| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XIII. A dinner audience

Adventure with a priest Sanatarium for Ningpo missionaries and others

Abies

Kζmpferi Journey to Quanting Bamboo woods and their value

Magnificent

scenery Natives of Poo-in-chee Golden bell at Quan-ting Chinese

traditions Cold of the mountains Journey with Mr. Wang A

disappointment

Adventure with pirates Strange but satisfactory signal

Results.

THE bedroom which I expressed a wish to

occupy, as it

seemed somewhat cleaner than the others, was used during the day by an

itinerant tailor, a native of Fung-hwa-heen, who was in the habit of

going from

place to place to mend or make the garments of his customers. This man

willingly removed to other quarters, and gave the room up tome. He was

a good

specimen of his race, shrewd, intelligent, and formed a striking

contrast to

the priest for whom he was working. Never in all my travels in China

had I met

with such poor specimens of the human race as these same priests. They

had that

vacant stare about them which indicated want of intellect, or at least,

a mind

of a very low order indeed. They did nothing all day long but loll on

chairs or

stools, and gaze upon the ground, or into space, or at the people who

were

working, and then they did not appear to see what was going on, but

kept

looking on and on notwithstanding. The time not spent in this way was

when they

were either eating or sleeping. They were too lazy to carry on the

services of

the temple, which they deputed to a little boy. And thus they spent

their days,

and in this manner they would float down the stream of time until they

reached

the ocean of eternity and were no more seen. There were four or five of these men

connected with

the old monastery, and two or three boys, who were being reared to

succeed

them. . All the men were apparently imbecile, but the superior seemed

to be in

a state approaching to insanity. I seemed to have an extraordinary

attraction

for this man; he never took his eyes off me; wherever I went he

followed at a

certain distance behind, stopping when I stopped, and going on again

when I

went on. When I entered the house he came and peeped in at the window,

and when

I made the slightest motion towards him, he darted off in an instant,

but only

to return again. I began to think his actions extraordinary, and to

feel a

little uneasy about his ultimate intentions. The place and the people

were all

strange to me, and it might so happen that the man was really unsafe.

By day

there was no fear, as I could easily protect myself; but what if he

fell upon

me unawares at night, when I was asleep! I therefore sent for Tung-a,

one of my

servants, and desired him to go out and make some enquiries concerning

the

propensities of the mad priest. Tung-a returned laughing, and told me

there was no

danger; the man was not mad, but that it was partly fear, and partly

curiosity

which made him act in the manner he was doing, and further, that I was

the

first specimen of my race he had seen. During the time I was at dinner, and for

some time

after, in addition to some of the more respectable who were admitted

into the

room, the doors and windows were completely besieged with people. Every

little

hole or crevice had a number of eager eyes peeping through it, each

anxious to

see the foreigner feed. Having finished my dinner and smoked a cigar,

much to

the delight of an admiring audience, I politely intimated that it was

getting

late, that I was tired with the exertions of the day, and that I was

going to

bed. My inside guests rose and retired; but it seemed to me they only

went

outside to join the crowd, and they were determined to see the finale;

they had

seen how I eat, drank, and smoked my cigar, and they now wanted to see

how and

in what manner I went to bed. My temper was unusually sweet at this

time, and

therefore I had no objection to gratify them even in this, providing

they

remained quiet and allowed me to get to sleep. A traveller generally

does not

spend much of his time over the toilet, either in dressing or

undressing, so

that in less time than I would take to describe it I was undressed, the

candle

was put out, and I was in bed. As there was nothing more to be seen the

crowd

left my window, and as they retired I could hear them laughing and

talking

about what they had seen. The chamber in which the head-priest, whom

I have

described, was wont to repose after the fatigues of the day, was behind

the one

occupied by me, and it appeared it was necessary to come through mine

in order

to get into it. I had examined the chamber and learned to whom it

belonged in

the course of the evening. Not caring to be disturbed by having my door

opened

and a person walking through my room after I was in bed and asleep, I

had

suggested to the priest the propriety of going to bed about the same

time as I

did. When the crowd therefore had left my windows, I heard one or two

persons

whispering outside and still lingering there. I called out to them and

desired

them to go away to their beds. "Loya, Loya!"1 a voice

cried, "the Ta-Hosan (high-priest) wants to go to bed."

"Well," said I, "come along, the door is not locked."

"But he has not had his supper yet," another voice replied.

"Tell him to go and get it then, as quickly as possible, for I do not

wish

to be disturbed after I go to sleep." The fatigue of climbing the mountain-pass, and the healthy fresh air of the mountains, soon sent me to sleep, and I dare say the priest might have walked through the room without my knowing anything about it. How long I slept I know not, for the room was quite dark; but I was awakened by the same voices which had addressed me before, and again informed that the Ta-Hosan wanted to come to bed. "Well, well, come to bed and let me have

no more

of your noise," said I, being at the time half-asleep and half-awake;

and

going off sound again immediately I heard no more. Next morning, when I

awoke,

the day was just beginning to dawn, and daylight was streaming through

the

paper window and rendering the tables and chairs in the apartment

partially

visible. The proceedings of the evening seemed to have got mixed up

somehow

with my dreams, but as they became gradually distinct to the mind, and

separated, I began to wonder whether my friend the priest had occupied

his

bedroom during the night. The door was closed and seemed in the same

state in

which I left it when I went to bed, and I could hear no sound of

anything

breathing or moving through the thin partition-wall which divided our

rooms. In

order to satisfy myself I gently opened the door and looked in. But no

priest

was there. The bed had been prepared, and the padded coverlet carefully

folded

for his reception, but all remained in the same condition, and showed

plainly

that no one had occupied the room during the night.

Tung-a now made his appearance with my

morning cup of

tea. It turned out on inquiry that the poor old priest could not get

over his

superstitious dread of me; he was anxious to get to his own bed, and

had

striven hard to accomplish his object; but it was quite beyond his

power. It

was now easy enough to account for his conduct at my window the night

previous.

When it was found he could not conquer his fears a brother priest gave

him a

share of his bed, and I had been left to the undisturbed repose which I

greatly

required. The valley of Tsan-tsin, as I have already

stated, is

high up amongst the mountains, some 1500 or 2000 feet above the level

of the

sea. It is completely surrounded by mountains, many of them apparently

from

3000 to 4000 feet high. Even in the hot summer months, although warm

during the

day in the sun, the evenings, nights, and mornings, are comparatively

cool. At

this time of the year the southwest monsoon is blowing, but ere it

reaches the

valley it passes over a large tract of high mountains, and consequently

gets

cooled on its course. This appears to be the reason why the country,

even at

the foot of the mountains here, is cooler than further down in the

Ningpo

valley. I have frequently thought this would make

an

admirable sanitary station for the numerous missionaries and other

foreigners

who live at Ningpo. Could the Chinese authorities be induced to allow

them to

build a small bungalow or two in the valley, they might thus have a

cool and

healthy retreat to fly to in case of sickness. It is easy of access

even to

invalids, and could be reached in a day and a half, or at most two days

from

Ningpo.

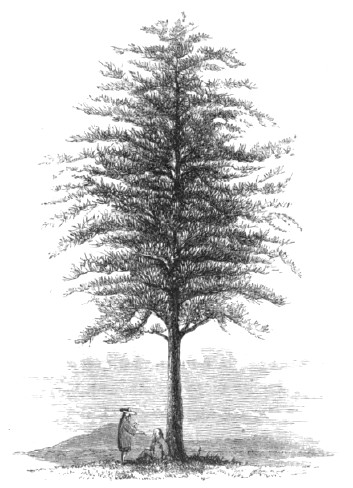

Larch

Tree. I have already noticed a new cedar or

larch-tree

named Abies Kζmpferi discovered amongst these mountains. I had

been

acquainted with this interesting tree for several years in China, but

only in

gardens, and as a pot plant in a dwarfed state. The Chinese, by their

favourite

system of dwarfing, contrive to make it, when only a foot and a half or

two

feet high, have all the characters of an aged cedar of Lebanon. It is

called by

them the Kin-le-sung, or Golden Pine, probably from the rich

yellow

appearance which the ripened leaves and cones assume in the autumn.

Although I

had often made enquiries after it, and endeavoured to get the natives

to bring

me some cones, or to take me to a place where such cones could be

procured, I

met with no success until the previous autumn, when I had passed by the

temple

from another part of the country. Their stems, which I measured, were

fully

five feet in circumference two feet from the ground, and carried this

size,

with a slight diminution, to a height of 50 feet, that being the height

of the

lower branches. The total height I estimated about 120 or 130 feet. The

stems

were perfectly straight throughout, the branches symmetrical, slightly

inclined

to the horizontal form, and having the appearance of something between

the

cedar and larch. The long branchless stems were, no doubt, the result

of their

growing close together and thickly surrounded with other trees, for I

have

since seen a single specimen growing by itself on a mountain side at a

much

higher elevation, whose lower branches almost touched the ground. This

specimen

I shall notice by-and-by. I need scarcely say how pleased I was with

the

discovery I had made, or with what delight, with the permission and

assistance

of the good priests, I procured a large supply of those curious cones

sent to

England in the winter of 1853. I now lost no time in visiting the spot of

my last

year's discovery. The trees were there as beautiful and symmetrical as

ever,

but after straining my eyes for half-an-hour I could not detect a

single cone.

I returned to the temple and mentioned my disappointment to the

priests, and

asked them whether it was possible to procure cones from any other part

of the

country. They told me of various places where there were trees, but

whether

these had seed upon them or not they could not say. They further,

consoled me

with a piece of information, which, although I was most unwilling to

believe

it, I knew to be most likely too true, namely, that this tree rarely

bore cones

two years successively, that last year was its bearing year, and that

this one

it was barren. A respectable looking man, who was on a visit to the

temple, now

came up to me and said that he knew a place where a large number of

trees were

growing, and that if I would visit the temple to which he belonged he

would

take me to this spot, and that there I would probably find what I

wanted. I

immediately took down the name of his residence, which he told me was

Quan-ting, a place about twenty le distant from the temple in

which I

was domiciled, and at a much higher elevation on the mountains. After

making an

appointment for next day he took his leave of me with great politeness,

and

returned to his home. Having procured a guide for Quan-ting, I

set out

early next day to visit my new acquaintance. Leaving the temple of Tsan-tsing, our way

led up a

steep pass, paved with granite stones. On each side of the road were

forests of

fine bamboos the variety called by the Chinese Maou, the

finest I ever

saw. The forests are very valuable, not only on account of the demand

for the

full-grown bamboos, but also for the young shoots, which are dug up and

sold in

the markets in the early part of the season, Here, too, were dense

woods of Cryptotraria, Cunninghamia lanceolata, oaks,

chesnuts, and such like representatives

of a cold or temperate climate. On the road up the mountain pass I met

long trains of

coolies, heavily laden with bamboos, and on their way to the plains.

The weight

of the loads which these men carry is perfectly astonishing; even

little boys

were met carrying loads which I found some difficulty in lifting. All

these

people are accustomed to this work from their earliest years, and this

is no

doubt one of the reasons why they are able to carry such heavy loads. This fine bamboo may be regarded as a

staple

production amongst these mountains, and one of great value to the

natives. In

the spring and early summer months its young shoots furnish a large

supply of

food of a kind much esteemed by the Chinese. At that time of the year

the same

long trains of coolies which I had just met carrying the trees, may

then be

seen loaded with the young shoots. The trees in the autumn and the

young shoots

in spring, are carried down to the nearest navigable stream, where they

are put

on rafts, or in small flat-bottomed boats, and conveyed a few miles

down until

the water becomes deep enough to be navigated by the common boats of

the

country. They are then transferred into the larger boats, and in them

conveyed

to the populous towns and cities in the plain, where they always find a

ready

sale. Thus this valuable tree, which is cultivated at scarcely any

expense,

gives employment and food to the natives of these mountains for nearly

one-half

the year. All the way up the mountain passes the axe of the woodman was

heard

cutting down the trees. In many parts the mountains were steep enough

for the

trees to slide down to the road without any more labour than that

required to

set them in motion. When I reached the top of this pass I got

into a long

narrow valley the valley of Poo-in-chee where the road was nearly

on a

level. This valley must be nearly 1000 feet higher than Tsan-tsing, or

between

two and three thousand feet above the level of the plain. At the top of

the

mountain-pass, and just before entering this valley, some most glorious

views

were obtained. Behind, before, and on my left hand, there was nothing

but steep

and rugged mountains covered with grass and brushwood, but untouched by

the

hand of man, while far down below in a deep dell, a little stream was

dashing

over its rocky bed and hurrying onwards to swell the river in the plain

with

its clear, cool waters. A little further on, when I looked to my right

hand, a

view of another kind, even grander still, met my eye. An opening in the

mountain exposed to view the valley of Ningpo lying far below me, and

stretching away to the eastward for some thirty miles, where it meets

the

ocean, and appeared bounded by the islands in the Chusan Archipelago.

Its

cities, villages, and pagodas were dimly seen in the distance, while

its noble

river was observed winding through the plain and bearing on its surface

hundreds of boats, hurrying to and fro, and carrying on the commerce of

the

country. The picture was grand and sublime, and the impression produced

by it

then must ever remain engraved on my mind. The village of Poo-in-chee is a straggling

little

place and contains but few inhabitants. Many of these mountaineers

indeed,

the greater part of them had never seen a foreigner in their lives.

As I

approached the village the excitement amongst them was very great.

Every living

thing men, women, and children, dogs, and cats seemed to turn out

to look

at me. Many of them, judging from the expression on their countenances,

were

not entirely free from fear. "I might be harmless, but it was just as

possible I might be a cannibal, or somewhat like a tiger." In

circumstances of this kind it is always best to take matters coolly and

quietly. Observing a respectable-looking old man sitting in front of

one of the

best houses in the village, I went up to him and politely asked him if

he

"had eaten his rice." He called out immediately to a boy to bring me

a chair, and begged me to rest a little before I proceeded on my

journey. As

usual, tea was brought and set before me. As I chatted away with the

old man,

the natives gathered confidence and crowded round us in great numbers.

Their

fears soon left them when they found I was much like one of themselves,

although without a tail. Everything about me was examined and

criticised with

the greatest minuteness. My hat, my clothes, my shoes, and particularly

my

watch, were all objects which attracted their attention. I took all

this in good

part, answered all their questions, and I trust when I left them their

opinion

of the character of foreigners had somewhat changed.

Another mountain-pass had now to be got

over, nearly

as high as the last one. When the top of this was gained, I found I was

now on

the summit of the highest range in this part of the country. Our road

now

winded along the tops of the mountains at this elevation for several

miles, and

at last descended into the Quan-ting valley, for which I was bound.

This was

somewhat like the Poo-in-chee valley just described, and apparently

about the

same elevation. Having reached the temple, I had no

difficulty in

finding my acquaintance of the previous day, Mr. Wang-a-nok, as he

called

himself. It now appeared he was a celebrated cook the Soyer of the

district

and had been engaged on this day to prepare a large dinner for a number

of

visitors who had come to worship at the temple. He told me he would be

ready to

accompany me as soon as the dinner was over, and invited me to be

seated in the

priest's room until that time. As there was nothing in the temple of

much

interest, I preferred taking a stroll amongst the hills. Before I set

out I

made inquiry of Wang and the priest whether there were any objects of

interest

in the vicinity more particularly worth my attention. I was told there

was one

place of more than common interest, which I ought to see, and at the

same time

several persons offered to accompany me as guides. We then started off

to

inspect the new wonder, whatever it might turn out to be.

A short distance in the rear of the temple

my guides

halted at the edge of a little pool, which was surrounded with a few

willows

and other stunted bushes. They now pointed to the little pool, and

informed me

this was what they had brought me to see. "Is this all?" said I, with

features which, no doubt, expressed astonishment; "I see nothing here

but

a small pond, with a few water-lilies and other weeds on its surface."

"Oh, but there is a golden bell in that pool," they replied. I

laughed, and asked them if they had seen it, and why they did not

attempt to

get it out. They replied that none of them had seen it, and that it was

impossible to get it out; but that it was there, nevertheless, they

firmly

believed. I confess I was a good deal surprised, and was half inclined

to think

my friends were having a good-humoured joke at my expense, but again,

when I

looked in their faces, I could detect nothing of this kind expressed in

any of

their countenances. Much puzzled with this curiosity, and not

being able

to gain any information calculated to unravel the mystery, I determined

to keep

the subject in mind, and endeavour to get an explanation from some one

who was

better informed than these countrymen appeared to be.

A short time after this I happened to meet

a Chinese

gentleman who had travelled a great deal in many parts of his own

country, and

whose intelligence was of a higher order than that of his countrymen

generally.

To this man I applied for a solution of the Kin-chung, or

golden bell.

When I had described what I bad seen at Quanting, he laughed heartily,

and

informed me that it was simply a superstition or tradition which had

been

handed down from one generation to another, and that the ignorant

believed in

the existence of such things although they did not endeavour to account

for

them. He further informed me such traditions were very common

throughout China,

particularly about Buddhists' temples and other remarkable places

visited by

the natives for devotional purposes. Thus, at the falls in the Snowy

Valley,

which I have already noticed, there was said to be a Heang-loo,

or

incense burner, of fabulous size, which no one had ever seen or were

likely to

see; and a large white horse was said to reside somewhere in the

mountain

called T'hae-bah-san, which rises to the height of 2000 feet behind the

old

monastery of Teintung. All these were simply traditionary stories,

which are

believed by the vulgar and ignorant, but, as my informant said, are

laughed at

by men of education and sound sense. Not being able to find the golden bell,

and as the

sight of the spot where it was supposed to be had not produced the

impression

which my companions and guides had supposed it would, they dropped off,

one by

one, and returned to the temple, while I was left alone to ramble

amongst the

wild scenes of these mountains. There was, however, little time to

spare, and I

was most anxious to secure the services of Mr. Wang the moment he had

finished

his culinary operations. I, therefore, returned to the temple, and

arrived

there soon after the group who had taken me to see the golden bell. I

found

them explaining to the priests and other visitors how disappointed I

had been,

and how incredulous I was as to the existence of the said bell itself. The temple of Quan-ting has no pretensions

as regards

size, and appeared to be in a most dilapidated condition. In one of the

principal halls I observed a table spread and covered with many good

things,

which were intended as an offering to

Buddha. The expected visitors, who appeared to be the farmers and other

respectable inhabitants of the neighbourhood, were arriving in

considerable

numbers, and each one as he came in prostrated himself in front of the

table. As the valley in which the temple is

placed is fully

3000 feet above the sea, I felt the air most piercingly cold, although

it was

only the middle of October, and hot enough in the plains in the

daytime. So

cold was it that at last I was obliged to take refuge in the kitchen,

where Mr.

Wang was busy with his preparations for the dinner, and where several

fires

were burning. This place had no chimney, so the smoke had to find its

way out

through the doors, windows, or broken roof, or, in fact, any way it

could. My

position here was, therefore, far from being an enviable one, although

I got a

little warmth from the fires. I was, therefore, glad when dinner was

announced,

as there was then some prospect of being able to get the services of

Mr. Wang.

The priests and some of the visitors now came and invited me to dine

with them,

and, although I was unwilling, they almost dragged me to the table. In

the

dining-room, which was the same, by-the-bye, in which they were

worshipping on

my arrival, I found four tables placed, at one of which I was to sit

down, and

I was evidently considered the lion of the party. They pressed me to

eat and to

drink, and although I could not comply with their wishes to the fullest

extent,

I did the best I could to merit such kindness and politeness. But I

shall not

attempt a description of a Chinese dinner which, like the dinner

itself, would

be necessarily a long one, and will only say that, like all good

things, it

came to an end at last, and Mr. Wang having finished his in the kitchen

and

taken a supply in his pockets, declared himself ready for my service. Our road led us up to the head of the

valley in which

the temple stands, and then it seemed as if all further passage was

stopped by

high mountain barriers. As we got nearer, however, I observed a path

winding up

round the mountain, and by this road we reached the top of a range of

mountains

fully a thousand feet higher than any we had passed, or 4000 feet above

the

sea. When we reached the top the view that met our eyes on all sides

rewarded

us richly for all the toil of the morning. I had seen nothing so grand

as this

since my journey across the Bohea mountains. On all sides, in whichever

direction I looked, nothing was seen but mountains of various heights

and

forms, reminding one of the waves of a stormy sea. Far below us, in

various directions,

appeared richly cultivated and well wooded valleys; but they seemed so

far off,

and in some places the hills were so precipitous, that it made me giddy

to look

down. On the top where we were there was nothing but stunted brushwood,

but,

here and there, where the slopes were gentle, I observed a thatched hut

and

some spots of cultivation. At this height I met with some lycopods,

gentians,

and other plants not observed at a lower elevation. I also found a

hydrangea in

a leafless state, which may turn out a new species, and which I have

introduced

to Europe. If it proves to be an ornamental species it will probably

prove

quite hardy in England. We had left the highest point of the

mountain ridge,

and were gradually descending, when on rounding a point I observed at a

distance a sloping hill covered with the beautiful object of our search

the Abies

Kζmpferi. Many of the trees were young, and all had apparently been

planted

by man; at least, so far as I could observe, they had nothing of a

natural

forest character about them. One tree in particular seemed the queen of

the

forest, from its great size and beauty, and to that we bent our steps.

It was

standing all alone, measured 8 feet in circumference, was fully 130

feet high,

and its lower branches were nearly touching the ground. The lower

branches had

assumed a flat and horizontal form, and came out almost at right angles

with

the stem, but the upper part of the tree was of a conical shape,

resembling

more a larch than a cedar of Lebanon. But there were no cones even on

this or

on any of the others, although the natives informed us they had been

loaded

with them on the previous year. I had, therefore, to content myself

with

digging up a few self-sown young plants which grew near it; these were

afterwards

planted in Ward's cases and sent to England, where they arrived in good

condition. I now parted from my friend Mr. Wang, who

returned to

his mountain home at Quan-ting, while I and my guide pursued our

journey

towards the temple at which I was staying by a different route from

that by

which we had come. The road led us through the same kind of scenery

which I

have endeavoured to describe mountains; nothing but mountains, deep

valleys,

and granite and clay-slate rocks now bleak and barren, and now richly

covered

with forests chiefly consisting of oaks and pines. We arrived at the

monastery

just as it was getting dark. My friends, the priests, were waiting at

the

entrance, and anxiously inquired what success had attended us during

the day. I

told them the trees at Quanting were just like their own destitute of

cones.

"Ah!" said they, for my consolation, "next year there will be

plenty." I cannot agree with Dr Lindley in calling

this an Abies,

unless cedars and larches are also referred to the same genus. It is

apparently

a plant exactly intermediate between the cedar and larch; that is, it

has

deciduous scales like the cedar and deciduous leaves like the larch,

and a

habit somewhat of the one and somewhat of the other. However, it is a

noble

tree; it produces excellent timber, will be very ornamental in park

scenery,

and I have no doubt will prove perfectly hardy in England.

I had been more successful in procuring

supplies of

tea and other seeds and plants for the Himalayas than I had been in my

search

for the seeds of the new tree just noticed. Large supplies had been got

together at Ningpo at various times during the summer and autumn, and

these

were now ready to be packed and shipped for India. For this purpose it

was

necessary to proceed to Shanghae; but to get there in safety was no

easy matter

at this time, owing to the numerous bands of pirates which were then

infesting

the coasts. The Chinese navy either would not, or perhaps it would be

more

correct to say they durst not, make the attempt to put them down.

Hence, while

these lawless gentry were ravaging the coast, the brave Chinese

admirals and

captains were lying quietly at anchor in the rivers and other safe

places where

the pirates did not care to show themselves. In going up and down this dangerous coast

I was

greatly indebted to Mr. Percival, the managing partner of Messrs.

Jardine

Matheson and Co.'s house at Shanghae, and to Mr. Patridge, who had the

charge

of the business of that house at Ningpo. By their kindness I was always

at liberty

to take a passage in the "Erin," a boat kept constantly running up

and down in order to keep up the communication between the two ports.

This boat

was well manned and armed, and, moreover, she was the fastest which

sailed out

of Ningpo. The Chinese pirates knew her well: they

also knew that her crew would fight, and that they had the means to

do so, and although she often carried a cargo of great value, I never

knew of

her being really attacked, although she was frequently threatened. On this occasion, as usual, I availed

myself of Mr.

Patridge's kindness, and had all my collections put on board of the

"Erin." My fellow-passengers were the Rev. John Hobson, the Shanghae

chaplain, and family, and the Rev. Mr. Burdon, of the Church Missionary

Society,

who had also secured passages in the "Erin" in order to escape

falling into the hands of the pirates. Leaving Ningpo at daybreak, with the

ebb-tide and a

fair wind, we sailed rapidly down the river, and in three hours we were

off the

fort of Chinhae, where the river falls into the sea. As we passed

Chinhae

anchorage a number of boats got up their anchors and stood out to sea

along

with us, probably with the view of protecting each other, and getting

that

protection from the "Erin" which her presence afforded. When we had

got well out of the river, and opened up the northern passage, a sight

was

presented to view which was well calculated to excite alarm for our

safety.

Several piratical lorchas and junks were blockading the passage between

the

mainland and Silver Island, and seizing every vessel that attempted to

pass in

or out of the river. These vessels were armed to the teeth, and manned

with as

great a set of rascals as could be found on the coast of China. These lawless hordes went to work in the

following

manner. They concealed themselves behind the islands or headlands until

the

unfortunate junk or boat they determined to pounce upon had got almost

abreast

of them, and too far to put about and get out of their way. They then

stood

boldly out and fired into her in order to bring her to; at the same

time

hooting and yelling like demons as they are. The unfortunate vessel

sees her

position when too late; in the most of instances resistance is not

attempted,

and she becomes an easy prize. If resistance has not been made, and no

lives

lost to the pirate, the captain and crew of the captured vessel are

treated

kindly, although they are generally plundered of everything in their

possession

to which the pirates take a fancy. The jan-dows, as the pirates are

called, have

their dens in out-of-the-way anchorages amongst the islands, and to

these

places they take their unfortunate prizes, either to be plundered or to

be

ransomed for large sums by their owners at Ningpo, according to

circumstances.

Negotiations are immediately commenced; messengers pass to and fro

between the

outlaws at the piratical stations, only a few miles from the mouth of

the

river, and the rich ship-owners at Ningpo; and these negotiations are

sometimes

carried on for weeks ere a satisfactory arrangement can be made between

the

parties concerned. And it will scarcely be credited but it is true

nevertheless that within a few miles from where these pirates with

their

prizes are at anchor there are numerous Chinese "men-of-war"(!) manned

and armed for the service of their country. Many of the boats which had weighed anchor

as we

passed Chinghae put about and went back to their anchorage. The little

"Erin," however, with several others, stood boldly onwards in the

direction of the piratical fleet, and were soon in the midst of it. At

this

time some of them were engaged in capturing a Shantung junk which had

fallen

into the trap they had laid for her. We were so near some of the others

that I

could distinctly see the features of the men, and what they were doing

on the

decks of their vessels. They seemed to be watching us very narrowly,

and in one

vessel the crew were getting their guns to bear upon our boat. They

were

perfectly quiet, however; no hooting or yelling was heard, and as these

are the

usual preludes to an attack it was just possible they were prepared to

act on

the defensive only. The whole scene was in the highest degree

exciting;

their guns were manned, the torch was ready to be applied to the

touchhole, and

any moment we might be saluted with a cannon-ball or a shower of grape.

Our

gallant little boat, however, kept on her way, nor deviated in the

slightest

degree from her proper course. The steersman stood fast to the helm,

the master

Andrew, a brave Swede walked on the top of the house which was

built over

three-parts of the deck, and the

passengers crowded the deck in front of the house. Every eye was fixed

upon the

motions of the pirates. When our excitement was at the highest

pitch the

pirates hoisted a signal, which was a welcome sight to our crew, and

although I

have, perhaps, as much bravery as the generality of people, I confess

it was a

welcome sight to myself. The signal which produced such results was

neither

more nor less than a Chinaman's jacket hoisted in the rigging. I

believe any

other article of clothing would do equally well. It will not be found

in

Marryat's code, but its meaning is, "Let us alone and we will let

you." This amicable arrangement was readily agreed to; a jacket was

hoisted in our rigging as a friendly reply to the pirates, and we

passed

through their lines unharmed. During the time they were in sight we

observed

several vessels from the north fall into their hands. They were in such

numbers, and their plans were so well laid, that nothing that passed in

daylight could possibly escape. Long after we had lost sight of their

vessels

we saw and pitied the unsuspecting northern junks running down with a

fair wind

and all sail into the trap which had been prepared for them. We experienced head-winds nearly the whole

way, and,

consequently, made a long passage, and had frequently to anchor. I

rather think

Andrew attributed this luck to the two clergymen we had on board; but

if he did

he may be excused, for wiser heads than his have had their prejudices

on this

point. Whatever luck we had as regards the weather we were certainly

most

fortunate in getting so well out of the hands of the pirates, and in

fairness

this ought to be taken into consideration. 1 Mode

of addressing mandarins and high government officers a term of

respect. |