| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER III. On Propagation and Cultivation in general. _____________________________ 124. IN order to have good Vegetables, Herbs, Fruits, and Flowers, we must be careful and diligent in the Propagation and Cultivation of the several plants; for, though nature does much, she will not do all. He, who trusts to chance for a crop, deserves none, and he generally has what he deserves. 125. The PROPAGATION of plants is the bringing of them forth, or the increasing and multiplying of them. This is effected in several different ways: by seed, by suckers, by offsets, by layers, by cuttings. But, bear in mind, that all plants, from the Radish to the Oak, may be propagated by the means of seed; while there are many plants which can be propagated by no other means; and, of these, the Radish and the Oak are two. Let me just qualify, here, by observing, that I enter not into the deep question (which so many have puzzled their heads with) of equivocal generation. I confine myself to things of which we have a certain knowledge. With regard to Propagation by means other than that of seed, I shall speak of it fully enough under the names of the several plants, which are, as to the way of propagating them, to be considered as exceptions to the general rule. Therefore, I shall, in the present Chapter, treat of propagation by seed only. 126. CULTIVATION must, of course, differ in some respects, to suit itself to certain differences in the plants to be cultivated; but, there are some principles and rules, which apply to the cultivation of all plants; and it is of these only that I propose to speak in the present Chapter. 127. It is quite useless, indeed it is grossly absurd, to prepare land, and to incur trouble and expense, without duly, and even very carefully, attending to the seed that we are going to sow. The sort, the genuineness, the soundness, are all matters to be attended to, if we mean to avoid mortification and loss. Therefore, the first thing is, the _____________________________ SORT OF SEED. 128. We should make sure here; for, what a loss o have late cabbages instead of early ones! As to beans, peas, and many other things, there cannot easily be mistake or deception. But, as to cabbages, cauliflowers, turnips, radishes, lettuces, onions, leeks, and numerous others, the eye is no guide at all. If, therefore, you do not save your own seed, (of the manner of doing which I shall speak by and by,) you ought to be very careful as to whom you purchase of; and, though the seller be a person of perfect probity, he may be deceived himself. If you do not save your own seed, which, as will be seen, cannot always be done with safety, all you can do, is, to take every precaution in your power when you purchase. Be very particular, very full and clear, in the order you give for seed. Know the seedsman well, if possible. Speak to him yourself, on the subject, if you can; and, in short, take every precaution in your power, in order to avoid the mortifications like those of having one sort of cabbage, when you expected another, and ol having rape when you expected turnips or ruta-baga. TRUE SEED. 129. But, besides the kind, there is the genuineness to be considered. For instance, you want sugar-loaf cabbage. The seed you sow may be cabbage: it may, too, be sugar-loaf, or more that than any thing else: but, still, it may not be true to its kind. It may have become degenerate; it may have become mixed, or crossed, in generating. And thus, the plants may very much disappoint you. True seed is a great thing: for, not only the time of the crop coming in, but the quantity and quality of it, greatly depend upon the trueness of the seed. You have plants, to be sure; that is to say, you have something grow; but you will not, if the seed be not true, have the thing you want. 130. To insure truth in seed, you must, if you purchase, take all the precautions recommended as to sort of seed. It will be seen presently, that, to save true seed yourself, is by no means an easy matter. And, therefore, you must sometimes purchase. Find a seedsman that does not deceive you, and stick to him. But, observe, that no seedsman can always be sure. He cannot raise all his seeds himself. He must trust to others. Of course, he may himself, be deceived. Some kinds of seed will keep a good many years; and, therefore, when you find that you have got some very true seed of any sort, get some more of it: get as much as will last you for the number of years that such seed will keep; and, to know how many years the seeds of vegetables and herbs will keep, see paragraph 150. _____________________________ SOUNDNESS OF SEED. 131. Seed may be of the right sort; it may be true to its sort; and, yet, if it be unsound, it will not grow, and, of course, is a great deal worse than useless, because the sowing of it occasions loss of time, loss of cost of seed, loss of use of land, and loss of labour, to say nothing about the disappointment and mortification. Here, again, if you purchase, you must rely on the seedsman; and, therefore, all the aforementioned precautions are necessary as to this point also. In this case (especially if the sowing be extensive) the injury may be very great; and, there is no redress. If a man sell you one sort of seed for another; or, if he sell you untrue seed; the law will give you redress to the full extent of the injury proved; and the proof can be produced. But, if the seed does not come up, what proof have you? You may prove the sowing; but, who is to prove that the seed was not chilled, or scorched in the ground? That it was not eaten by insects there? That it was not destroyed in coming up, or in germinating? 132. There are, however, means of ascertaining, whether seed be sound, or not, before you sow it in the ground. I know of no seed, which, if sound and really good, will not sink in water. The unsoundness of seed arises from several causes. Unripeness, blight, mouldiness, and age, are the most frequent of these causes. The two first, if excessive, prevent the seed from ever having the germinating quality in them. Mouldiness arises from the seed being kept in a damp place, or from its having heated. When dried again it becomes light. Age will cause the germinating quality to evaporate; though, where there is a great proportion of oil in the seed, this quality will remain in it many years, as will be seen in paragraph 150. 133. The way to try seed is this. Put a small quantity of it in luke-warm water, and let the water be four or five inches deep. A mug, or basin, will do, but a large tumbler glass is best; for then you can see the bottom as well as top. Some seeds, such as those of cabbage, radish, and turnip, will, if good, go to the bottom at once. Cucumber, Melon, Lettuce, Endive, and many others, require a few minutes. Parsnip and Carrot, and all the winged seeds, require to be worked by your fingers in a little water, and well wetted, before you put them into the glass; and the carrot should be rubbed, so as to get off part of the hairs, which would otherwise act as the feathers do as to a duck. The seed of Beet and Mangel Wurzel are in a case, or shell. The rough things that we sow are not the seeds, but the cases in which the seeds are contained, each case containing from one to five seeds. Therefore the trial by water is not, as to these two seeds, conclusive though, if the seed be very good; if there be four or five in a case, shell and all will sink in water, after being in the glass an hour. And, as it is a matter of such great importance, that every seed should grow in a case where the plants stand so far apart; as gaps in rows of Beet and Mangel Wurzel are so very injurious, the best way is to reject all seed that will not sink case and all, after being put into warm water and remaining there an hour. 134. But, seeds of all sorts, are, sometimes, if not always, part sound and part unsound; and, as the former is not to be rejected on account of the latter, the proportion of each should be ascertained, if a separation be not made. Count then a hundred seeds, taken promiscuously, and put them into water as before directed. If fifty sink and fifty swim, half your seed is bad and half good; and so, in proportion, as to other numbers of sinkers and swimmers. There may be plants, the sound seeds of which will not sink; but I know of none. If to be found in any instance, they would, I think, be found in those of the Tulip-tree, the Ash, the Birch, and the Parsnip, all of which are furnished with so large a portion of wing. Yet all these, if sound, will sink, if put into warm water, with the wet worked a little into the wings first. 135. There is, however, another way of ascertaining this important fact, the soundness, or unsoundness of seed; and that is, by sowing them. If you have a hot-bed; or, if not, how easy to make one for a hand-glass (see Paragraph 94), put a hundred seeds, taken as before directed, sow them in a flower pot, and plunge the pot in the earth, under the glass, in the hot-bed, or hand-glass. The climate, under the glass, is warm; and a very few days will tell you what proportion of your seed is sound. But, there is this to be said; that, with strong heat under, and with such complete protection above, seeds may come up that would not come up in the open ground. There may be enough of the germinating principle to cause vegetation in a hot-bed, and not enough to cause it in the open air and cold ground. Therefore I incline to the opinion that we should try seeds as our ancestors tried Witches; not by fire, but by water; and that, following up their practice, we should reprobate and destroy all that do not readily sink.

136. This is a most important branch of the Gardener's business. There are rules applicable to particular plants. Those will be given in their proper places. It is my business here to speak of such as are applicable to all plants. 137. First, as to the saving of seed, the truest plants should be selected; that is to say, such as one of the most perfect shape and quality. In the Cabbage we seek small stem, well-formed loaf, few spare, or loose, leaves; in the Turnip, large bulb, small neck, slender-stalked leaves, solid flesh, or pulp; in the Radish, high colour (if red or scarlet,) small neck, few and short leaves, and long top, the marks of perfection are well known, and none but perfect plants should be saved for seed. The case is somewhat different as to plants, which are some male and others female, but, these present exceptions to be noticed under the names of such plants. 138. Of plants, the early coming of which is a circumstance of importance, the very earliest should be chosen for seed; for, they will almost always be found to include the highest degree of perfection in other respects. They should have great pains take with them; the soil and situation should be good; and they should be carefully cultivated, during the time that they are carrying on their seed to perfection. 139. But, effectual means must be taken to prevent a mixing of the sorts, or, to speak in the language of farmers, a crossing of the breeds. There can be no cross between the sheep and the dog; but there can be between the dog and the wolf; and, we daily see it, between the greyhound and the hound; each valuable when true to his kind: and a cross between the two, fit for nothing but the rope; a word which, on this occasion, I use, in preference to that of halter, out of respect for the my dern laws and usages of my native country. 140. There can be no cross between a cabbage and a carrot; but there can be, between a cabbage and a turnip; between a cabbage and a cauliflower nothing is more common; and, as to the different sorts of cabbages, they will produce crosses, presenting twenty, and perhaps a thousand, degrees, from the Early York to the Savoy. Turnips will mix with radishes and ruta-baga; all these with rape; the result will mix with cabbages and cauliflowers; so that, if nothing were done to preserve plants true to their kind, our gardens would soon present us with little besides mere herbage. 141. As to the causes, I pretend not to dive into them. As to the "affectionate feelings" from which the effect arises, I leave that to those who have studied the "loves of the plants." But, as to the effect itself I can speak positively; for, I have now on the table before me an ear of Indian Corn having in it grains of three distinct sorts; WHITE CORN, that is to say, colour of bright rye-straw; YELLOW CORN, that is to say, colour of a deep coloured orange; SWEET CORN, that is to say, colour of drab, and deep-wrinkled, while the other two are plump, and smooth as polished ivory. The plant was from a grain of White Corn; but, there were Yellow, and Sweet, growing in the same field, though neither at less than three hundred yards distant from the white. The whole, or, at least, the greater part, of the White Corn that grew in the patch was mixed (some ears more and some less) in the same way; and each of the three sorts were mixed with the other two, in much about the same proportion that the White Corn was. 142. Here we have the different sorts assembled in the same ear, each grain retaining all its distinctive marks, and all the qualities, too, that distinguish it from the other two. Sometimes, however, the mixture takes place in a different way, and the different colours present themselves in streaks in all the grains of the ear, rendering the colour of the grains variegated instead of their being one-coloured. 143. It is very well known, that effects like this are never perceived, unless in cases where different sorts of Indian Corn grow at no great distance from each other. Probably, too, to produce this intermixture, the plants of the several sorts must be all of the same age; must all be equal in point of time of blowing and kerning. But, be this as it may, the fact of intermixture is certain: and, we have only to know the fact to be induced to take effectual measures to provide against it. 144. As to bees carrying the matter, and impregnating plants with it, the idea appears nonsensical; for, how comes it that whole fields of Indian Corn are thus mixed? And, in the Indian Corn, let it be observed, the ear, that is to say, the grain-stalk, is at about four feet from the ground, while the flower is, perhaps, eight or ten feet from the ground! What, then, is the bee (which visits only the flower) to carry the matter to the flower, and is the flower then to hand it down to the ear? Oh, no! this is much too clumsy and bungling work to be believed in. The effect is, doubtless, produced by scent, or smell; for, observe, the ear is so constructed, and is, at this season, so guarded, so completely enveloped, that it is impossible for any matter whatever to get at the grain, or at the chest of the grain, without the employment of mechanical force. 145. Away, then, I think we may send all the nonsense about the farina of the male flowers being carried to the female flowers, on which so much has been said and written, and in consequence of which erroneous notion gardeners, in dear Old England, have spent so much time in assisting Cucumbers and Melons in their connubial intercourse. To men of plain sense, this is something so inconceivable, that I am afraid to leave the statement unsupported by proof, which, therefore, I shall give in a quotation from an English work on Gardening by the Rev. CHARLES MARSHALL, Vicar of Brixworth in Northamptonshire. "Setting the fruit is the practice of most good gardeners, as generally insuring the embryos from going off, as they are apt to do at an early season; when not much wind can be suffered to enter the bed, and no bees or insects are about, to convey the farina from the male flowers to the female. The male flowers, have been ignorantly called false blossoms, and so have been regularly pulled off (as said) to strengthen the plants; but they are essential to impregnate the female flowers; i. e. those that shew the young fruit at their base: This impregnation, called setting the fruit, is artificially done thus: as soon as any female flowers are fully open, gather a newly opened male flower, and stripping the leaf gently off from the middle, take nicely hold of the bottom, and twirling the top of the male (reversed) over the centre of the female flower, the fine fertilizing dust from the male part will fall off, and adhere to the female part, and fecundate it, causing the fruit to keep its colour, swell, and proceed fast towards perfection. This business of setting the fruit may be practised through the months of February, March, and April, but afterwards it will not be necessary; for the admission of so much air as may afterwards be given, will disperse the farina effectually; but if the weather still is bad, or remarkably calm, setting may be continued a little longer. If short of male flowers, one of them may serve to impregnate two females!" 146. Lest the American reader should be disposed to lament, that such childish work as this is made to occupy the time of English Gardeners, it may not be amiss to inform him, that those to whom the Reverend Gentleman recommends the practising of these mysteries, have plenty of beef and pudding and beer at their masters' expense, while they are engaged in this work of impregnation; and that their own living by no means depends, even in the smallest degree, upon the effect of the application of this "fine fertilizing dust." To say the truth, however, there is nothing of design here, on the part of the gardener. He, in good earnest, believes, that this operation is useful to the growth of the fruit of his cucumber plants: and, how is he to 'believe otherwise, when he sees the fact gravely taken for granted by such men as a Clergyman of the Church of England! 147. Suffice it, now, that we know, that sorts will mix, when seed-plants of the same tribe stand near each other; and we may easily suppose, that this may probably take place though the plants stand at a considerable distance apart, since I have, in the case of my Indian Corn, given proof of mixture, when the plants were three hundred yards from each other. What must be the consequence, then, of saving seed from cucumbers, melons, pumpkins, squashes, and gourds, all growing in the same garden at the same time? To save the seed of two sorts of any tribe, in the same garden, in the same year, ought not to be attempted; and this it is, that makes it difficult for any one man to raise all sorts of seeds good and true. 148. However, some may be saved by every one who has a garden; and, when raised, they ought to be carefully preserved. They are best preserved in the pod, or on the stalks. Seeds of many sorts will be perfectly good to the age of eight or ten years, if kept in the pod or on the stalks, which seeds, if threshed, will be good for little at the end of three years or less. However, to keep seeds, without threshing them out, is seldom convenient, often impracticable, and always exposes them to injury from mice and rats, and from various other enemies, of which, however, the greatest is carelessness. Therefore, the best way is, except for things that are very curious, and that lie in a small compass, to thresh out all seeds. 149. They should stand till perfectly ripe, if possible. They should be cut, or pulled, or gathered, when it is dry; and, they should, if possible, be dry as dry can be, before they are threshed out. If, when threshed, any moisture remain about them, they should be placed in the sun; or, near a fire in a dry room; and, when quite dry, should be put into bags, and hung up against a very dry wall, or dry boards, where they will by no accident get damp. The best place is some room, or place, where there is, occasionally at least, a fire kept in winter. 150.

Thus preserved, kept from open

air and from damp,

the seeds of vegetables

will keep sound and good for sowing for the number years stated in

the following list; to which the reader will particularly attend.

Some of the seeds in this list will keep, sometimes, a year longer,

if very well saved and very well preserved, and especially if closely

kept from exposure to the open air. But, to lose

a crop from unsoundness of

seed is a sad thing, and, it is indeed, negligence wholly inexcusable

to sow seed of the soundness of which we are not certain.

151. Notwithstanding this list, I always sow new seed in preference to old, if, in all other respects, I know the new to be equal to the old. And, as to the notion, that seeds can be the better for being old, even more than a year old, I hold it to be monstrously absurd; and this opinion I give as the result of long experience, most attentive observation, and numerous experiments made for the express purpose of ascertaining the fact. 152. Yet, it is a received opinion, a thing taken for granted, an axiom in horticulture, that Melon seed is the better for being old. Mr. MARSHALL, quoted above, in paragraph 145, says, that it ought to be "about four years old, though some prefer it much older." And he afterwards observes, that "if new seed only can be had, it should be carried a week or two in the breeches-pocket, to dry away some of the more watery particles!" What should we do here, where no breeches are worn! If age be a recommendation in rules as well as in Melon seed, this rule has it; for, English authors published it, and French authors laughed at it, more than a century past! 153. The reader will observe, that, in England, a melon is a melon; that they are not, there, brought into market in wagon loads and boat loads, and tossed down in immense heaps on the stones; but, are carried, by twos, or threes, and with as much care as a new-born baby is carried. In short, they are sold at from a dollar to four dollars apiece. This alters the case. Those who can afford to have melons raised in their gardens, can afford to keep a conjuror to raise them; and a conjuror will hardly condescend to follow common sense in his practice. This would be lowering the profession in the eyes of the vulgar; and, which would be very dangerous, in the eyes of his employer. However, a great deal of this stuff is traditionary; and, as was observed before, how are we to find the conscience to blame a gardener for errors inculcated by gentlemen of erudition! 154. I cannot dismiss this part of my subject without once more cautioning the reader against the danger of unripe seed. In cases where winter overtakes you before your seed be quite ripe, the best way is to pull up the plants and hang them by the heels in a dry, airy place, till all green depart from the stalks, and until they be quite dry, and wholly rid of juice. Even in hot weather, when the seed would drop out, if the plants were left standing, pull, or cut, the plants, and lay them on a cloth in the sun, till the seed be all ready to fall out; for, if forced from the pod, the seed is never so good. Seeds will grow if gathered when they are green as grass, and afterwards dried in the sun; but they do not produce plants like those coming from ripe seed. I tried, some years ago, fifty grains of wheat, gathered green, against fifty, gathered ripe. Not only were the plants of the former feeble, when compared with the latter; not only was the produce of the former two-thirds less than that of the latter; but even the quality of the grain was not half so good. Many of the ears had smut, which was not the case with those that came from the ripened seed, though the land and the cultivation were, in both cases, the same. _____________________________ SOWING. 155. The first thing, relating to sowing, is, the preparation of the ground. It may be more or less fine according to the sort of seed to be sown. Peas and beans do not, of course, require the earth so fine as small seeds do. But, still, the finer the better for every thing; for, it is best if the seed be actually pressed by the earth in every part; and many seeds, if not all, are best situated when the earth is trodden down upon them. 156. Of course the ground should be good, either in itself, or made good by manure of some sort, and, on the subject of manure, see Paragraphs 28 and 29. But, in all cases, the ground should be fresh; that is to say, it should be dug just before the act of sowing, in order that the seeds may have the full benefit of the fermentation, that takes place upon every moving of the earth. 157. Never sow when the ground is wet; nor, indeed, if it can be avoided, perform any other act with, or on, the ground of a garden. If you dig ground in wet weather, you make a sort of mortar of it: it binds when then sun or wind dries it. The fermentation does not take place: and it becomes unfavourable to vegetation, especially if the ground be, in the smallest decree, stiff in its nature. It is even desirable, that wet should not come for some days after ground has been moved; for, if the wet come befo-re the ground be dry at the top, the earth will run together, and will become bound at top. Sow, therefore, if possible, in dry weather, but in freshly-moved ground. 158. The season for sowing will, of course, find a place under the names of the respective plants; and, I do hope, that it is, when I am addressing myself to Americans, unnecessary for me to say, that sowing according to the Moon is wholly absurd and ridiculous, and that it arose solely out of the circumstance, that our forefathers, who could not read, had neither Almanack nor Kalendar, to guide them, and who counted by Moons and Festivals instead of by Months and Days of Month. 159. However, it is necessary to observe, that some, and even many, things, which are usually sown in the Spring, would be better sown in the fall; and, especially when we consider how little time there is for doing all things in the Spring. Parsnips, carrots, beets, onions, and many other things, may be safely sown in the fall. The seed will not perish, if covered by the earth. But, then, care must be taken to sow early enough in the fall for the plants to come up before the frost set in. The seed of all plants will lie safe in this way all the winter, though the frost penetrate to the distance of three feet beneath them, except the seeds of such plants as a slight frost will cut down. The seed of kidney beans, for instance, will rot, if the ground be not warm enough to bring it up. So will the seed of cucumbers, melons, and Indian Corn, unless buried beyond the reach of the influence of the atmosphere, Even early peas would be best sown in the fall, could you have an insurance against mice. We all know, what a bustle there is to get in early peas. If they were sown in the fall, they would start up the moment the frost were out of the ground, and would be ten days earlier in bearing, in spite of every effort made by the spring-sowers to make their peas overtake them. Upon a spot, where I saved peas for seed, last year, some that was left, in a lock of haulm, at the harvesting, and that lay upon the dry ground, till the land was ploughed late in November, came up, in the spring, the moment the frost was out of the ground, and they were in bloom full fifteen days earlier than those, sown in the same field as early as possible in the spring. Doubtless, they would have borne peas fifteen days sooner; but there were but a very few of them, and those standing straggling about; and I was obliged to plough up the ground where they were growing. In some cases it would be a good way, to cover the sown ground with litter, or with leaves of trees, as soon as the frost has fairly set in; but, not before; for, if you do it before, the seed may vegetate, and then may be killed by the frost. One object of this fall-sowing, is, to get the work done ready for spring; for, at that season, you have so many things to do at once! Besides, you cannot sow the instant the frost breaks up; for the ground is wet and clammy, unfit to be dug or touched or trodden upon. So that here are ten days lost. But, the seed, which has lain in the ground all the winter, is ready to start the moment the earth is clear of the winter frost, and it is up by the time you can get other seed into the ground in a good state. Fall-sowing of seeds to come up in the spring is not practised in England, though they there are always desirous to get their things early. The reason is the uncertainty of their winter, which passes, sometimes with hardly any frost at all; and which at other times, is severe enough to freeze the Thames over. It is sometimes mild till February and then severe. Sometimes it begins with severity and ends with mildness. So that, nine times out of ten, their seed would come up and the plants would be destroyed before spring. Besides, they have slugs that come out in mild weather, and eat small plants up in the winter. Other insects and reptiles do the like. From these obstacles the American gardener is free. His winter sets in; and the earth is safely closed up against vegetation till the spring. I am speaking of the North of Virginia, to be sure; but the gardener to the South will adapt the observations to his climate, as far as they relate to it. 160. As to the act of sowing, the distances and depths differ with different plants, and these will, of course, be pointed out under the names of those different plants; but, one thing is common to all seeds; and that is, that they should be sown in rows or drills; for, unless they be sown in this way, all is uncertainty. The distribution of the seed is unequal; the covering is of unequal depth; and, when the plants come up in company with the weeds, the difficulty of ridding the ground of the latter, without destroying the former, is very great indeed, and attended with ten times the labour. Plants, in their earliest state, generally require to be thinned; which cannot be done with regularity, unless they stand in rows; and, as to every future operation, how easy is the labour in the one case and how hard in the other! It is of great advantage to almost all plants to move the ground somewhat deep while they are growing; but, how is this to be done, unless they stand in rows? If they be dispersed promiscuously over the ground, to perform this operation is next to impossible. 161. The great obstacle to the following of a method so obviously advantageous, is, the trouble. To draw lines for peas and beans is not deemed troublesome; but, to do this for radishes, onions, carrots, lettuces, beds of cabbages, and other small seeds, is regarded as tedious. When we consider the saving of trouble afterwards, this trouble is really nothing, even if the drills were drawn one at a time by a line or rule; but, this need not be the case; for, a very cheap and simple tool does the business with as much quickness as sowing at random. 162. Suppose there be a bed of onions to be sown. I make my drills in this way. I have what I call a Driller, which is a rake six feet long in the head. This head is made of White Oak, 2 inches by 2 1/2; and has teeth in it at eight inches asunder, each tooth being about six inches long, and an inch in diameter at the head, and is pointed a little al the end that meets the ground. This gives nine teeth, there being four inches over at each end of the head. In this head, there is a handle fixed of about six feet long. When my ground is prepared, raked nice and smooth, and cleaned from stones and clods, I begin at the left hand end of the bed, and draw across it nine rows at once. I then proceed, taking care to keep the left hand tooth of the Driller in the right hand drill that has just been made; so that now I make but eight new drills, because (for a guide) the left hand tooth goes this time in the drill, which was before made by the right hand tooth. Thus, at every draw, I make eight drills. And, in this way, a pretty long bed is formed into nice, straight drills in a very few minutes. The sowing, after this, is done with truth, and the depth of the covering must be alike for all the seeds. If it be Parsnips or Carrots, which require a wider distance between the rows; or, Cabbage plants, which, as they are to stand only for a while, do not require distances so wide: in these cases, other Drillers may be made. And, what is the expense? There is scarcely an American farmer, who would not make a set of Drillers, for six-inch, eight-inch, and twelve-inch distances, in a winter's day; and, consisting of a White Oak head and handle, and of Locust teeth, every body knows, that the tools might descend from father to son to the fourth or fifth generation. I hope, therefore, that no one will, on the score of tediousness, object to the drilling of seeds in a garden. 163. In the case of large pieces of ground, a hand Driller is not sufficient. Yet, if the land be ploughed, furrows might make the paths, the harrow might smooth the ground, and the hand-driller might be used for onions, or for any thing else. However, what I have done for Kidney Beans is this. I have a roller drawn by an ox, or a horse. The roller is about eight inches in diameter, and ten feet long, To that part of the frame of the roller, which projects, or hangs over beyond the roller behind, I attach, by means of two pieces of wood and two pins, a bar ten feet long. Into this bar I put ten teeth; and near the middle of the bar two handles. The roller being put in motion breaks all the clods that the harrow has left, draws after it the ten teeth, and the ten teeth make ten drills, as deep, or as shallow, as the man chooses who follows the roller, holding the two handles of the bar. The two pieces of wood, which connect the bar with the hinder projecting part of the frame of the roller, work on the pins, so as to let the bar up and down, as occasion may require; and, of course, while the roller is turning, ai the end, the bar, with the teeth in it, is raised from the ground. 164. Thus are ten drills made by an ox, in about five minutes, which would perhaps require a man more than a day to make with a hoe. In short, an ox, or a horse, and a man and a boy, will do twelve acres in a day with ease. And to draw the drills with a hoe would require forty-eight men at the least; for, there is the line to be at work as well as the hoe. Wheat and even Peas are, in the fields, drilled by machines; but beans cannot, and especially kidney beans. Drills must be made; and, where they are cultivated on a large scale, how tedious and expensive must be the operation to make the drills by line and hoe! When the drills are made, the beans are laid in at proper distances, then covered with a light harrow (frame of White-Oak and tines of Locust,) and after all comes the roller, with the teeth lifted up of course; and all is smooth and neat. The expense of such an apparatus is really nothing. The barrel of the roller, and the teeth bar, ought to be of Locust, which never perishes, and the shafts and frame of White-Oak, which, even without paint, will last a lifetime. 165. In order to render the march of the ox straight, my ground was ploughed into lands, one of which took the ten rows of kidney-beans; so that the ox had only to be kept straight along upon the middle of the land. And, in order to have the lands flat, not arched at all, the ground was ploughed twice in this shape, which brought the middle of the lands where the furrows were before. If, however, the ground had been flat-ploughed, without any furrow, there would have been no difficulty. I should have started on a straight side, or on the straightest side, leaving out any crook or angle that there might have been. I should have taken two distant objects, two objects, found, or placed, beyond the end of the work, and should have directed the head of the ox in a line with those two objects. Before I started, I should have measured off the width to find where the ox ought to come to again, and then have fixed two objects to direct his coming back. I should have done this at each end, till the piece had been finished. 166. But, is there no other use, to which this roller could be put? Have I not seen, in the marking of a corn-field, a man (nay, the farmer himself) mounted upon a horse, which dragged a log of wood after it, in order to indicate the lines upon which the corn was to be planted? And have I not, at other times, seen the farmer making these marks, one at a time, with a plough? And have I not seen the beauty of these most beautiful scenes of vegetation marred by the crookedness of the lines thus drawn? Now, take my roller, take all the teeth out but three, let these three be at four feet apart. Begin well on one side of the field; mount your horse: load the teeth well with a stone tied on each; drop the bar; take two objects in your eye; go on, keep the two objects in line, and you draw three lines at once, all straight and parallel, even ii a mile long. Then, turn, and carefully fix the horse again, so that you leave four feet between the outside line drawn before and the inside tooth. You have already measured at the other end (where you started,) and have placed two objects for your guide. Go on, keeping these objects in a line; and you have three more lines. Thus you proceed till the field be finished. Here is a great saving of time; but, were it for nothing but the look, ought not the log to give place to the roller? 167. If I have strayed here out of the garden into the field, let it be recollected, that I write principally for the use of farmers. I now return to garden-sowing. 168. When the seeds are properly, and at suitable distances, placed in the drills, rake the ground, and, in all cases, tread it with your feet, unless it be very moist. Then rake it slightly again; for all seeds grow best when the earth is pressed closely about them. When the plants come up, thin them, keep them clear of weeds, and attend to the directions given under the names of the several plants. _____________________________ TRANSPLANTING. 169. The weather for transplanting, whether of table vegetables, or of trees, is the same as that for sowing. If you do this work in wet weather, or when the ground is wet, the work cannot be well done. It is no matter what the plant is, whether it be a cucumber plant, or an oak-tree. It has been observed, as to seeds, that they like the earth to touch them in every part, and to lie close about them. It is the same with roots. One half of the bad growth that we see in orchards arises from negligence in the planting; from tumbling the earth carelessly in upon the roots. The earth should be fine as possible; for, if it be not, part of the roots will remain untouched by the earth. If ground be wet, it cannot be fine. And, if mixed wet, it will remain in a sort of mortar, and will cling and bind together, and will leave more or less of cracks, when it become dry. 170. If possible, therefore, transplant when the ground is not wet; but, here again, as in the case of sowing, let it be dug, or deeply moved, and well broken, immediately before you transplant into it. There is a fermentation that takes place immediately after moving, and a dew arises, which did not arise before. These greatly exceed, in power of causing the plant to strike, any thing to be obtained by rain on the plants at the time of planting, or by planting in wet earth. Cabbages and Ruta Baga (or Swedish Turnip) I have proved, in innumerable instances, will, if planted in freshly-moved earth, under a burning sun, be a great deal finer than those planted in wet ground, or during rain. The causes are explained in the foregoing paragraph; and, there never was a greater, though most popular error, than that of waiting for a shower in order to set about the work of transplanting. In all the books, that I have read, without a single exception: in the English Gardening books; in the English Farmer's Dictionary, and many other works on English husbandry; in the Encyclopedia; in short, in all the books on husbandry and on gardening that I have ever read, English or French, this transplanting in showery weather is recommended. 171. If you transplant in hot weather, the leaves of the plants will be scorched; but the hearts will live; and the heat, assisting the fermentation, will produce new roots in twenty-four hours, and new leaves in a few days. Then it is that you see fine vegetation come on. If you plant in wet, that wet must be followed by dry; the earth, from being moved in wet, contracts the mortary nature; hardens first, and then cracks; and the plants will stand in a stunted state, till the ground be moved about them in dry weather. If I could have my wish in the planting of a piece of Cabbages, Ruta Baga, Lettuces, or, almost any thing, I would find the ground perfectly dry at top; I would have it dug deeply; plant immediately; and have no rain for three or four days. I would prefer no rain for a month to rain at the time of planting. 172. This is a matter of primary importance. How many crops are lost by the waiting for a shower! And, when the shower comes, the ground is either not dug, or, it has been dug for some time, and the benefit of the fermentation is wholly lost. 173. However, there are some very tender plants; plants so soft and juicy as to be absolutely burnt up and totally destroyed, stems and all, in a hot sun, in a few hours. Cucumbers and Melons, for instance, and some plants of flowers. These which lie in a small compass, must be shaded at least, if not watered, upon their removal; a more particular notice of which will be taken as we proceed in the Lists of the Plants. 174. In the act of transplanting, the main things are to take care not to bury the heart of the plant; and to take care that the earth be well pressed about the point of the root of the plant. To press the earth very closely about the stem of the plant is of little use, if you leave the point of the root loose. I beg that this may be borne in mind; for the growth, and even the life, of the plant, depend on great care as to this particular. See Cabbage, Paragraph 200, for a minute description of the act of planting. 175. As to the propagation by cuttings, slips, layers and offsets, it will be spoken of under the names of the several plants usually propagated in any of those ways. Cuttings are pieces cut off from branches of trees and plants. Slips are branches pulled off and slipped down at a joint. Layers are branches left on the plant or tree, and bent down to the ground, and fastened, with earth laid upon the part between the plant and the top of the branch. Offsets are parts of the root and plant separated from the main root. _____________________________ CULTIVATION. 176. Here, as in the foregoing parts of this Chapter, I propose to speak only of what is of general application, in order to save the room that would be necessary to repeat instructions for cultivation under the names of the several plants. 177. The ground being good, and the sowing, or planting, having been properly performed, the next thing is the after-management, which is usually called the cultivation. 178. If the subject be from seed, the first thing is to see that the plants stand at a proper distance from each other; because, if left too close, they cannot come to good. Let them also be thinned early; for, even while in seed-leaf, they injure each other. Carrots, parsnips, lettuces, every thing ought to be thinned in the seed-leaf. 179. Hoe, or weed, immediately; and, let me observe here, once for all, that weeds never ought to be suffered to get to any size either in field or garden, and especially in the latter. In England, where it rains, or drips, sometimes, for a month together, it is impossible to prevent weeds from growing. But in this fine climate, under this blessed sun, who never absents himself for more than about forty-eight hours at a time, and who will scorch a dock-root, or a dandelion-root, to death in a day, and lengthen a water-melon shoot 24 inches in as many hours: in this climate, scandalous indeed it is to see the garden or the field infested with weeds. 180. But, besides the act of killing weeds, cultivation means moving the earth between the plants while growing. This assists them in their growth: it feeds them: it raises food for their roots to live upon. A mere flat-hoeing does nothing but keep down the weeds. The hoeing when the plants are become stout, should be deep; and, in general, with a hoe that has spanes instead of a mere flat plate In short, a sort of prong in the posture of a hoe And the spanes of this prong-hoe may be longer, or shorter, according to the nature of the crop to be hoed. Deep-hoeing is enough in some cases; but, in others, digging is necessary to produce a fine and full crop. If any body will have a piece of Cabbages, and will dig between the rows of one half of them, twice during their growth, and let the other half of the piece have nothing but a flat-hoeing, that person will find that the half which has been digged between, will, when the crop is ripe, weigh nearly, if not quite, twice as much as the other half. But, why need this be said in an Indian Corn country, where it is so well known, that, without being ploughed between, the corn will produce next to nothing! 181. It may appear, that, to dig thus amongst growing plants is to cut off, or tear off, their roots, of which the ground is full. This is really the case, and this does great good; for the roots, thus cut asunder, shoot again from the plant side, find new food, and send, instantly, fresh vigour to the plant. The effect of this tillage is quite surprizing. We are hardly aware of its power in producing vegetation; and we are still less aware of the distance, to which the roots of plants extend in every direction. 182. MR. TULL, the father of the drill-husbandry, gives the following account of the manner, in which he discovered the distance to which certain roots extend. I should observe here, that he was led to think of the drilling of crops in the fields of England, from having, when in France, observed the effects of inner-tillage on the vines, in the vineyards. If he had visited America instead of France, he would have seen the effects of that tillage, in a still more striking light, on plants, in your Indian Corn fields; for, he would have seen these plants spindling, yellow, actually perishing, to-day, for want of ploughing; and, in four days after a good, deep, clean and careful ploughing, especially in hot weather, he would have seen them wholly change their colour, become of a bright and beautiful green, bending their leaves over the intervals, and growing at the rate of four inches in the twenty-four hours. 183. The passage, to which I have alluded, is of so interesting a nature, and relates to a matter of so much importance, that I shall insert it entire, and also the plates, made use of by MR. TULL to illustrate his meaning. I shall not, as so many others have, take the thoughts, and send them forth as my own; nor, like Mr. JOHN CHRISTIAN CURWEN, steal them from TULL, and give them, with all the honour belonging to them, to a Bishop.

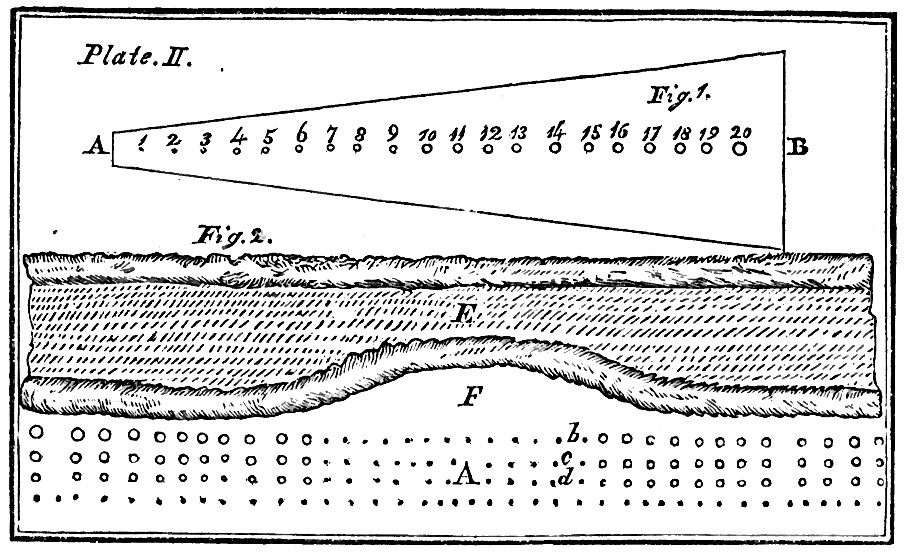

184. "A Method how to find the distance to which roots extend horizontally. A piece, or plot, dug and made fine, in whole hard ground [Plate II. Fig. 1.] the end A. 2 feet, the end B. 12 feet, the length of the piece 20 yards; the figures in the middle of it are 20 Turnips, sown early and well hoed. The manner of this hoeing must be, at first, near the plants, with a spade, and each time afterwards, a foot distance, till the earth be once well dug; and, if weeds appear where it has been so dug, hoe them out shallow with the hand-hoe. But, dig all the piece next the out-lines deep every time, that it may be the finer for the roots to enter, when they are permitted to come thither. If the Turnips be all bigger, as they stand nearer to the end B, it is a proof they all extend to the outside of the piece, and the Turnip 20, will appear to draw nourishment from six foot distance from its centre. But if the Turnips 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, acquire no greater bulk than the Turnip 15, it will be clear, that their roots extend no farther than those of the Turnip 15 does; which is but about 4 foot. By this method the distance of the extent of roots of any plant, may be discovered. There is also another way to find the length of roots, by making a long narrow trench, at the distance you expect they will extend to, and fill it with salt; if the plant be killed by the salt, it is certain that some of the roots enter it. 185. "What put me upon trying this method was an observation of two lands, or ridges (See Plate II. Fig. 2.) drilled with Turnips in rows, a foot asunder, and very even in them; the ground, at both ends and one side, was hard and unploughed. The Turnips not being hoed were very poor, small, and yellow, except the three outside rows, b c d which stood next to the land (or Ridge), E which land, being ploughed and harrowed, at the time the land A ought to have been hoed, gave a dark flourishing colour to these three rows; and the Turnips in the row d, which stood farthest off from the new ploughed land E, received so much benefit from it, as to grow twice as big as any of the more distant rows. The row c being a foot nearer to the new ploughed land, became twice as large as those in d, but the row b, which was next to the land E, grew much larger yet. F is a piece of hard whole ground, of about two perch in length, and about two or three foot broad, lying betwixt those two lands, which had not been ploughed that year; it was remarkable, that during the length of this interjacent hard ground, the rows bed were as small and yellow as any in the land. The Turnips in the row d, about three foot distant from the land E, receiving a double increase, proves they had as much nourishment from the land E as from the land A, wherein they stood, which nourishment was brought by less than half the number of roots of each of these Turnips. In their own land they must have extended a yard all round, else they could not have reached the land, wherein it is probable these few roots went more than another yard, to give each Turnip as much increase as all the roots had done in their own land. Except that it will hereafter appear, that the new nourishment taken at the extremities of the roots in the land, might enable the plants to send out more new roots in their own land, and receive something more from thence. The row c being twice as big as the row d, must be supposed to extend twice as far; and the row b, four times as far, in proportion as it was of a bulk quadruple to the row d." 186. Thus, then, it is clear, that tillage amongst growing plants is a great thing. Not only is it of great benefit to the plants; not only does it greatly augment the amount of the Crop, and make it of the best quality; but, it prepares the ground for another crop. If a summer fallow be good for the land, here is a summer fallow; if the ploughing between Indian Corn prepares the land for wheat, the digging between cabbages and other crops will, of course prepare the land for succeeding crops. 187. Watering plants, though so strongly recommended in English Gardening Books, and so much in practice, is a thing of very doubtful utility in any case, and, in most cases, of positive injury. A country often endures present suffering from long drought; but. even if all the gardens and all the fields could, in such a case, be watered with a watering pot, I much question, whether it would be beneficial even to the crops of the dry season itself. It is not, observe, rain water that you can one time out of a thousand, water with. And, to nourish plants, the water must be prepared in clouds and mists and dews. Observe this. Besides, when rain comes, the earth is prepared for it by that state of the air, which precedes rain, and which makes all things damp, and slackens and loosens the earth, and disposes the roots and leaves for the reception of the rain. To pour water, therefore, upon plants, or upon the ground where they are growing, or where seeds are sown, is never of much use, and is generally mischievous for, the air is dry; the sun comes immediately and bakes the ground, and vegetation is checked, rather than advanced, by the operation. The best protector against frequent drought is frequent digging, or, in the fields, ploughing, and always deep. Hence will arise a fermentation and dews. The ground will have moisture in it, in spite of all drought, which the hard, unmoved ground will not. But always dig or plough in dry weather, and, the drier the weather, the deeper you ought to go, and the finer you ought to break the earth. When plants are covered by lights, or are in a house, or are covered with cloths in the night time, they may need watering, and, in such cases, must have it given them by hand. 188. I shall conclude this Chapter with observing on what I deem a vulgar error, and an error, too, which sometimes produces inconvenience It is believed, and stated, that the ground grows tired, in time, of the same sort of plant; and that, if it be, year after year, cropped with the same sort of plant, the produce will be small, and the quality inferior to what it was at first. Mr. TULL has most satisfactorily proved, both by fact and argument, that this is not true. And I will add this fact, that Mr. MISSING, a Barrister, living in the Parish of Titchfield, in Hampshire, in England, and who was a most excellent and kind neighbour of mine, has a border under a south wall, on which he and his father before him, have grown early peas, every year, for more than forty years; and, if, at any time, they had been finer than they were every one year of the four or five years that I saw them, they must have been something very extraordinary; for, in those years (the last four or five of the more than forty) they were as fine, and as full bearing, as any that I ever saw in England. 189. Before I entirely quitted the subject of Cultivation, there would be a few remarks to be made upon the means of preventing the depredations of vermin, some of which make their attack on the seed, others on the roots, others on the stem, others on the leaves and blossoms, and others on the fruit; but, as I shall have to be very particular on this subject in speaking of fruits, I defer it till I come to the Chapter on Fruits. 190. Having now treated of the Situation, Soil, Fencing, and Laying out of Gardens; on the making and managing of Hot-Beds and Green-Houses; and having given some directions as to Propagation and Cultivation in general; I next proceed to give Alphabetical Lists of the several sorts of plants, and to speak of the proper treatment for each, under the three heads, Vegetables and Herbs, Fruits; and Flowers. |