| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

XIII MISHAPS The place where the party had arrived was

very wild

and picturesque. It was on a plateau with perpendicular cliffs rising

on one

side, and a vast chasm on the other. They had come up from below by a

long

winding path. This was somewhat difficult to ascend, and there was

enough of

the semblance of danger in its steepness to make the children feel a

strong

interest in the work of climbing, and to fill their hearts with

satisfaction

and triumph when they reached the elevation to which it conducted them.

Some portions of the plateau were shaded

by tall firs

and pines. Here and there the trunks of ancient trees which had been

overturned

in former years by the winds, lay on the ground concealed by rank

growths of

ferns, laurels, and raspberry bushes. One such, very large, and hollow

at the

big end, lay near where Beechnut had pitched his tent. The open end was

turned

toward the tent, and formed a mouth like that of an oven. From this

open end

the log extended a long distance among the bushes until at last it was

lost in

a mass of stumps and dead tangled branches. When the party left the tent to begin the

gathering

of blueberries, they supposed the spot chosen for their encampment was

so

secluded, that the arrangements they had made there would remain wholly

unseen

and unknown until they returned. They had not, however, been gone more

than

half an hour before the tent was discovered by a strange observer who

was very

much charmed at the sight. This observer was a large and beautiful

mother

squirrel. She was a gray squirrel, and Beechnut had seen her when he

came up

with the tent, standing on a ledge of rock watching anxiously to see

whether he

would go near the place where her nest was. In the nest were her two

little

ones, and she was very anxious lest harm should come to them. After

Beechnut

had put his tent in the cleft he still saw the squirrel standing

motionless on

the rock and watching him. On the following day, as the squirrel was

returning

to her nest with some food for the little ones, she discovered the tent

which

the party had just set up and left. She was astonished and greatly

alarmed. Her

nest was in the hollow tree trunk which has already been described,

about

midway of the length. The squirrel was on the branch of a fir

tree, and she

ran out to the end and stopped to examine the tent more closely. What

could it

be? Was it some sort of a trap set to catch her? Or, was it possible

that it

was an enormous mushroom that had suddenly sprung up out of the ground?

She looked at it very attentively for a

few minutes

without being able to come to any satisfactory conclusion, and then

began to

think of her little ones. She was afraid they were not safe. So she ran

along

the bough of the fir tree to the main stem, and down that to the

ground. Thence

she leaped four feet through the air to her log, ran along on it till

she came

to a small hole in a crotch near the place where her nest was situated

within,

and, lowering her tail, she crept in. To her great joy she found her

young

squirrels perfectly safe. In fact, they were asleep, wholly unconscious

that

any tent had been erected near their dwelling. The squirrel, though much relieved at

finding all

safe at her nest, was by no means easy. She came out of her hole

repeatedly to

look at the tent. Finally she crept softly along toward it, and finding

no

motion or sound was to be observed, she advanced close to it. Finally,

she went

in at the door and crept cautiously around. There were various baskets,

boxes,

and parcels lying on the ground, and she examined these attentively,

smelling

them and attempting to pull them open with her paws. She succeeded in

getting

partly into one parcel which was wrapped in a newspaper, and came to

the edge

of a cracker. She began to nibble. It tasted like corn, she thought,

only much

nicer and more delicate. She was just considering the possibility of carrying home a portion to her young ones when she heard voices and the trampling of feet approaching. Immediately she ran out of the tent, scrambled through the grass to her log, and mounted on the end of it. A boy and two or three girls were coming along the pathway. It was Frank accompanied by some of the younger girls who had got tired of gathering blueberries, and had concluded to come back to the tent and rest there and get ready for dinner.  The squirrel hurried away and got into the

fir tree,

and hiding in the crotch of a limb where she could see without being

seen, she

watched the children to find out what they would do. "Carry your baskets carefully," said

Frank,

"and look where you step, or you will tumble down and spill all your

berries." The girls obeyed this caution and came

forward slowly

until they all reached the tent. "There," said Frank, "we will

set our berries inside, and then we'll get ready for dinner." "What can we do about the dinner?" asked

one of the girls named Augusta. "We can choose a place for it," replied

Frank, "and carry out the things." "Yes, and we can build a fire," said

Augusta. "We shall want a fire." She looked around to find a good spot for

it, and

noticed the log which presented its open end toward where she was

standing.

"There is a grand place," said she, "in the end of that log. The

hollow will do for our fireplace." "But we have no matches," said Frank. "Oh, there are plenty of them in the tent,

somewhere," Augusta responded. "Beechnut always brings matches. I

will hunt for them in the parcels while you are getting some wood." Frank agreed to this proposal, and calling

to

Margaret to come and help him, he began to gather sticks and knots and

dry.

leaves and crowd them into what Augusta called the fireplace. In the

meantime

Augusta was busily employed in the tent, opening baskets and unrolling

parcels

in search of Beechnut's match box. After creating great disorder in her

search

and throwing the things all about the ground inside the tent, she at

last found

the matches and ran to carry them to Frank. While opening the parcels she intended to

tie them up

just as they had been before; but, when she discovered the matches

after such a

long search, she was so excited and overjoyed that she lost all thought

of the

disorder which she had made. The squirrel still remained in the crotch

of the

tree, wondering what these strange intruders into her dominions could

be

intending to do. Frank rubbed a match and lighted the mass

of

combustibles which he had crowded into the hollow log, and he soon had

a

blazing and crackling fire. Augusta ran around in all directions

getting more

fuel. Now and then she broke off small branches from the hemlock trees

growing

in the vicinity and held them in the flames to hear the snapping they

occasioned. The principal portion of the smoke,

ascended in dense

volumes toward the sky. Some of it, however, was forced along inside of

the log

until it reached the dark and narrow niche where the squirrel had made

her

nest. The young squirrels were almost smothered,

and the

mother was in a state of extreme terror and distress. The smoke, the

flames,

the shouts and exclamations of the children, filled her with dismay,

and she

was unable to decide whether to remain where she was to watch the

course of

events, or to hasten back to her hole and endeavor to rescue her little

ones

from the threatened destruction. While things were in this state the

attention of the

children, and the squirrel as well, was arrested by the sudden

appearance of

Beechnut. He came running, out of breath with exertion, and demanded to

know

who had built that fire. Frank was just on the point of boasting of it as his work; but it was plain from Beechnut's air and manner that he considered it an offense to be condemned, and not an exploit to be honored and applauded. So, instead of saying proudly, "I did it," Frank hesitated a moment and then asked, "Why? What is the matter?"  "You must not have a fire here," said

Beechnut. "Come and help me put it out." He began at once to pull away the burning

brands and

scatter them about on the rocks and grass, wherever he saw that there

was

nothing which would be in danger of kindling. "Why must we not have a fire here?"

insisted Frank. "We will talk about that by and by,"

replied Beechnut. "The thing to be done now is to put it out. Go and

get

the ax from the tent. I brought it up yesterday." By the time Frank arrived with the ax,

Beechnut had

pulled the fire entirely to pieces, though the great hollow log was

still

burning, and the flames were working their way farther and farther into

it.

Beechnut took the ax, and going along until he had got beyond the part

which

was on fire he began to cut into the log with heavy and rapid blows. He

was

going to stop the progress of the fire by cutting off the log. As it happened this was the only measure

which could

save the young squirrels in the nest from certain death; though

Beechnut knew

nothing of their presence, and was acting with an entirely different

purpose.

To the mother squirrel the situation seemed worse instead of better.

The hubbub

which Beechnut made in putting out the fire, and the apparent extension

of the

fire itself by the scattering of the brands, and now those terrible

blows of

the ax on her dwelling filled her with double consternation. She

scrambled down

the fir tree, ran along the log, and rushed into her hole, which she

found

filled with suffocating vapor. She curled down over the little

squirrels and

remained for a time stupefied with fright, listening in dismay to the

sound of

the blows Beechnut was dealing all the while on the log at no great

distance

from her nest. Presently the burning end of the log was

cut off and

split to pieces, and the fire reduced to a few smoldering brands.

Beechnut then

started to carry his ax back to the tent. "Now tell me," said Frank, "why I must

not build a fire here." "It was wrong for you to build a fire

here," responded Beechnut, "because you had no permission to build a

fire anywhere. You will have to be punished, I think." Augusta looked a little alarmed, but she

had the

generosity to say that the building of the fire was her fault more than

Frank's, and that if anybody was to be punished she was the one. "No;" said Beechnut, "if a girl and a

boy together do mischief, the boy must bear all the punishment." "Well," said Frank, "what is the

punishment to be?" They were now inside of the tent, and as

Beechnut put

away the ax, he replied, "You must go out there somewhere on the green

grass, and stand on your head and count twenty, ten for you and ten for

Augusta." Frank laughed. "Suppose I cannot stand on

my

head so long," said he. "You must try ten times," was Beechnut's

response, "and if you don't succeed in ten times the ten attempts shall

go

for your punishment." "Very well," said Frank. "Come,

Augusta." Augusta followed him, skipping along very

merrily.

Margaret remained behind and said, looking up anxiously to Beechnut,

"Oh,

dear me! I am afraid he will break his neck." "You need not worry about that," said

Beechnut.

"Who ever heard of a boy breaking his neck by standing on his head?" Soon after this the remainder of the party

returned

to the tent with pails and baskets very heavily laden. After covering

the

berries over with green leaves they set the pails and baskets under the

shade

of some overhanging rocks. Beechnut was busy in the tent getting into

order the

things that Augusta had strewn around, and when he had finished, the

provisions

were all taken to a flat rock which Wallace had selected as a good

place for

the dinner party. At a little distance was a hollow in the

side of a

cliff where Beechnut said Frank and Augusta might build a fire if they

wished. "Here, it will be all right," said he,

"but a fire in that great log might easily have escaped into the woods,

and then have spread and done an immense amount of damage." After the dinner the whole party remained

for some

time sitting on the flat rock enjoying the cool mountain breeze and

talking

together. At length they arose and began to saunter slowly around,

going out to

various points where they could get extended views of the country

below.

Beechnut went to the spring, and worked there arranging some stones

about it in

such a manner as to make it more convenient to get the water. A part of the company, among whom were

Parker,

Wallace, Mary Bell, and Caroline, rambled to the brink of the precipice

which

was near by. Caroline persisted in going quite close to the edge — not

so close

as to be in any danger of falling, yet close enough to make most of the

party

uneasy and uncomfortable. Both Mary Bell and Wallace begged her not to

do so,

but this seemed only to cause her to be more disposed to display her

courage. Parker, however, said there was no reason

for being

timid, and that he believed he could climb down. Mary Bell was afraid

he might

make the attempt and she turned and walked away. The others followed, and they were all

going along

together when Caroline took off her bonnet and began to swing it about

in her

hand, holding it by the strings. "Be careful," said Wallace. "If

the strings should break, or slip through your fingers, your bonnet

would be

carried over the precipice by the wind." "Oh, that would be no matter," responded Caroline. "I dare say Parker would climb down and get it for me, if you were afraid to go."  So she continued to swing her bonnet as

before. The

idea of having a young gentleman engaged in such a difficult and

perhaps

dangerous expedition in her service was a very agreeable one to her

mind, and

without intending to do so she let her fingers relax a little as she

was

thinking of the matter. Before she was aware of it the bonnet had gone

from her

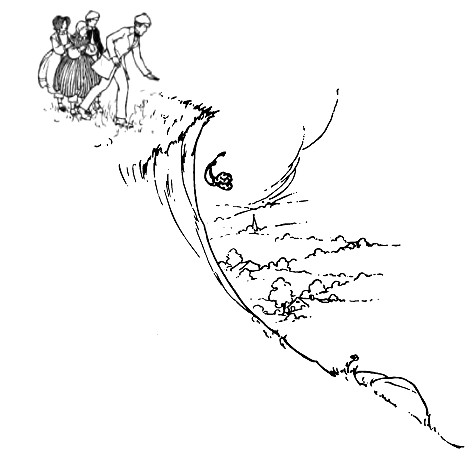

hand and was rolling over and over on the ground. "Stop it!" shouted Parker. Wallace darted forward, but it had reached

the brink

of the precipice and went sailing down through the air until it lodged

on a

projecting shelf of rock a hundred feet below. Caroline looked very

much

alarmed. "What shall I do?" said she. "You can't get it for. me,

can you, Parker?" "Yes," said Parker, "I can get

it." He began to search for a place where it

would be

possible to descend. But he soon returned to his companions with the

report

that the precipice was too steep. Mary Bell and Wallace stood a little aside

from the

others. "Isn't there any way to get down?" asked Mary. "I am not certain," Wallace replied.

"Perhaps I could get down along under the ledges by starting in the

crevice you see a short distance back of where we stand." "I would not try," said Mary. "It is

no matter about the bonnet. She may have mine to wear home, and I will

put a

handkerchief on my head." "I will go and see whether I can get down

or

not," said Wallace. "You need not be anxious about me. I shall not

run any risks. I have no intention of hazarding my life to save a

bonnet." He walked to where he thought the descent

might be

practicable and began to go down. In the meantime the news of the

accident had

spread, and the rest of the children of the party had come running to

join

those who were watching Wallace. They stood on a projecting ledge where

they

could easily see him as he descended. He proceeded cautiously,

sometimes

walking, sometimes going down backward on his hands and knees. At length, to the great relief and joy of

those who

were observing him, he reached the comparatively level spot where the

bonnet

was lying. He took the bonnet up and waved it in the air in token of

the

successful accomplishment of his expedition, and then sat down on the

rock to

rest. A few minutes later he rose and picked a

little

flower that was growing on the verge of the precipice. He put it in the

bonnet

and climbed back up the cliff the way he had come. When he reached the

top he

delivered the bonnet to Caroline, but the flower he gave to Mary Bell. After this the party all came down the

mountain and

went to their several homes. |