| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER 27 Arriving

at the shore, Pinocchio quickly looked up and down the coast, but there

was no

dogfish. The sea was as still and as shiny as a looking-glass. "Where

is the dogfish?" he asked, turning to his companions. "It

has gone to breakfast," replied one of them, laughing. "It

may be that, being tired, he has gone to take a little nap," said

another,

laughing still louder. From

these replies Pinocchio understood that the boys had played a trick on

him,

making him believe a thing that was not true. He turned to them and

said

angrily, "And now, why did you tell me this nonsense about the

dogfish?" "Because

we wanted to," they replied in a chorus. "But

why?" "Because

we wanted you to lose a day at school. Aren't you ashamed to go to

school every

day so steadily? And then you are too studious. Why do you do it?" "If

I study, what business is that of yours?" "Why,

it means a great deal to us because it makes us look like bad boys

before the

teacher." "Why?" "Because

the scholars who study are always compared with those who do not; and

we do not

like it. That is all." "And

what should I do in order to make you satisfied with me?" "You

ought to hate school. Both the lessons and the teacher are boys'

greatest

enemies." "And

if I wish to study, what will you do?" "We

will watch for you, and at the first opportunity we will pay you up." "You

make me laugh," said the marionette, shaking his head. "Take

care, Pinocchio!" said the largest boy, going up to him and shaking his

fist under his nose. "Do not make fun of us. Do not be so proud here

because you have no fear of us. We have no fear of you. Remember you

are alone.

We are seven." "Now,

Pinocchio, I will teach you a lesson!" cried another boy. And saying

that,

he struck Pinocchio on the head with his fist. But it was an exchange

of blows,

for the lively marionette ducked his head and replied suddenly with

another

blow, and then the fight became general. Pinocchio, although he was

alone, was

able to defend himself. His hard wooden feet worked so well that they

kept all the

boys at a reasonable distance. Where the feet struck they always left a

black

and blue spot. Then the

boys, provoked at not being able to get near the marionette, looked

around for

stones; but there was nothing but sand. They finally took their

spelling books,

geographies, histories, and arithmetics and began hurling them at him.

But the

marionette was very quick and dodged every one, so that the books went

over him

and fell into the sea. What do

you think the fishes did? Thinking that the books might be something to

eat,

they swam to the edge of the sea and looked at the pictures; but after

swallowing several pages and frontispieces, they spat them out and made

wry

faces, as if to say: "This is no food for us. We are accustomed to eat

much better stuff." Meanwhile the combat grew fiercer until a big old Crab came out of the water and, slowly walking up the beach, cried with the voice of a trombone that has caught a cold, "Stop it! stop it! These battles between boys always end badly. Some misfortune is sure to happen."  Poor

Crab! It was as if he had spoken to the wind. That naughty Pinocchio,

turning

around, said to him very rudely: "Oh, hush, ugly Crab! You would do

better

to eat some seaweed and cure that cold of yours. Go home to bed and

take a good

nap." In the

meantime the boys, who had used up all their own books, looked around

and spied

Pinocchio's, which they seized in less time than it takes to tell it.

Among his

books there was a volume bound in thick cardboard. It was a treatise on

arithmetic. I will leave you to imagine how heavy it must have been.

One of the

boys seized the arithmetic and, taking aim, threw it at Pinocchio.

Instead of

hitting the marionette it struck the head of one of his companions. The

boy

became as white as a sheet and fell to the ground, where he lay

motionless. At the

sight of the little fellow apparently dying the boys were frightened

and ran

away as fast as they could. In a few minutes there was no one left but

Pinocchio. Although

he was more dead than alive through grief and fright, he ran to soak

his

handkerchief in the sea and began to bathe the temples of his poor

schoolmate.

Meanwhile he cried despairingly: "Eugene! My poor Eugene, open your

eyes

and look at me! Why do you not answer me? It was not I who hurt you.

Believe

me, it was not I. If you keep your eyes shut, you will make me die too.

How

shall I be able to go home now? What can I say to my good mamma? What

will she

say to me? Where shall I go? Where can I hide myself? Oh, how much

better, a

thousand times better, would it have been if I had gone to school! Why

did I

listen to them this morning? And to think that the teacher and also my

mamma

warned me, 'Beware of bad companions!' But I am headstrong. I am a bad,

obstinate boy. I let them tell me what to do and then I do what I

please. Why

was I ever made? I have never had a quiet day in my life. Oh, dear!

What will

become of me? What will become of me?" And

Pinocchio continued to cry and weep and pun his head and call poor

Eugene by

name. Suddenly he heard the sound of footsteps. He turned and there

were two

policemen. "What are you doing there?" they asked. "I

am helping my schoolmate." "Is

he hurt?" "It

appears so." "Worse

than that," said one of them, bending down and looking at Eugene

closely;

"the boy is wounded in the temple. Who did it?" "It

was not I," said the marionette, who had hardly any breath left in his

body. "If

you did not do it, who was it then?" "Not

I," repeated Pinocchio. "With

what was he struck?" "With

this book." And the marionette took from the ground the treatise on

arithmetic, bound in thick cardboard, and handed it to the policeman. "Whose

book is this?" "It

is mine." "That

is enough. You must have done it. Stand up and come with us

immediately." ] "But

I — " "Come

with us." "But

I am innocent." "Come with us."  Before

going away the policemen called some fishermen who at that moment were

passing

by in a rowboat near the shore, and said to them: "We trust this

wounded

boy to you. Take him to your house and help him. To-morrow we will come

back

and see how he is." Then

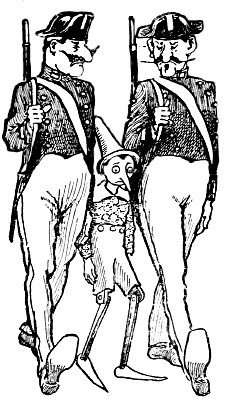

they turned to Pinocchio and, placing him between them, said: "Forward!

Walk quickly! If you do not, so much the worse for you." Without

saying anything the marionette began to walk along the road that led to

his

home. But the poor little boy did not know whether he was in this world

or not.

It appeared to him that he was dreaming, and what a horrible dream it

was! He

was nearly crazy. His eyes saw double. His legs trembled. His tongue

stuck to

the roof of his mouth and he could not say a word. And yet, in the

midst of

that species of stupidity he felt a thorn in his heart at the thought

of

passing under the window of the good Fairy. He would have preferred to

die. They had

already reached the city and were just on the point of entering when a

gust of

wind blew off Pinocchio's hat and carried it along the road back of

them. "Will

you allow me to get my hat?" asked Pinocchio. "Yes,

but do it quickly." The

marionette ran after it, but he did not put it on his head. He placed

it

between his teeth and then began to run toward the sea. He flew like a

musket

ball. The

policemen, judging that they could not catch him, loosened a bloodhound

that

had gained the first premiums at all the dog shows. Pinocchio ran and

the dog

ran after him. All the people, hearing the noise, ran to the front

doors and

windows and wondered who would win the race. But the dog and Pinocchio

made

such a dust as they ran that they were soon hidden and were seen no

more. |