| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER V. Visit a collector of ancient

works of art His house and

garden Inspect his collections of old crackle china and other vases,

&c.

Fondness of Chinese for their own ancient works of art Description

of

ancient porcelain most prized by them Ancient enamels Foo-chow

enamels

Jade-stone Rock crystal Magnetic iron and other minerals

Gold-stone Red

lacquer and gold japan Porcelain bottles found in Egyptian tombs

Found also

in China at the present day Age of these Mr. Medhurst's

remarks.

A SHORT time after the events took place

which I have

related in the last chapter, and before leaving this part of the

country, I

paid a visit to another Chinese gentleman, whose acquaintance I had

formerly

made in an old curiosity shop in Ningpo. Like myself he was an ardent

admirer

and collector of ancient works of art, such as specimens of china,

bronzes,

enamels, and articles of that description. Neither of us collected what

are

commonly known as curios, such as ivory balls, grotesque and ugly

carvings in

bamboo or sandalwood or soapstone, and such things as take the fancy of

captains of ships and their crews of jolly tars when they visit the

Celestial Empire.

Above all things, our greatest horror was modern chinaware, an article

which

proves more than anything else in the country how much China has

degenerated in

the arts. The venders of such things as

we were in the habit of collecting knew us both well, and not

frequently made

us pay for the similarity of our tastes. Oftentimes I was informed, on

asking

the price of an article, that my Tse-kee friend was anxious to get it,

and had

offered such and such a price, and I have no doubt the same game was

played

with him. That what they told me was sometimes true I have no doubt,

for in

more than one instance I have known specimens purchased by him the

moment he

heard of my arrival. But for all this rivalry we were excellent

friends, and he

frequently invited me to visit him and see his collections when I came

to

Tse-kee.

Curious

Pilgrim-shaped bottle,

enameled with butterflies & etc. I found him the owner and occupant of a

large house

in the centre of the city, and apparently a man of considerable wealth.

He

received me with the greatest cordiality, and led me in the usual way

to the

seat of honour at the end of the reception-hall. His house was

furnished and

ornamented with great taste. In front of the room in which I had been

received

was a little garden containing a number of choice plants in pots, such

as

azaleas, camellias, and dwarfed trees of various kinds. The ground was

paved

with sandstone and granite, and, while some of the pots were placed on

the

floor, others were standing on stone tables. Small borders fenced with

the same

kinds of stone were filled with soil, in which were growing creepers of

various

kinds which covered the walls. Here were the favoured Glycine

sinensis,

roses, jasmines, &c., which not only scrambled over the walls, but

were led

inward and formed arbours to afford shade from the rays of the noonday

sun. In

front of these were such things as Moutans, Nandina (sacred bamboo of

the

Chinese), Weigela rosea, Forsythia viridissima, and Spiræa

Reevesiana.

In opposite corners stood two noble trees of Olea fragrans, the

celebrated

"Kwei-hwa," whose flowers are often used in scenting tea; while many

parts of the little border were carpeted with the pretty little Lycopodium

cæsium, which I introduced to England some years ago. This pretty

fairy-like

scene was exposed to our view as we sat sipping our tea, and with all

my

English prejudice I could not but acknowledge that it was exceedingly

enjoyable. The reception-room was hung with numerous

square

glass lanterns gaily painted with "flowers of all hues;" several

massive varnished tables stood in its centre, while a row of chairs was

arranged down each side. Between the chairs stood small square tables

or

tepoys, on some of which were placed beautiful specimens of ancient

china

vases. Everything which met the eye told in language not to be mistaken

that

its owner was not only a man of wealth, but of the most refined taste. After a few commonplace civilities passing

between us

I expressed a wish to inspect his collections. He led me from room to

room and

pointed out a collection which was enough to make one's "mouth

water." In some instances his specimens stood on tables or on the

floor,

while in others they were tastefully arranged in cabinets made

expressly for

the purpose of holding them. He showed me many exquisite bits, of

crackle of

various colours grey, red, turquoise, cream, pale yellow, and indeed

of

almost every shade. One vase I admired much was about two feet high, of

a deep

blue colour, and covered with figures and ornaments in gold; another of

the

same height had a while ground with figures and trees in black, yellow,

and

green rare and bright colours lost now to Chinese art, and never

known in any

other part of the world.

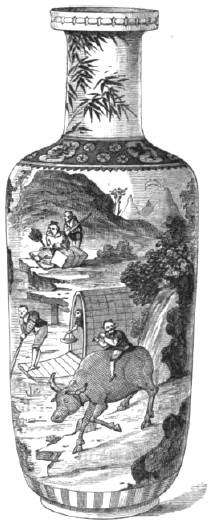

Porcelain

vase enamelled with

figures of Animals & Plants In one of the

rooms I observed some handsome

specimens of red lacquer most elaborately and deeply carved, and also

fine

pieces of gold japan. There were also numerous bronzes and enamels on

copper,

which my friend informed me were from 800 to 1000 years of age. His

collections

of jades and agates was also extensive and valuable.

Taking the collection as a whole, it was

the finest I

had ever seen, and was a real treat to me. On going round the different

rooms I

observed more than one specimen I had been in treaty for myself, and I

thought

I could detect a good-humoured smile upon my friend's countenance, as

the same

idea was passing through his mind which was passing through my own. On returning to the reception-room I found

one of the

tables covered with all sorts of good things for luncheon, which I was

now

asked to partake of. It was, however, getting late in the afternoon,

and near

my own dinner-hour, so I begged myself off with the best grace

possible, and

with many low bows and thanks took my leave much gratified with what I

had

seen. It is well known that the Chinese value

ancient works

of art, but they differ from western nations in this, that the

appreciation of

such articles is confined to those of their own country. As a general

rule they

do not appreciate articles of foreign art, unless such articles are

useful in

daily life. A fine picture, a bronze, or even a porcelain vase of "barbarian"

origin, might be accepted as a present, but would rarely be bought by a

Chinese

collector. But while they are indifferent about the

ancient

works of art of foreign countries, they are passionately fond of their

own. And

well they may, for not only are many of their ancient vases exquisite

specimens

of art, but they are also samples of an art which appears to have long

since

passed from amongst them. Take, for example, their modern porcelain,

examples

of which may be seen in almost every tea-shop in London. The grotesque

figuring

is there it is true, but nowhere do we find that marvellous colouring

which is

observed on their ancient vases. I often tried to find out whether as a

nation

they had lost the art of fixing the most beautiful colours, or whether

in these

days of cheapness they would not go to the expense. All my inquiries

tended to

show that the art had been lost, and indeed it must be so, otherwise

the high

prices which these beautiful things command would be sure, in a country

like

China, to produce them. Without coloured drawings it is difficult

to give the

general reader a correct idea of what these specimens are which are so

much

prized by the Chinese; and although there are some valuable private

collections

in England, yet our museums, to which the public have access, are but

meagrely

supplied. My descriptions, however, will probably be understood by

collectors

of such articles in this country.

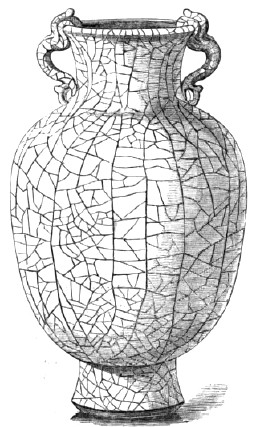

Vase

of Sea-green Crackle. To begin with what is called old crackle

porcelain by

collectors. The Chinese have many kinds of this manufacture, some of

which

are extremely rare and beautiful. In the whites and greys the crackle

is

larger, and the older specimens are often bound by a metallic-looking

band,

which sets off the specimens to great

advantage. White and grey are the common colours amongst modern crackle

a

manufacture not appreciated either by the Chinese or ourselves but

the latter

is easily known from its inferiority to the more ancient. The yellow

and

cream-coloured specimens are rare and much prized these are seldom seen

in

Europe. The greens, light and dark, turquoise, and reds are generally

finely

glazed, and have the crackle-lines small and minute. In colouring these

examples are exquisite, and in this respect they throw our finest

specimens of

European porcelain quite into the shade. The green and turquoise

crackle made in

China at the present day are very inferior to the old kinds. Perhaps

the rarest

and most expensive of all ancient crackles is a yellowish stone-colour;

in my

researches I have seen only one small vase of this kind, and it is now

in my

collection.

Of other ancient porcelain (not crackle)

prized by

the Chinese, I may mention the specimens (generally vases) with a white

ground,

enamelled with figures of various colours, as green, black, and yellow.

It is a

curious fact that the attempts made at the present day by porcelain

manufacturers to fix such colours invariably fail.

The self-coloured specimens, such as pure

whites,

creams, crimsons, reds, blues, greens, and violets, are very fine, and

much

prized by Chinese collectors. Some exquisite bits of colouring amongst

this

class may be met with sometimes in their cabinets, and also in old

curiosity

shops. I purchased a vase in Canton about fourteen inches high,

coloured with

the richest red I had ever seen. I doubt much if all the art of Europe

could

produce such a specimen in the present day, and, strange though it may

appear,

it could certainly not be produced in China. But the most ancient examples of

porcelain, according

to the testimony of Chinese collectors, are in the form of circular

dishes with

upright sides, very thick, strong, and heavy, and invariably have the

marks of

one, two, or three, on the bottom, written in this form, II, III. The

colours

of some of these rare specimens, which have come under my observation,

vary;

but the kinds most highly prized have a brownish-yellow ground, over

which is

thrown a light shot sky-blue, with here and there a dash of blood-red.

The

Chinese tell us there are but a few of these specimens in the country,

and that

they are more than a thousand years old. A specimen shown me by a

Chinese

merchant in Canton was valued at three hundred dollars! In endeavouring

to make

a dealer lower his price for one in Shanghae, he quietly put it away,

telling

me at the same time that I evidently did not understand the value of

the

article I wished to purchase. It was with some difficulty I got him to

produce

it again, and eventually I procured it for a much less sum than I could

have

done in Canton.

Ancient

Porcelain Vessel. Within the last few years the attention of

collectors

in this country has been drawn to the ancient enamels of China. Many

fine

specimens were seen in the Great Exhibition of the Works of Art of all

Nations

in Hyde Park, and since that time a number of specimens have found

their way

into Europe. The specimens to which I allude have the enamel on copper,

beautifully coloured and enlivened with figures of flowers, birds, and

other

animals. The colouring is certainly most chaste and effective, and well

worth

the attention of artists in this country. According to the testimony of

the

Chinese, this manufacture is of a very early period; no good specimens

have

been made for the last six or eight hundred years.

Ancient

Vase enamelled on Metal. In the province of Fokien I met with some

ancient

bronzes, beautifully inlaid with white metal or silver. These were

rarely seen

in any other part of China. The lines of metal are small and delicate,

and are

made to represent flowers, trees, animals of various kinds, and

sometimes

Chinese characters. Some fine bronzes, inlaid with gold, are met with

in this

province. As a general rule, Chinese bronzes are more remarkable for

their

peculiar, and certainly not very handsome, form than for anything else.

There

are, however, many exceptions to this rule. The curiosity-shops, which are met with in

all rich

cities, as well as the cabinets of collectors, are generally rich in

fine

specimens of the jade-stone cut into many different forms. The clear

white and

green specimens are most prized by collectors. Considering the hardness of this stone, it

is quite

surprising how it is cut and carved by Chinese workmen, whose tools are

generally of the rudest description. Fine specimens of rock-crystal,

carved

into figures, cups, and vases, are met with in the curiosity-shops of

Foo-chow-foo. Some of these specimens are white, others golden-yellow,

and

others again blue and black. One kind looks as if human hair was thrown

in and

crystallized. Imitations of this stone are common in Canton made into

snuff-bottles, such as are commonly used by the Chinese.

Amongst other stones and minerals which

are found

amongst the Chinese are lapis-lazuli, malachites, magnetic iron, and

numerous

other samples of the rarer productions of the country. But the most

curious and

most expensive of all is what is called gold-stone. This is an article

of great

beauty, and very different from the imitation kinds which are made in

France,

and largely exported to India. Samples of the imitation frequently find

their

way to Canton, but are little valued by the natives. Most of the

Chinese,

learned in such matters, with whom I came in contact, affirmed the true

gold-stone to be a natural production, and said it came from the

islands of

Japan. It is very rare in China; I have not met with it in India; and

whether

it be a natural production or a work of art, it is certainly extremely

beautiful. My friend Mr. Beale, of Shanghae, who has some fine

specimens,

presented one to me for the purpose of having it examined in London,

but I have

not yet had time. Specimens of red lacquer, deeply carved

with figures

of birds, flowers, &c., and generally made in the form of trays,

boxes, and

sometimes vases, are met with in the more northern Chinese towns, and

are much

and justly prized. What is called "old gold japan" lacquer is also

esteemed by Chinese connoisseurs, and the specimens of this are

comparatively

rare in the country at the present day. These are a few of the principal ancient

works of art

met with in the cabinets of the Chinese and in the old curiosity-shops

which we

find in all large towns. According to the united testimony of my

Chinese

friends, most of the porcelain I have noticed is of a date much more

ancient

than those bottles which have been found from time to time in Egyptian

tombs. I

have in my possession examples of these bottles found in China

generally in

doctors' shops identical in form, no doubt of the same age, and

having the

same inscriptions on them as those found in Egypt, and from all that I

can

learn they are not older than the Ming dynasty. An article on the

proceedings

of the "China branch of the Royal Asiatic Society," by W. H.

Medhurst, Esq., her Majesty's Consul at Foo-chow-foo, proves this most

satisfactorily, by showing that the inscriptions are portions of

poetical

stanzas by standard and celebrated Chinese authors who flourished about

that

time. As the concluding part of Mr. Medhurst's paper bears somewhat

upon the

matters I have been discussing, I shall take the liberty of introducing

it in

this place. "I have not been able to ascertain

anything

equally satisfactory regarding the discovery of porcelain. The earliest

notice

of its existence, as a ware, that I can find, occurs in a poem by one

Tsow-yang, a worthy who lived in the reign of Wan-te, of the Han

dynasty,

175-151 B.C.; but it is only casually mentioned as 'green porcelain.' Pan-yŏ, a writer of the reign of Tae-che,

of the Tsin

dynasty, A.D. 260-268, speaks of 'pouring wine into many-coloured

porcelain

cups;' and the biography of Ho-chow, an eminent character of the Suy

dynasty,

A.D. 608-622, tells us that its hero restored the art, then long lost

in China,

of making Lew-le, a sort of vitreous glaze, by constructing it

of porcelain.

Writers of the Tang and Sung dynasties mention it oftener, its use

having

perhaps become more general in their time. I should, therefore, infer

that the

manufacture was not known previously to the first-mentioned date, as it

is not

probable that so useful and valuable a ware would have escaped

historical or

casual notice, had it existed in sufficient quantity to allow of its

being

applied to the manufacture of common bottles. "I need only add that I have trusted in no

instance to hearsay evidence in bringing forward the information I have

herein

collected, but have carefully examined each authority myself previously

to

recording it upon paper; and perhaps it may not be out of place for me

to

remark in conclusion, that my teacher scouts the idea of associating

these

bottles with the Pharaonic epoch as utterly visionary and absurd, it

being

impossible, he says, that vessels composed of a ware universally

acknowledged

to be no older than the Han dynasty, and inscribed with quotations from

verses

that cannot, if the history of Chinese poetry be true, have been

written before

the Tang dynasty, could have found their way into tombs which were

contemporary

with the earliest recorded events of Chinese chronology. He is, on the

contrary, decidedly of opinion that the bottles in question were

manufactured

during the Ming dynasty."

|