would like it, you shall carry home one of these little sets, and I'll just write a piece from one of my poems and your name on the flyleaf of each volume. You say you like that little verse: "'A few can touch the magic string.' Then I'll write those four lines in this volume." And he did. As each little volume went under the poet's pen Edward said, as his heart swelled in gratitude: "Doctor Holmes, you are a man of the rarest sort to be so good to a boy."  The pen stopped, the poet looked out on the Charles a moment, and then, turning to the boy with a little moisture in his eye, he said: "No, my boy, I am not; but it does an old man's heart good to hear you say it. It means much to those on the down-hill side to be well thought of by the young who are coming up." As he wiped his gold pen, with its swan-quill holder, and laid it down, he said: "That's the pen with which I wrote 'Elsie Venner' and the 'Autocrat' papers. I try to take care of it." "You say you are going from me over to see Longfellow?" he continued, as he reached out once more for the pen. "Well, then, would you mind if I gave you a letter for him? I have something to send him." Sly but kindly old gentleman! The "something" he had to send Longfellow was Edward himself, although the boy did not see through the subterfuge at that time. "And now, if you are going, I'll walk along with you if you don't mind, for I'm going down to Park Street to thank my publishers for these little books, and that lies along your way to the Cambridge car." As the two walked along Beacon Street, Doctor Holmes pointed out the residences where lived people of interest, and when they reached the Public Garden he said: "You must come over in the spring some time, and see the tulips and croci and hyacinths here. They are so beautiful. "Now, here is your car," he said as he hailed a coming horse-car. "Before you go back you must come and see me and tell me all the people you have seen; will you? I should like to hear about them. I may not have more books coming in, but I might have a very good-looking photograph of a very old-looking little man," he said as his eyes twinkled. "Give my love to Longfellow when you see him, and don't forget to give him my letter, you know. It is about a very important matter." And when the boy had ridden a mile or so with his fare in his hand he held it out to the conductor, who grinned and said: "That's all right. Doctor Holmes paid me your fare, and I'm going to keep that nickel if I lose my job for it." |